Live

- Anna University rape case: BJP says accused belongs to DMK student wing

- 'Dooradarshini' Brings the 90s to Life with a Nostalgic Love Story

- BJP Accuses Congress of Anti-India Politics After Distorted Map Displayed at CWC Venue

- ISL: Fluent Odisha face depleted Mohammedan in search of top four spot

- Afghanistan won't tolerate any aggression, warns Kabul after Pakistani airstrikes that killed 46

- India a global leader in disaster warning systems: Jitendra Singh

- India vs Australia 4th Test Day 1: Bumrah Shines as Australia Holds the Advantage at MCG

- Adani's Vizhinjam port welcomes 100th vessel within 6 months of operations

- Squid Game Season 2 Now Streaming on Netflix: Cast, Plot, and Release Details

- Gottipati Ravi Kumar Criticizes YS Jagan Mohan Reddy’s Power Sector “Tughlaq Acts”

Just In

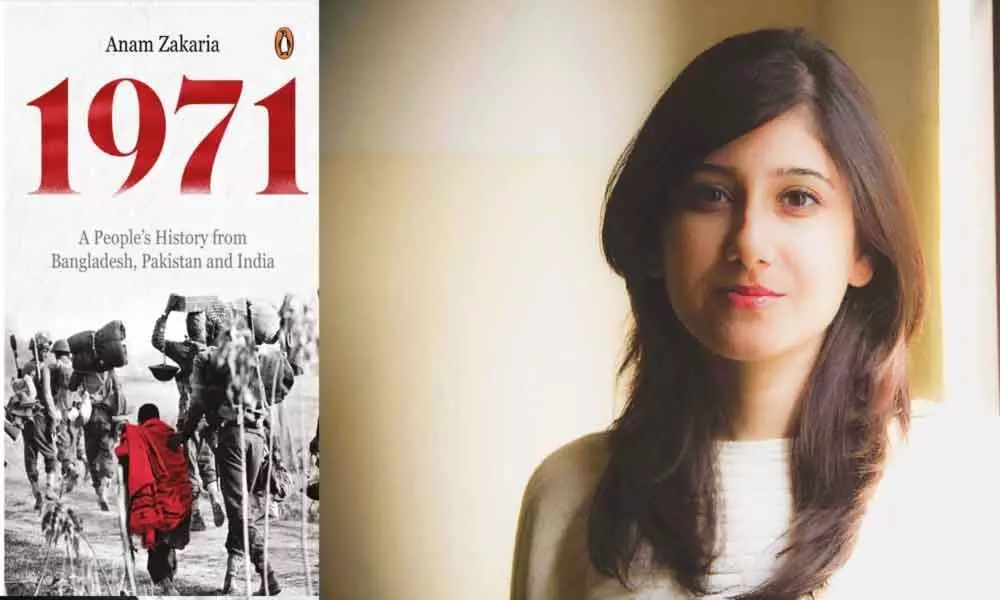

In her book, Anam Zakaria navigates the widely varied terrain that is 1971, across Pakistan, Bangladesh and India, and the three distinct State narratives.

In her book, Anam Zakaria navigates the widely varied terrain that is 1971, across Pakistan, Bangladesh and India, and the three distinct State narratives. The extract looks into the situation that led to changed sentiments of the then East Pakistani citizens towards West Pakistan

The peasant and the aspirant middle class shared a common dream: an end to British and Kolkata-Hindu domination in jobs

and trade. This was not an issue of Hindu or Muslim identity but of economics. When Bengali Muslims voted overwhelmingly for the Muslim League in 1946, they were not voting for Pakistan but for a life free from zamindary rule and famines. Bengali Muslims were mostly peasants, sharing many traditions with their Hindu and Buddhist counterparts. But most of the landlords were Hindus.

Partition and the creation of Pakistan then symbolized emancipation. Opportunities and progress and a vote for Pakistan meant a stand against economic oppression. In fact, 1 would learn that many of the East Pakistani Partition survivors, who were pro—Muslim League in 1947, found it harder to let go of their belief in Pakistan in the post-Partition years. A number of people whose parents had supported the creation of Pakistan told me that their mothers and fathers continued to believe in the idea of Pakistan until 1971, even though the younger generations had become disgruntled earlier. It was only when the military operation was launched in March 1971 that these supporters became disillusioned, accepting that separation was the only solution.

This first generation found it harder to let go, particularly because they had helped create the country that was now depriving them of the very rights they had fought for. It was a difficult truth to digest, but one that the military operation and the resulting widespread violence had finally necessitated. Today, however, recognizing this support for the League is a complicated affair. Bangladesh's liberation war history is premised on the struggle against West Pakistani hegemony; the time the two nations spent together as East and West Pakistan is remembered as a dark era.

To acknowledge that the Pakistani movement enjoyed support in Bengal makes it difficult to explain the rise of Bengali nationalism soon after the creation of Pakistan. These perceived contradictions in what is projected as a linear and simple history of Bangladesh complicates the past. Partition as a result has come to be hushed and silenced.

While I found only a few people willing to talk to me about 1947, I managed to set up a meeting with Serajul Chowdhury, a Partition survivor and prominent Bangladeshi academic whom I met at Dhaka

University in 2017, where he serves as professor emeritus. Our conversation began with the importance of the location of our interview. Pointing towards a large ground from the window in his office, he said, "Do you know that in 1971, this is where the Punjabis surrendered? This is also where jinnah gave his 1948 speech in which he declared that Urdu, and only Urdu, will be the state language of Pakistan. Many would argue that the speech itself (which I will delve into in more detail in the next chapter) became the catalyst for the separation in 1971. It was poignant that the speech, which gave rise to dissent in East Pakistan, was offered in the same place—Ramna Race Course ground, now known as Suhrawardy Udyan — where Pakistan signed the historic surrender document that marked the formation of East Pakistan as the new nation of Bangladesh. The birth and culmination of the Bangladeshi movement was embedded in this very site.

It is also noteworthy that when Serajul Chowdhury spoke of the surrender, he referred to the surrender of the Punjabis rather than Pakistan as a state. It can be argued that it was Punjabi hegemony that led to resentment in East Pakistan. The army and bureaucracy are both dominated by Punjabis. Also, it was Punjab that was at the forefront of recognizing Urdu as the state language.

In fact, even today, while regional languages are taught across Pakistani provinces for instance, Sindhi in Sindh, Pushto in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, etc.), Punjabi is not taught as a subject in schools in Punjab. Urdu remains the medium of instruction across the province, justified in the name of 'national language'. A child from a school in Lahore had told me that her school fined students Rs 50 if they were found speaking Punjabi.

In 2016, one of the largest private educational institutions in Pakistan, Beaconhouse School System, issued a discipline policy forbidding students from speaking Punjabi, referring to it as a foul language. Punjab has constantly tried to show that it is separate from India; in the process of constructing this independent Pakistani identity, it has found it necessary to shun itself of its Punjabiness, particularly of any connection to the Indian part of Punjab. In this national project,the regional culture is imagined to be subservient to the broader (national culture', represented by Urdu. Anyone who challenges this hierarchy is seen to be challenging national identity, like the Bengalis who immediately after the birth of Pakistan demanded that Bengali-spoken by more than 50 per cent of the population be recognized as the state language. When the army, also dominated by Punjabis, launched an operation in March 1971 to curb Bengali nationalism, it was once again perceived as Punjabi exploitation and oppression of the people of East Pakistan.

Soon after the creation of Pakistan, the state had begun to accept Punjab as the true Pakistan. Bengalis, who had helped the Muslim League secure enough votes and support for the country, were cornered and their patriotism was constantly in question.

Our location was also significant because it was in this area that the Muslim League had been established in 1906. "There was an outhouse here that belonged to the Nawab family. That was where the Muslim Conference took place and they decided to form the Muslim League," Serajul told me.

- Extract from Publisher

Penguin Random House

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com