Live

- Indian women’s unlimited capabilities, potential established globally: Annapurna Devi at UN

- MP govt to present economic survey, discussion on Governor's address to follow

- Land grabbing: Case filed against Sam Pitroda

- Centre selects Renuka Yallamma temple under 'PRASHAD' scheme; Bommai thanks PM Modi

- Police Commissioner distributes 86 e-autos to women

- Donald Trump Announces Purchase of New Tesla, Supports Musk Amid Tesla Boycott

- Bommai seeks thorough probe into Ranya Rao case

- BJP opposes Greater Bengaluru Bill

- 3 dead, 24 injured as NLU Jodhpur students’ bus overturns in Nagaur

- Armenian Foreign Minister thanks EAM Jaishankar for warm welcome

Just In

During my travels in South East Asia, the hotels I stayed in were often peopled mostly by tourists from other parts of Asia.

During my travels in South East Asia, the hotels I stayed in were often peopled mostly by tourists from other parts of Asia. This, however, is a relatively new trend, somewhat offsetting the domination of the western tourist for very many decades post decolonisation. Among westerners, the English and European tourists have been the most important as far as Asian countries are concerned.

The Americans are not as fond of travelling, despite their nation’s wealth. I suspect that there may be two reasons for this. First, the Americans haven’t enjoyed a rich colonial history in the same way as the Europeans – even if they did occupy the Philippines and Japan for an extended period of time. When a territory is colonised, it becomes in a sense part of the property of the colonising nation, and its people develop an interest and relationship with the subject nation that carries on long after that nation achieves independence. For this reason, the Dutch are more likely to visit Indonesia, the Spanish might prefer to holiday in Argentina, and the British come to tour India. I speak here of the Spanish, the Dutch and the English as ‘groups’ – an individual may, of course, have his own individual preferences about the countries he would wish to visit, though these choices, too, are often influenced by historical context. Apart from the absence of a colonial past, I suspect that the Americans are somewhat insular, and too immersed in their own large country. They can travel quite a lot within the United States, and if they really want a change they are likely to confine their explorations to the Caribbean or Latin America.

As a result of western economic power, even that of the less affluent sections of the populace, areas have sprung up in important cities all over Asia that are especially popular among western tourists. Some cater to the lower end of the market, namely backpackers; others to high-paying tourists. In Delhi, for instance, you have Khan Market for the upmarket westerner and Paharganj for the backpacker, in Bangkok you have Khao San for the backpacker and Sukhumvit for the better heeled, and so on and forth. Here in Phnom Penh I found a riverside park near the Sisowath Quay, which lies beside the junction of the Mekong and Tonle Sap River, to be popular with western tourists. Enthusiastic joggers can be found here in the mornings. In the evenings the place lit up with music and meals on offer.

* * *

An array of shops not far from the quay is popular with tourists. Although the location is generally upmarket, it does not entirely exclude the backpacker, being a mid-level kind of place. The wide road that runs alongside the shops contributes to the upmarket feel, as does the attraction of the river nearby. I found the usual travel agents, restaurants offering a variety of cuisine from Italian to sushi, and numerous hotels that advertised themselves as luxury boutique guesthouses.

One of these hotels was all of twelve feet wide, but climbed up to seven floors! The Khmer Royal Hotel was another so-called boutique hotel and still hung a large cloth banner outside saying ‘Welcome Mr Obama!’ long after the President’s visit in 2012, perhaps with a view to luring patriotic American tourists. Some hotels, such as the Bougainvillier Hotel, were genuinely boutique, with stylish exteriors and rooms leading out into traditional French balconies facing the riverside.

* * *

I booked an afternoon tour with V Silk Travels and Tours, one of several travel agencies at the quay. During the course of three hours, the driver took me to several notable places in the city, such as the famous Silver Pagoda and the Russian Market. The pagoda had exquisite carving, and in the vihara inside there were priceless works of art, including statues of Buddha made of gold with embedded jewels. The most priceless of these treasures is a small green crystal Buddha. The so-called Russian Market was run down and a disappointment. With nothing remotely Russian about either the ambience or the merchandise, it was an ordinary market for cheap goods. We passed an impressive new building, built by the Chinese, that housed the Prime Minister’s offices. The most important part of the tour was a visit to the Genocide Museum, and the Killing Fields that adjoined the commemorative stupa at Choeung Ek.

* * *

Choeung Ek was around seventeen kilometres outside the capital. We reached there after a forty-minute drive. A large group of tourists was already present.

A walking track complete with small wooden signs indicated the manner in which the genocide had been carried out. Gadgets fixed to your ear contained western-style sound recordings in different languages that explained what had transpired. So you walked along the path listening to the tape. Of course, the creators of the recording couldn’t possibly know how long you would stand at a particular spot, so you had to use your head and work it out. In a way it was much like visiting the scene of a crime that has been marked out by a crime investigator – but this was, of course, no ordinary killing but a genocide in which forensics has already taken away all (or almost all) of the physical evidence.

The single terrible exception to the absence of physical evidence of what had happened was a tower in the centre, where human skulls were mounted in multiple layers. The tower itself has glass sides and is built like a commemorative Buddhist stupa. The skulls inside number five thousand, representing a small fraction of the deaths that took place only a few decades ago. Although the design is avowedly that of a stupa, it looks like a truly bizarre piece of modern art – except that the skulls are real and not man-made.

The area itself was previously an orchard. With its outdoorsy countryside feel, it would be a place to enjoy a picnic if it not for its terrible history. The sun was shining brightly. Apart from the tall skull-filled monument standing in the centre and the mechanised recordings providing information in the detached, emotionless tones of a voice-over professional, it could have been any other part of the countryside. Nature is such a silent, peaceful witness to the violence of man.

* * *

After forty-five minutes, we drove back to town to visit the Tuol Sleng Genocidal Museum. Scores of photographs of those who had been kept in custody, tortured and ultimately killed had been mounted on the walls. Anonymous faces of young boys and girls, as well as older men and women stared at the visitor, their faces displaying little awareness of the terrible fate that would soon befall them. Some prisoners were depicted in a terrible state. The violence carried out paid no heed to the youth or age of the victim. I saw a large photograph of an emaciated and naked aged man and another of a naked young woman. The Khmer Rouge were as brutal as they came. More affected than I had imagined possible, I sat on the steps for a long while, overwhelmed by this evidence of humankind’s brutality and stupidity.

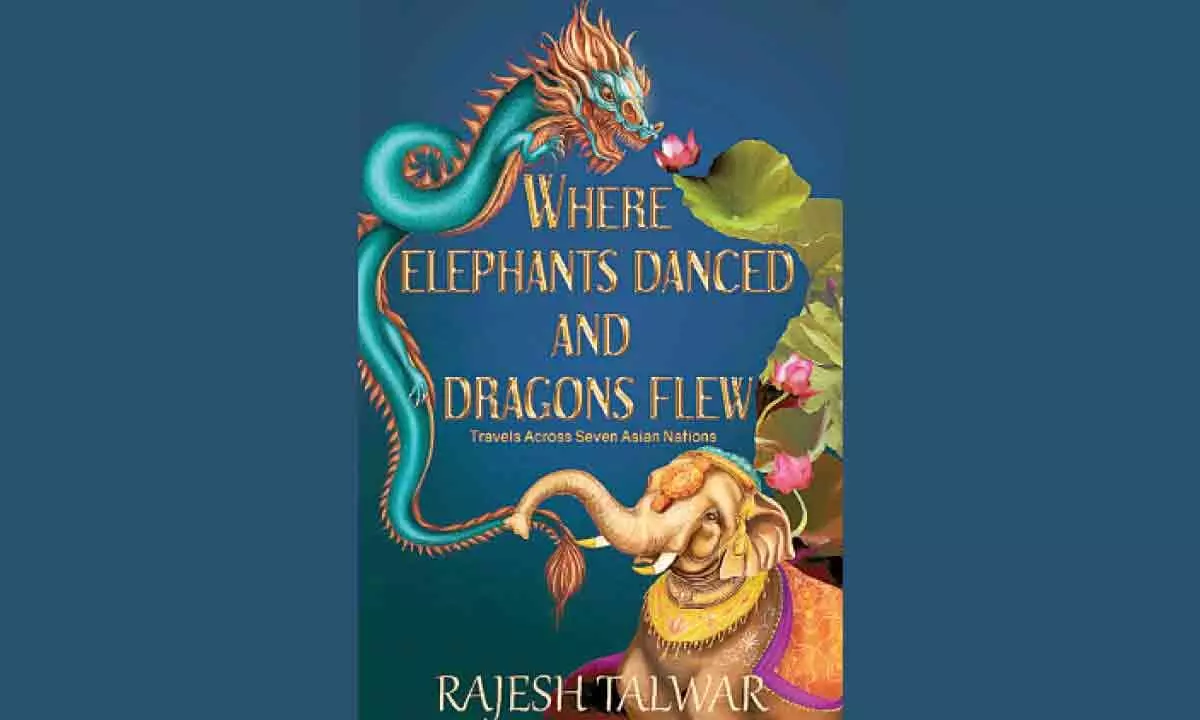

(This excerpt from ‘Where Elephants Danced and Dragons Flew’, written by Rajesh Talwar, has

been published with permission from Bridging Borders, Rs 206)

© 2025 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com