The Creation Of The IPL

When the legendary Arthur Morris, key member of Don Bradman's invincible team of the 1940s, was asked what he got out of playing cricket, his answer was startling.

When the legendary Arthur Morris, key member of Don Bradman's invincible team of the 1940s, was asked what he got out of playing cricket, his answer was startling. Morris negotiated the question with a single-word retort: 'Poverty'. With the onset of a cricketing revolution courtesy of the Indian Premier League, contemporary cricketers will have a radically different answer to a similar question. Most, it can be conjectured, will suggest with a welcome smile, "We became millionaires."

However, the process of them becoming millionaires wasn't an easy one and the credit has to go to Lalit Modi for transforming the sport forever.

It was around 4 p.m. in the afternoon on 18 April 2008 and I was right outside the Chinnaswamy Stadium in Bengaluru trying to gauge the mood of the crowd that was starting to build up. I had been a sceptic and was not sure if anything except nationalism worked in Indian cricket. We in India, I have always argued, don't really consume cricket. Rather, we consume spectacle. We don't watch the Ranji Trophy, the national championship for cricket in India featuring the best of domestic talent. We don't watch the Duleep Trophy, yet another premier domestic tournament. We only watched the Indian national team play and that's where the scepticism was coming from. Will Modi's brainchild, pitching one city against another and involving the world's best players, capture Indian public imagination?

"You weren't the only sceptic," said a senior BCCI functionary when I mentioned my doubts to him while writing this. "You should have seen Lalit on the day IPL started. He was putting on a show but from inside was a nervous wreck. His career was at stake. If the start wasn't up to the mark and if people did not warm up to the concept, his career in sports administration would come to an end," said the source. "In fact, many within the BCCI also wanted him to fail. He had ruffled a lot of feathers in the way he had worked the last few months and you can't do so in an institution like the BCCI. You end up making enemies if you do and Lalit would have to pay the price if the IPL did not take off," he concluded.

Frankly, when Lalit had set off planning the IPL, all he had in front of him was case studies of a few American and British leagues. He had extensively studied how the NFL and the MLB worked in the US and planned to take the best practices from each to create something unique for the Indian market. He had partnered with IMG in doing so and in a meeting held in July 2007 during Wimbledon, first outlined some of his thoughts on the IPL to his colleagues in IMG. With the ZEE network led by Subhas Chandra already on the start line with the launch of the Indian Cricket League in April 2007, Modi was faced with stiff competition in trying to accomplish his vision. While he was seeking an alternate model that worked in India, he knew that Indians had little or no regard for domestic cricket.

He also knew that for a league like the IPL to work in India, matches had to be played prime time and he had to rope in the best players globally. The problem was the players were already overworked. Calls of a burn out were rife and to expect them to play for 2 more months non-stop was unrealistic unless Modi was able to sweeten the deal by paying them monies they had never earned before. He also had to work on franchise owners and the first thing he had to do was convince franchise owners of what they owned.

A franchise-based league was alien to the Indian market and in the absence of a physical asset a lot of the owners were not convinced to start with. "Some of them asked Lalit what they were owning. They would own no physical stadium unlike some of the established football clubs in India. Nor will they own something like what the state cricket associations did. So while he expected them to spend 60 million dollars for a franchise, he needed to explain to them what they were getting in return for the money spent and how they were supposed to recover the money. I have to tell you it wasn't easy for him to get the high and mighty from around the country to buy into the concept," said a former BCCI President closely involved at the time.

In the absence of physical ownership, franchise owners needed to buy into an idea. They had to buy into Lalit Modi. They had to start from the premise that the tournament would take off. Only if they believed in it could they agree that they would make money from ticket sales, merchandise, hospitality and of course broadcast rights. Modi, an industrial magnate in his own right, had to use all his personal connections to get the franchises sold off to India's best. He also had to get a broadcaster on board and it was more difficult than was envisaged. For a T-20 competition, no broadcaster was willing to risk everything.

The format had not yet taken off in India and the duration of the games meant far less time than a 50-over match to monetise advertisement spots. Pitted against soaps and prime time serials, it was a risk no broadcaster could afford. While some suggested a revenue share model, Lalit was fundamentally opposed to such a concept. No sports league in the world could work on a revenue share principle and the broadcaster had to have skin in the game and believe in the concept if they really wanted to deep dive into it.

Getting a broadcaster was key to be able to demonstrate to franchise owners that over a period of time they will start to earn significant profits and there was much more to the league than just vanity. Lalit was also playing on a new Indian mindset where the city had replaced the state as the primary loyalty for the youth. In my case, for example, I am an Indian first and then I am from Kolkata. However, I would always say Kolkata ahead of West Bengal and there was no cricket tournament that had been organised along these lines.

The Ranji Trophy was played between states and other tournaments were zonal in nature. To get cities to play each other would be an attempt at creating a very different kind of loyalty than before and mark a departure from established practice. Would it work? No one really knew. Was it worth a try? Lalit Modi believed it indeed was.

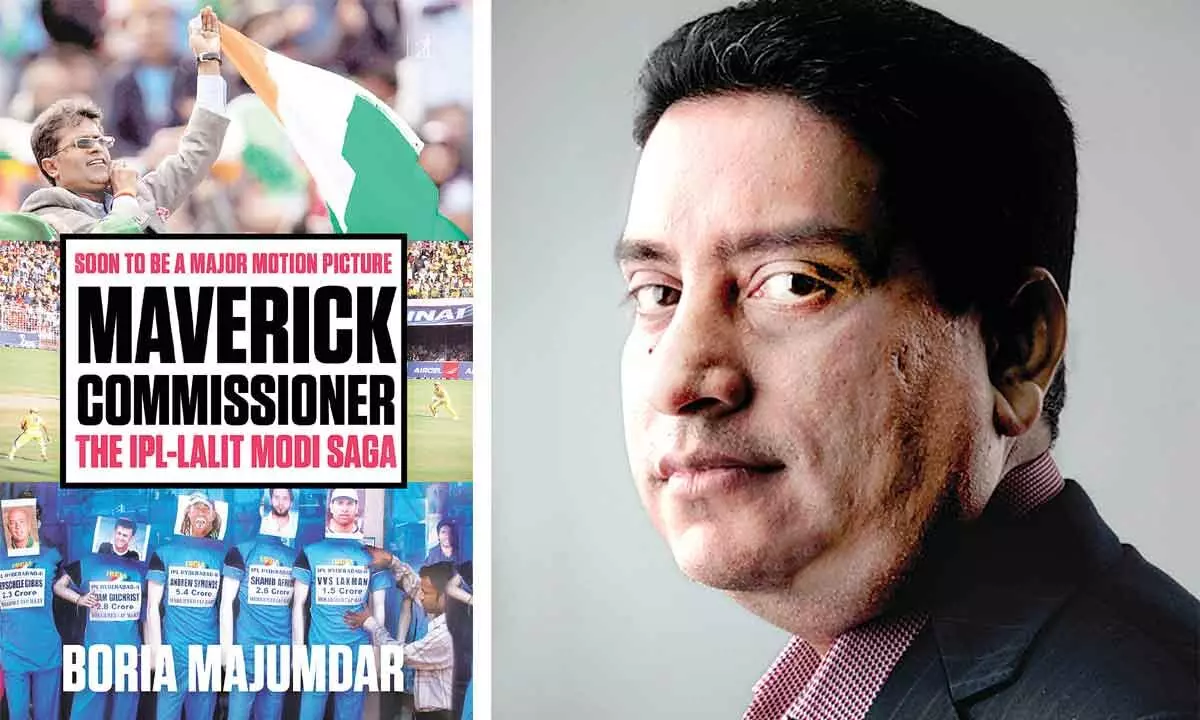

(Excerpted with permission from 'Maverick Commissioner: The IPL-Lalit Modi Saga' by Boria Majumdar Rs 699, 240PP, published by Simon and Schuster India)