Vedas In the Jungles

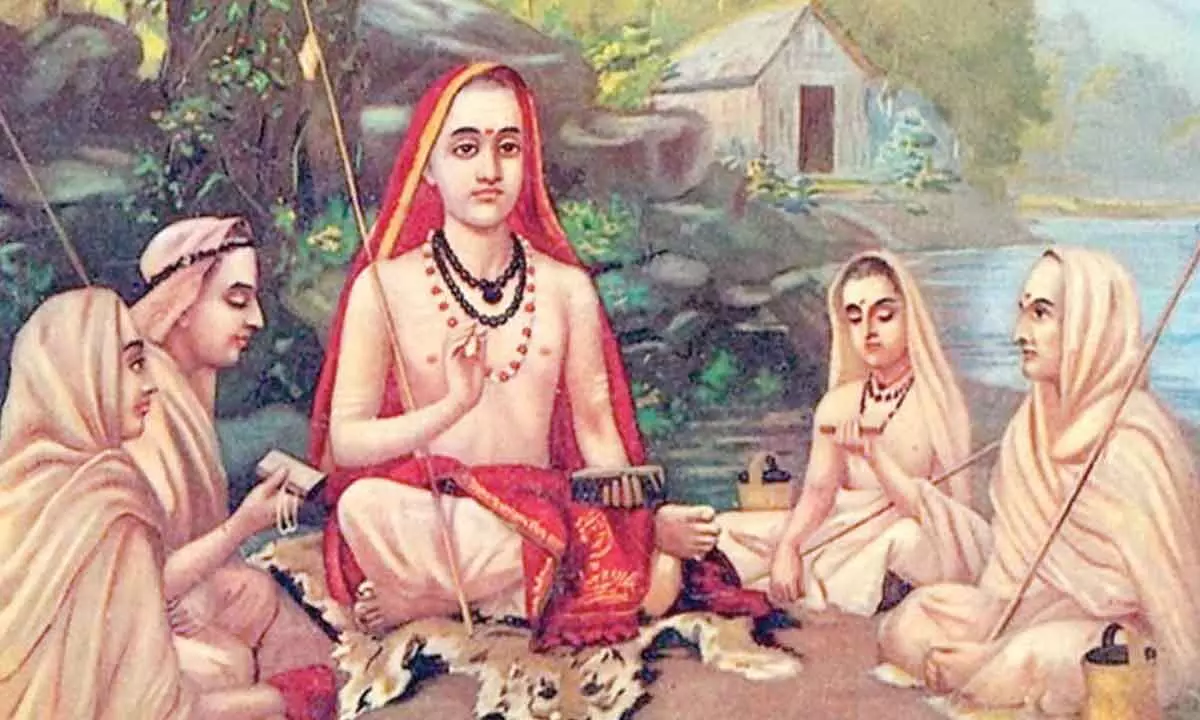

Indian society was too complex to be described in simplistic terms. The practice of study of Vedas in the forests and the interaction between the sages and the hunter-gatherers is one such. The people in Vedic society stayed in towns or villages and performed rituals such as yagnas and supported society, but as they grew old, they retreated to nearby forests and spent time in contemplation. During such tapas, they had revelations of eternal truths which came to be called the Upanishads

Indian society was too complex to be described in simplistic terms. The practice of study of Vedas in the forests and the interaction between the sages and the hunter-gatherers is one such. The people in Vedic society stayed in towns or villages and performed rituals such as yagnas and supported society, but as they grew old, they retreated to nearby forests and spent time in contemplation. During such tapas, they had revelations of eternal truths which came to be called the Upanishads.

These were not the only people in the forests. There were also the forest dwellers, such as the hunter-gatherers who brought forest produce such as fruits, honey and such other things needed by these retreaters. Cultural exchange was inevitable. Vedic literature shows the close relationship between the sages and the tribals. Sage Matanga in the Ramayana is a prominent example of a tribal attaining the status of a great sage. During his stay in the jungles, Rama visits the ashram of the sage to see Shabari, the disciple of sage Matanga. Shabari describes the ascetic powers of Matanga, who had attained heaven by the time Rama visited the place. Shabari is also a tribal woman who had performed austerities and attained the status of a sage.

The Varaha Purana gives some significant stories. In one such story, a hunter has a discussion with a sage on the nature of non-violence. It appears that the tribals or hunters who also followed the austerities of brahmins were called dharma-vyadha in those days. Such dharma vyadha approaches a sage (Ch 8) and offers his daughter to the son of the sage. The sage knows the good nature of the girl and accepts her as daughter-in-law. However, on one occasion, his wife shows an air of superiority and blames the daughter-in-law calling her the daughter of a hunter. In that context there is a discussion between the hunter and the sage about the nature of non-violence, ahimsa. The hunter goes to the house of the sage at lunch time. Lunch is offered to him, but he finds that the so-called lifeless cereals, pulses and vegetables were all products of some violence to countless small living beings. Each grain has a life force and is equal to a bird or an animal. The sage realizes his mistake and apologizes to the hunter.

In another story from the same purana (Chs 37, 38) a hunter does tapas and attains the status of a sage. He even hosts the eminent sage Durvasa, satisfying him in all the tests about ascetic powers. Durvasa is pleased and hence gives Vedas and the knowledge of Supreme, to the erstwhile hunter, saying that his body is now purified by austerities. We may believe or dismiss ascetic powers, but the message is clear that a hunter could attain the status of a sage. We also have the famous story of Valmiki himself who, by sheer tapas, became a sage.

The Mahabharata gives the story of another dharma-vyadha, a meat seller, who makes a living by selling meat. But he was conversant with dharma. A supercilious brahmin, proud of his learning, was asked to go to the hunter and know the intricacies of dharma. Social equality and spiritual equality were clearly balanced in such episodes.

The forest retreats produced texts known as Aranyakam, meaning that they were studied in aranyam, a forest, and they were important portions of the Vedas. They were also the predecessors for the Upanishads, which are known as Vedanta, the final message of Vedas. On the sociological side, the retreats inevitably produced a close relation between the practitioners of the Vedas and those living in the forests. This fact is forgotten because historians missed the life sketches in the puranas. The simplistic explanation of some historians that the invaders drove the original inhabitants to jungles looks ridiculous if we see the harmonious integration of the forest dwellers in the Vedic culture.

The tribals in the forest were an important contingent in the royal army, as we see in the episode of Guha in the Ramayana. Will our historians study these and think of telling correct history?

(The writer is a former DGP, Andhra Pradesh)