Live

- Gujarat Air Force Association organises annual memorial lecture on national security

- RJD MP urges Nitish Kumar to demand special package for Bihar during Delhi visit

- Indian Navy's training ships undertake professional exchanges in Cambodia

- PM Modi’s advice during ‘Pariksha Pe Charcha’ helped me overcome exam fear: 10th grader Ananya Batham

- Odisha: Key suspect in murder case surrenders in Bhubaneswar

- Gujarat: Man pressures woman for religious conversion in Vadodara

- Additional RPF deployed to facilitate Maha Kumbh devotees: Central Railway after Delhi stampede

- IPL 2025: KKR and RCB to play tournament opener at Eden Gardens on March 22

- Tejas Dhingra retains national championship title at NEC Show Jumping 2024-25

- Skydiving festival kicks off in Jamshedpur, highlights Jharkhand’s tourism potential

Just In

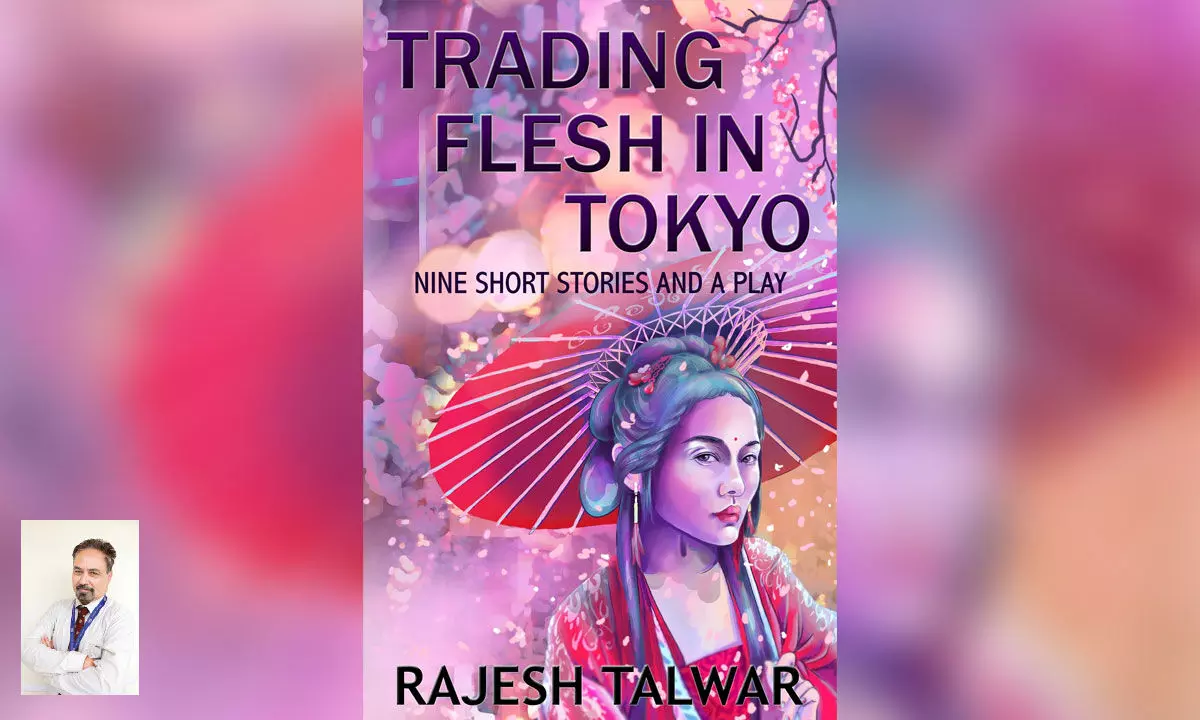

This is a small collection of nine delightful stories and a play. The stories deal with love, poverty, crime, passion and various troubling social issues. The characters in the play are powerful non-humans who are familiar to all of us. In ‘Trading Flesh in Tokyo’, an ageing American-Indian publishing executive falls in love with a young Japanese girl, but there are weighty issues that need to be resolved

Japan was a mystery to me. It was easy enough to think up a few questions to ask her, as we sat down for coffee. It transpired that Katsui – for that was her name – taught English to Japanese students at a nearby language institute. She lived in Yokohama itself, sharing a first floor with her grandmother. Her father, a widower, lived on the ground floor of the house. She didn’t earn very much, for it was a small private college where she gave lessons. She was a different kind of Japanese in that she valued time over money. Being from New Orleans, which is a trifle laid back compared to, say, New York, this was a quality that I appreciated. I had no time, which is the correct if somewhat ironical expression, for the super-busy Japanese company executives who sit down to have a beer and simultaneously take out a notepad, a laptop, and two different mobile phones to do some work!

Katsui had backpacked all over Asia and Europe, although she had never been to the States. We talked about our different experiences in a few Asian cities we had both been to, including Ahmedabad, from where my family originates. The five minutes agreed upon turned out to be an hour, at the end of which we exchanged phone numbers and agreed to meet sometime later in the week. When I called a few days later, she suggested we go out for sushi served on a revolving platform in front of the diners. It was something I had yet to sample, and she agreed to help me understand the finer points of eating in such an establishment.

The following week she invited me for what turned out to be a fabulous meal at her favourite Chinese restaurant: Yokohama has a bustling Chinatown, and a large Chinese community. The week after, I invited her for dinner at an expensive Italian restaurant inside one of the high-rise buildings that overlook the bay, just besides the Landmark Tower, the tallest building in Japan.

One thing led to another, and soon we were seeing each other every second day. I was afraid she wouldn’t allow me to pay as I often as I would have liked, but I need not have worried. I paid the bill on most occasions when we ate out or went to a performance, and she happily allowed me to do so. Several classy restaurants were located near the oceanfront and beside the canal that ran through part of the city. There was one in particular that we both loved, which served continental fare and had lovely jazz music played by energetic youngsters who jumped about as they sang – something I had not expected in this country. I began to look forward to delicious food at dinners that also combined it with a musical performance and a view of the bay.

I’m not sure if I qualify to be called a much-married man. I’ve been married twice, and both times it ended in disaster. My first wife, a white American blonde with an hour-glass figure, was money mad – the greedy, materialistic bitch. No matter how much I earned, it wasn’t enough for her. Within two years of our marriage, she decided that for a woman with her looks and figure my earnings weren’t enough. She dumped me, and ran off with a Texan with oil interests. My second wife, whom I married five years later, after the wounds from the first had healed, was of Gujarati Indian stock, like myself. Nevertheless, she cheated on me with a friend less than two years into our marriage. It wasn’t a one-nighter; she’d been having it off with him for a period of months before I found out. I’m not the forgiving kind, and it was the end. After the second divorce, I thought I was finished with marriage, though not with women. I had stuck to this resolve and been single for the past fifteen years.

And yet, after having known Katsui for barely three months, I started to entertain thoughts of a third marriage. I had met her only half a dozen times, and had experienced no physical intimacy with her beyond the occasional hug and kiss, but I knew that she was the woman I wanted to be with for the rest of my life. She was younger than me by almost two decades, so I didn’t think I had much of a chance, but one evening after a late candlelit dinner at one of the restaurants that had a view of the Bay, with the soft notes of a violin playing in the background, I proposed to her.

She didn’t seem at all surprised. And, for my part, I was both surprised and encouraged that she took my proposition in her stride.

She didn’t respond to me at once, but sat quietly, her eyes downcast, and apparently concentrating on her miso soup, but I knew she was tossing the idea around in her mind. After we had finished dessert, which was a greenish Japanese ice cream – her favourite, and one that I pretended to enjoy, she said softly: ‘I like you very much, Mohan. Age is not an issue with me, if that is your concern. I could certainly consider marriage with you, but I have a condition.’

A condition?! My heart leaped at her statement. Surely I could meet with a simple condition. As someone used to negotiations, I noted with guarded optimism that she had used the singular.

‘You have to eat whatever I allow,’ she said, ‘and not eat what I forbid you. Is that too difficult for you?’

Seeing the nonplussed expression on my face, she went on to explain that American men ate all the wrong things, and led very unhealthy lives in general.

‘We have an average life expectancy of eighty-two in Japan,’ she said, ‘which is far higher than what you enjoy in your country. I would like you to live long and to be healthy. Even if you were not my husband, but more so if you were.’ She pursed her lips, and then made a face. ‘The way you are going now, you won’t live long. You may be of Indian origin, but have very unhealthy eating habits – like most Americans. All that fried stuff: eggs, sausages, bacon. My God! I’ve seen what you have for breakfast. You’ll have to give up all of that.’ I said that I was happy to accept her condition.

(Excerpted with permission from ‘Trading Flesh In Tokyo - Nine Short Stories And A Play’ by Rajesh Talwar, publisher Bridging Borders, price: Rs 269)

© 2025 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com