Live

- BJP questions Kejriwal on 21,000 deaths in Delhi due to contaminated water

- CM Revanth Reddy Inspects Progress of Telangana Mother Statue Installation

- ‘It’s Congress habit to spread lies’, says Vinod Tawde after sending legal notice to Kharge, Rahul

- Hungarian PM invites Netanyahu for visit, calls ICC warrants 'brazen and cynical'

- Lt Gen Suchindra Kumar reviews indigenously developed ‘Asmi’ machine pistols

- Who is AP's Next CM: Chandrababu Naidu Makes Key Comments in Assembly

- Engineering goods exports shoot past $10 bn in Oct, US & EU top markets

- India’s foreign exchange reserves stand at $657.89 billion

- ‘Thandel’ kickstarts musical journey with ‘Bujji Thalli;’ win hearts

- Kerala Actress Withdraws Sexual Abuse Allegations Against Industry Figures, Cites Government Negligence

Just In

You tell her that you read somewhere that the most beautiful places in the world are cursed with conflict. She pauses, and whispers that she didn't really emotionally investigate that thought in the book.

You tell her that you read somewhere that the most beautiful places in the world are cursed with conflict. She pauses, and whispers that she didn't really emotionally investigate that thought in the book.

You then ask what is the first image that comes to her mind when she hears the word 'Kabul'? She says, almost immediately, "Mountains.

And snow sitting on top of them".

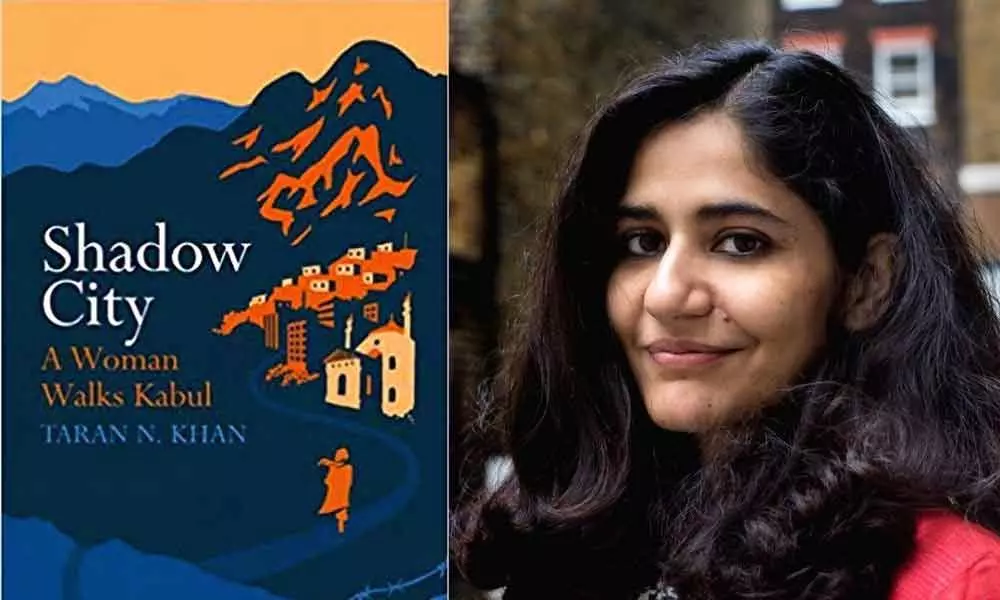

Author Taran Khan's 'Shadow City: A Woman Walks Kabul', published recently by Penguin Random House India captures the Afghan capital through the writer's eyes, who has been spending time there since 2006, and reveals a fragile city in a state of flux: Stricken by near-constant war, but flickering with the promise of peace, a shape-shifting place governed by age-old codes, but experimenting with new modes of living.

She goes to the unvisited tombs of the dead, and to the land of the living: The booksellers, archaeologists, intrepid filmmakers and entrepreneurs who are remaking and rebuilding this ancient 3,000-year-old city.

Talking about the city, Khan emphasizes that she wouldn't want to create a romantic vision of Kabul or use the cliche 'there is more to the place than war' because that would also be a kind of disservice. She thinks it is always important to describe people as people while writing about them.

"For me, the key was to shed light on everything - the nuances, the situations, the entire environment. I think that's what I really enjoy doing in this book - essentially talk about the humanity of these people by focusing on specifics, by stressing on their experiences."

Insisting that for her the overwhelming emotion in people there was humanity, great humour, warmth and extraordinary hospitality - as decades of conflict has taught them how quickly life could change, and it was therefore important to hold on to those qualities.

"I felt that warmth when I went for the first time and I continue to feel it, even today. I certainly never felt that they were uni-dimensional and defined by their suffering, unlike how they have been portrayed by the media."

Stressing that she was still in touch with many of the characters in the book, even those who have left Kabul and taken refuge in different countries, Khan adds, "Some of them were in the process of leaving when I was there.

Things have changed for them as well, but these are relationships that are continuing, beyond the life of a book."

The author reveals that she didn't set out to write the book in a certain way, but in fact derived the essence from meeting people over several years, observing things that changed and remained unchanged in their lives.

"There was both continuity and alteration. They were generous enough to include me in their lives. That helped me get the perspective - that comes from participation and observing the every day.

You know that automatically gives you a way, layers to talk about complexity or ordinariness. And the latter can be a wonderful thing.

You often don't get to hear that quality about Kabul... how ordinary days are, how everyday life goes, what do you do when you are sitting by a window and reading. I was fortunate enough to see and describe that."

Interestingly, fortified and high security-areas, and not the streets and people's homes made her uneasy and insecure.

She laughs, "Maybe that's just me. Honestly, if I was in an armoured car, moving through the city's traffic, I felt very 'exposed' For me, it was always less frightening to be a regular, normal home or a restaurant."

Though she had been writing elaborate pieces for different publications from Kabul since 2006, somewhere along the way, it stuck her that maybe she was just scratching the surface.

"It was a peculiar 'writer' instinct.

I felt there was something more, and there was a different way of getting at that. So, I started writing longer stories, which went into lucid themes, which I found very enjoyable. I kept writing them and finding places to pitch them --- and I thought yes, there is a book here, somewhere."

However it was only after she left Kabul in 2013 that she actually started writing the book.

Ask her if the 'distance' helped put things in perspective, and she asserts, "Yes, I think leaving Kabul was part of the writing process and helped me see patterns. I could see how things connected and could therefore move pieces around in a freer way."

Khan, who wrote three drafts, admits that being a journalist did help, as she didn't feel that she was attempting something dramatically different.

"I had the discipline of writing. Of course, this book required a completely different kind of immersion and I loved every moment of it, despite it being extremely difficult.

Also, a lot of help came my way - friends and other writers who would read drafts and encourage. If I weren't a journalist, I wouldn't have this community of people who understood the process and could hold me up when they felt my resolve wavering. I also had access to resources that I could ask other journalists for help. I knew where I needed to look when I need information."

She is not worried going back to journalism - with its demand of set templates and word counts... "I like writing non-fiction generally and not worried about getting bored with it. In fact, the last series I did was about Afghan refugees in Germany, an eight part series boasting of about 24000 words."

So, we can expect a non-fiction now? She laughs, "Well, why can't we expect it? I would love to work on another book, but it has to be something consuming. I would like to find something that I can invest myself in, something that can hold myself with the kind of power that Kabul did."

Ask her about her plans to go back to Kabul and if she will encounter the city through the book's prism, and Khan says, "No immediate plans but if I go back, I know it will be to a very different city.

In the book, I looked through the prism of my memories. The people I spent so much time with there, don't live in Kabul anymore. But yes, when I meet them in different parts of the world, it is like the city takes a form there, and comes alive beyond its geography..."

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com