Just In

‘Sundara Kaanda’ is a metaphor between Baabi and Hanuman: Ikshvaku

‘Sundara Kaanda’ is a metaphor between Baabi and Hanuman: Ikshvaku

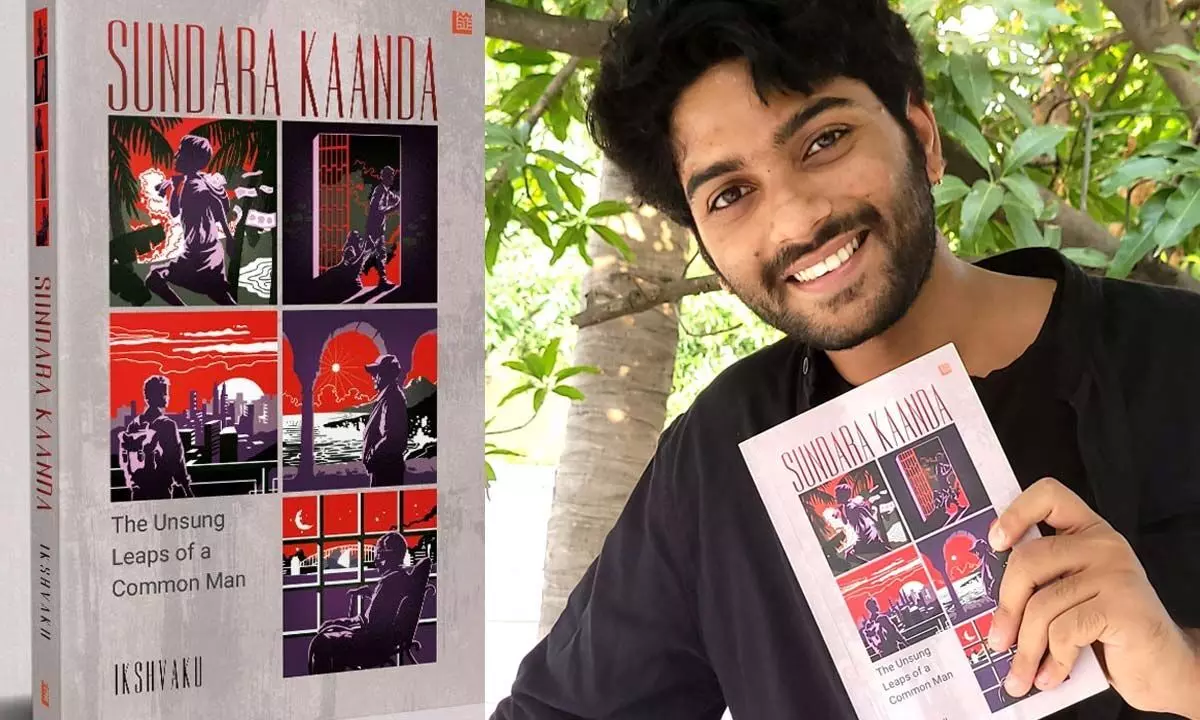

Ikshvaku, the author of the book ‘Sundara Kaanda: The Unsung Leaps of a Common Man’, gives an account of his thought process while writing the book in this interview.

Ikshvaku, the author of the book ‘Sundara Kaanda: The Unsung Leaps of a Common Man’, gives an account of his thought process while writing the book in this interview. The book is about the gripping and adventurous story of Baabi, a common boy living in Vakkalanka, Andhra Pradesh, and how losing 15 Rupees turns his life upside down from then on. He compares Baabi’s story to that of Hanuman, drawing a metaphor of how mythological tales are very much related to real life experiences.

What inclined you to be an author, and how did this story come to you?

I consider myself an honest amateur and a descendent of a lineage - cherished by many a mural in India’s history, out of my penchant to play with words. Therefore, having a paramount passion for storytelling, I needed to choose a channel that I could contaminate tolerably, as opposed to substantially, the victim of which has been the paperback.

It was on a leisurely Wednesday afternoon when I was arrogantly appreciative of my expertise to bunk school that my grandfather (the protagonist of the story) began narrating to me an account of how skipping school had cost him, the substance of which inspired Sundara Kaanda.

How did you get the idea of drawing a metaphor between Baabi and Hanuman?

Growing up in a household that principally functioned, much to my sweet fortune, on recitals of the two great Indian epics, I have developed a rather distinctive property of producing metaphorical undertones for any story. It resonates better with its readership. That is primarily what I had done with Baabi and Hanuman.

The book contains a lot of historical and cultural references. How much research was put into it for the story to be what it is now?

About the incidents that concern the cultural and indigenous practices, the process of constant corroborations, rebuttals, and confirmations was nearly an 18-month expedition into the depths of my grandfather’s memory and mind. Rummaging through his old journals and letters was at times an intensely laborious exercise as well as a remarkably educative one too.

Why Ikshvaku as your name?

One would expect that a pen name is usually forged out of some notable history in the author’s life. But I can divulge to whoever is trying to solve my name’s newfound riddle that I chose it for the kick of having a direct reference to a character I dearly admire (Lord Ram) and also to elicit an interest that encourages one to visit the source of it, ultimately taking them to the stories of India.

What part of the book did you enjoy writing about the most and why?

I enjoyed the part that demanded the best of my abilities as a writer to contain within the folds of my penmanship the disastrous emotions it had to offer, which is clearly the climax - Kaasi.

Do you have a favourite ‘leap’ that Baabi had to take but got deleted during proofreading?

Although I was compelled to redact and edit some portions of the epic tale, I ensured that any momentous ‘leaps’ did not have the misfortune of being pruned; but certainly, some segments could not make it to the final draft, which is maybe for the best.

What is the main message that you wanted your readers to get through your book? and more importantly what is the most vital lesson you have learnt through your journey of writing and publishing this book?

The aim of my book has never been social instruction whatsoever. However, in light of what I learnt, it is that such a story is native to every home, only locked away in the unexplored psyches of our fathers and mothers, and by asking them their history, they give you your age, which is vital, and you give them your youth, which is noble.

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com