Live

- PM Modi highlights govt's efforts to make Odisha prosperous and one of the fastest-growing states

- Hezbollah fires 200 rockets at northern, central Israel, injuring eight

- Allu Arjun's Family Appearance on Unstoppable with NBK Breaks Viewership Records

- Unity of hearts & minds essential for peace & progress, says J&K Lt Governor

- IPL 2025 Auction: I deserve Rs 18 cr price, says Chahal on being acquired by Punjab Kings

- EAM Jaishankar inaugurates new premises of Indian embassy in Rome

- Sailing vessel INSV Tarini embarks on second leg of expedition to New Zealand

- Over 15,000 people affected by rain-related disasters in Sri Lanka

- IPL 2025 Auction: RCB acquire Hazlewood for Rs 12.50 cr; Gujarat Titans bag Prasidh Krishna at Rs 9.5 crore

- Maharashtra result reflects the outcome of Congress' destructive politics: BJP's Shazia Ilmi

Just In

India’s millets boom not raising farmers’ incomes

Promoting millet consumption for nutritional security is the key

In Peeliya village, around 2 km off the main road in Bassi tehsil of Jaipur district, lies a 27-bigha (about 17-acre) farmland – roughly the size of Bengaluru’s Chinnaswamy cricket stadium. The owner Kajodmal Sharma guides me through a mud-soaked trail, now slick and treacherous after a day of heavy rain, moving with the familiarity that comes with knowing every inch of the land.

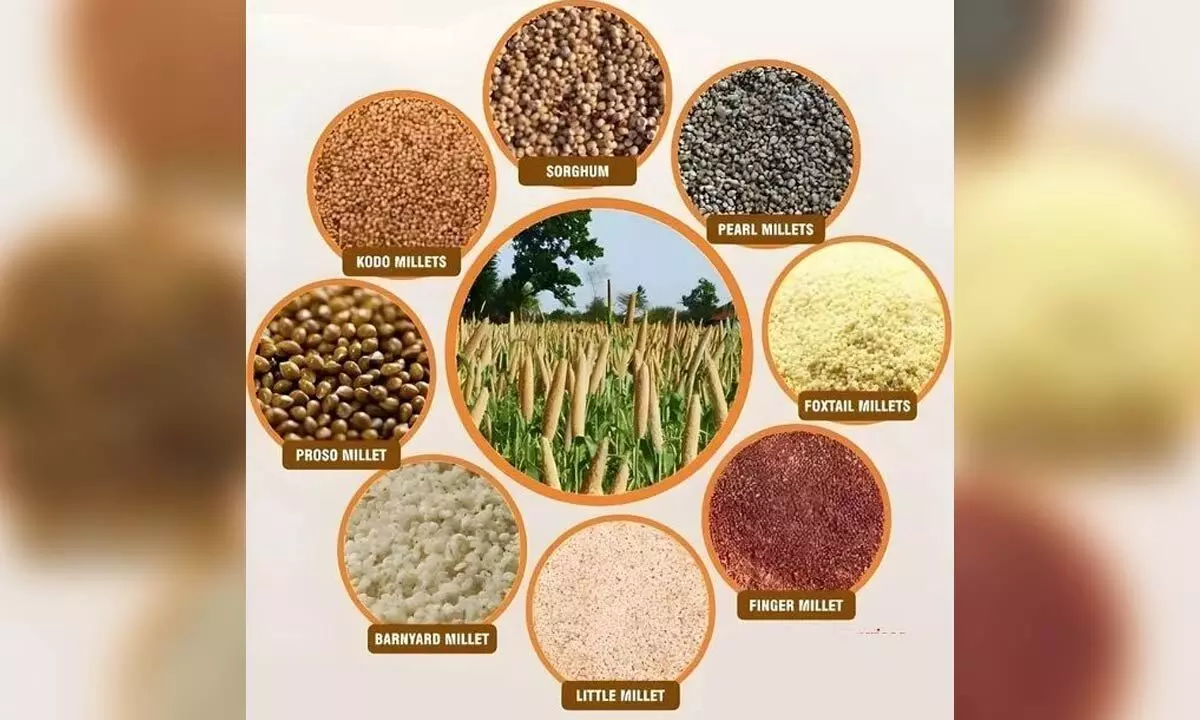

“I grow bajra (pearl millet) on this [six-acre] part of my land,” says Sharma, one of many farmers who grow the crop in Rajasthan, the highest millet producing state in India with a share of more than 30% of the country’s production of millets--a category that includes bajra, jowar, ragi, kodo and other crops.

Sharma grows some 35 quintal bajra in the summer (a quintal is 100 kg), and sells it at Rs 1,700 per quintal to a private middle-man, who then sells it to a trader, who in turn processes it and sells it onwards to prepare it for the urban market.

“For a long time, I have got returns of Rs 1,700 per quintal for bajra, and this has not changed even last year,” says Sharma, who has still not been able to sell his produce at the government’s Minimum Support Price (MSP).“They have declared MSP, but it’s not working here,” he says.

In June 2024, the Union cabinet chaired by Prime Minister Narendra Modi approved the MSP for all mandated kharif crops for the marketing season 2024-25. For bajra, the MSP was pegged at Rs 2,625 per quintal, 54% more than Sharma’s earnings and an increase of Rs 125 since the previous year.

Lallu Lal, another farmer in Peeliya village, explains that they grow fewer millets and focus more on vegetables and other crops because these sell quickly and provide a better income. He points out that if they only cultivated millets, it would be difficult to make a living since there is little demand for it. When they take bajra to the mandi, the price remains consistently low, making it unprofitable.

Why are millets expensive in urban India?

When this resilient crop which requires minimal water and is easy to grow reaches the market as a packaged product, it becomes expensive.For example, a 70-gram packet of maida noodles costs Rs 14, a 75-gram packet of wheat noodles is priced at Rs 26, while a 57-gram packet of millet noodles costs Rs 35.So, what drives up the cost of this once-humble grain when it reaches urban shelves?

“Millets are costly due to processing, transport, and value addition before reaching the market,” says Girish Khandelwal, a Jaipur-based trader who sits at the mandi in Bassi tehsil. He purchases jowar and bajra from the farmers in Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and Haryana.

“The whole thing is actually much more complex than what it appears to be,” says Shalander Kumar, scientist and deputy director of the global research programme on enabling systems transformation at the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT).

“In urban India, there isn’t a significant number of people consistently eating millet,” Kumar points out. “People might eat it today but then skip it for 15 days, or eat some millet products occasionally. The demand is inconsistent. And since demand is inconsistent, there’s more risk for value chain actors. To offset that risk, they keep the margins high.”

Kumar, who is also the cluster leader for markets, institutions and policies at ICRISAT, explains that broken value chains and inconsistent demand make it difficult for consumers to find millet products and discourage investment. As a result, small businesses and start-ups struggle to succeed in the millet sector.

Kumar, who lives in Hyderabad, highlights that wheat flour coming from north India to Hyderabad costs around Rs 22-23 per kg at the farm level, but is sold for around Rs 55 per kg in the city. In contrast, locally produced sorghum fetches farmers around Rs 18-23 per kg; yet it is sold for Rs 100 per kg. Despite being grown nearby, the price difference is significant. He further points out that although there is increasing discussion about millets in urban India, they have not yet become a regular part of people’s diets.

Rajeev Pandey, co-founder of Noida-based start-up Millets for Health, says, “Many people don’t realise that a significant portion of millet is lost during processing, which increases costs.” The loss during dehulling is four times higher for millets than for rice.

Dayakar Rao B., principal scientist at the Indian Institute of Millets Research (IIMR), emphasises that there needs to be a rise in rural consumption. “High consumer prices for millets result from technological gaps and inefficient processing,” he says, adding. “Improving machinery and techniques is crucial for reducing costs and increasing farmer profitability.”

Every step of the value chain adds expenses, Kumar observes that many industry players intentionally focus on capturing the high consumer surplus by catering exclusively to health-conscious, wealthy consumers. They aim to keep margins high by targeting a small segment--about 2-3%--who are willing to pay more for health benefits. This strategy allows them to sustain profits with lower volumes.

“Money is not really reaching the farmers in most cases,” says Kumar.

In 2021, the ICAR-IIMR in Hyderabad released a ‘Compendium of Millet Startups’ Success Stories’ featuring several millet-based startups across the country. IndiaSpend attempted to contact two Jaipur-based startups from that list--DOS and Company and Boutique Foods. However, both businesses have ceased operations entirely, the founders of these companies told us.

Way forward

Odisha Millets Mission is one of the first initiatives to focus on the comprehensive revival of millets across the value chain. It was the first initiative of the state’s Department of Agriculture & Farmers Empowerment to explicitly focus on the increase in consumption of millets.

“As part of the Odisha millet mission, we have focused on increasing millet consumption both at the local and urban levels,” Arabinda Kumar Padhee, principal secretary of the state’s Department of Agriculture & Farmers Empowerment, told IndiaSpend in a written response.

“Finger millet (ragi) occupies around 74% of the gross millet area,” Padhee noted. “Most of the finger millet produced in Odisha is either consumed locally or marketed through ragi procurement at the Minimum Support Price.

“Procurement of finger millet has risen from 0.17 lakh quintals [17,000] in 2018-19 to 4.5 lakh [450,000] quintals in 2023-24, ensuring its utilization in PDS and supplementary nutrition programs,” he adds. He said that the government of Odisha is now promoting millet service centres for marketing millets through private players by providing end-to-end services for farmers.

“We are hoping this initiative will further bridge the gap in the millet value chain,” he adds.Promoting millet consumption for nutritional security is one of the objectives of the IIMR. “For this goal, it’s important that farmers can access these grains,” Rao says, noting that FPOs will need time to learn millet processing and machinery, but success depends on better organisation, farmers’ awareness, and a strong supply chain.

(Courtesy: https://www.indiaspend.com/)

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com