Combating Challenges of Corruption – II

Good governance has, for several decades, figured high on the agenda of the national and state governments in our country.

Good governance has, for several decades, figured high on the agenda of the national and state governments in our country.

Corruption, nepotism, leakages and incompetence are among the many scourges that have tainted the image of, and adversely affected, the performance of the administrations at various levels. As always, the worst sufferers have been the public at large – especially the poor, the excluded and the underprivileged sections thereof.

It is not my intention here to discuss different aspects of the malaise of corruption – its causes, the common forms in which it presents itself, or the most effective methods of containing it. The point I wish to make is that in its essential form, it is the reflection of generic weaknesses germane to the socio-economic structure and the set of rewards/punishments established by that structure.

In the context of understanding graft in its different forms, it is pertinent to refer to what is popularly known as the 'mamool' or the 'hafta' systems prevalent in many parts of India, particularly in the urban areas. Fixed periodical amounts are paid as "protection money" by those owning or operating small commercial establishments in a given area to the 'local toughie' in exchange for an assurance that protection will be guaranteed to the shopkeeper from law enforcing agencies.Those who demand, and receive, such payments often belong to a large and organized 'mafia.' In a manner of speaking, the practice also speaks of the plethora of legislations and attendant enforcement agencies that a business person has to contend with.

On account of the inability to handle both work and the need for compliance, refuge is sought in the periodical payments or "hafta" racket. Interestingly enough, there is a school of thought, which believes that such arrangements facilitates smooth conduct of business, and that the payments ought to be regarded as the price of services received, rather than as corrupt practices.

I was the Sub-Collector of Ongole revenue division in Prakasam district of the erstwhile Andhra Pradesh state in 1971. The entire state was experiencinga prolonged dry spell causing acute distress to the agriculture sector, especially the agricultural labour, and the small, and themarginal, farmers. As a measure of succour to the affected people, the government announced grant of 'distress taccavi' loans (as they were then known in those parts), which were essentially consumption loans meant to mitigate the loss of livelihoods on account of adverse seasonal conditions.

In order to eliminate possible malpractices by the officials at the village, firka (group of villages) and taluka levels, the government instructed the revenue divisional officers personally to undertake the task of disbursement of the loans in person. I accordingly carried cash and distributed Rs 50 each to 300 beneficiaries in one village.

Upon my return to headquarters, late that evening, I received a message that, after my departure from the village, the beneficiaries had queued up in front of the residences of the village officers and voluntarily paid them Rs 5 per head. I was naturally furious. Upon mature reflection, however, I realized that the residents of the village needed to maintain harmonious relationships with the village officers, who were a permanent part of the socio-economic structure of the village. I, as the divisional officer, was perceived as a one-off and short lived external intervention. Also, there was neither a demand for the sum the beneficiaries parted with, nor was any favour promised, or done, in return. I could have booked criminal cases under the Prevention of Corruption Act against those who paid the money as well as the village officers. I desisted, however, as such a step would, in the circumstances, be seen as an overreaction, serving no significant purpose.

The crux of the matter lies in the ability to adopt an ABC approach, of the kind which I have had occasion to deal with, in my book filled "Ethics in Governance – Resolution of Dilemmas with Case Studies." It is informed by a clear understanding of which activities require to be actively promoted, which to be mercilessly eliminated and, most importantly, the ability to live with the rest, ignoring them with determination. Quite often, the 'carrot and stick' system, akin to the reward and punishment regime referred to earlier, also proves extremely effective. A resolve, on the part of the upper echelons of the management, be it in the public or private sectors, consciously to encourage whistleblowers to expose the misdeeds of those in high places is also an important ingredient of a successful approach. From Ralph Nader, In the United States some decades ago, to Anna Hazare, and Arvind Kejriwal, there is no dearth of examples to look for.

By way of offering to the reader illustrations of the ABC approach, I shall refer to an incident from my experience in the service. The Urban Land Ceiling act was enacted in 1975, with, a view to releasing lands, in excess of a prescribed ceiling,for the central and the stategovernments to utilize for public purposes. When I took over as the Special Officer and Competent Authority under that law, I enlisted the guidance and support of Dr Y Venugopala Reddy, then the Collector of Hyderabad district, within the jurisdiction of which most of the affected lands fell. He introduced me to the facilities available at the Administrative Staff College of India, where, under his expert leadership, I was able to carry out a computerised programme of categorisation and analysis of the information contained in the declarations. Very interestingly, the results thrown up by the exercise showed that a majority of the declarations pertained to declarants who possessed insignificant excess lands, while the bulk of excess land was owned by a small number of persons. Then, in accordance with the ABC system, I proceeded to concentrate on the 'A' category – those possessing the bulk of excess land. Side by side, I was able to persuade the state government to allow those with insignificant excess land – to be exempted from the operation of the provisions of the act. The declarations falling into the middle category, namely 'B' I left to the office to handle as, after all, they also needed to have something to do!

All measures taken to combat challenge of corruption notwithstanding, little impact will be evident, unless the general public, and the victims of corrupt practices, are duly made aware of their entitlements and empowered with the ability to demand answers. Awareness generation, in the ultimate analysis, is the most powerful weapon against graft.

Before we bid adieu to this subject, I wonder if you have heard of the tehsildar in a state who was facing the threat of suspension from his superior officer. When the superior officer was asked, by a friend, why such a harsh measure was being contemplated against an essentially honest man, he retorted, "all his salary is illegal gratification!"

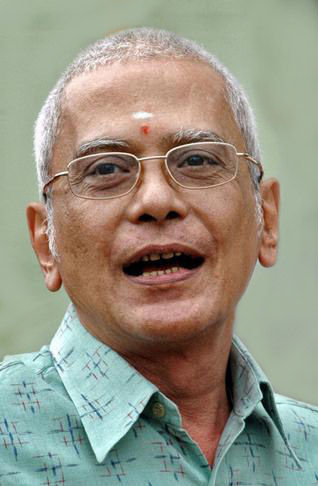

(The writer is former

Chief Secretary, Government

of Andhra Pradesh)

(The opinions expressed in this column are that of the writer.

The facts and opinions expressed here do not reflect the views

of The Hans India)