The tragedy of children recruited and used in armed conflict must stop

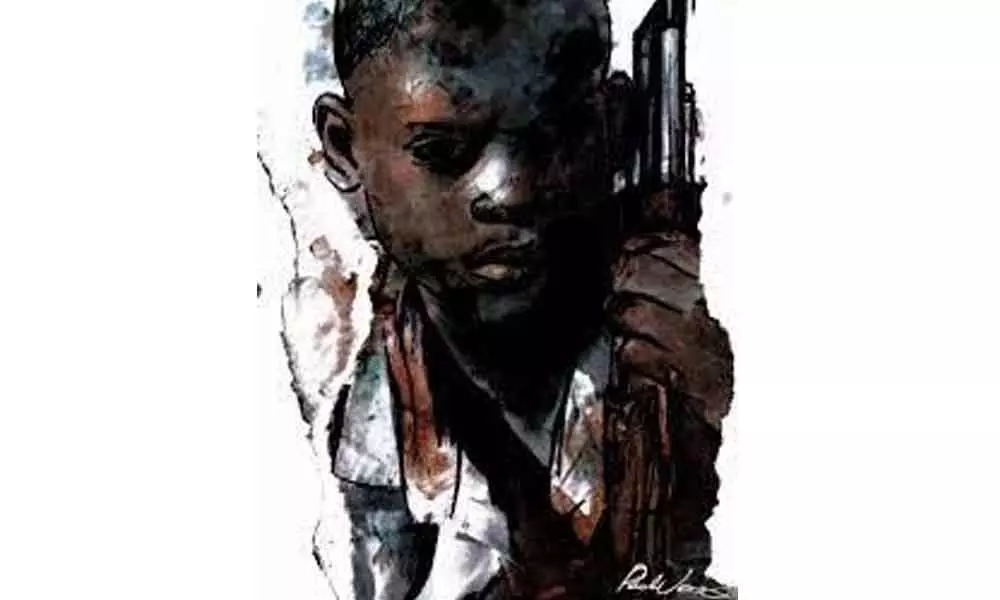

Representational Image

Frederique was in school in Bambari, Central African Republic, when the militia attacked. Many people died in the hostilities, including his brother and mother.

Frederique was in school in Bambari, Central African Republic, when the militia attacked. Many people died in the hostilities, including his brother and mother. Devastated, Frederique joined an armed group, seeking both protection and revenge for the death of his loved ones.

Frederique's story is shocking but unfortunately not rare. Armed conflict is a tragic reality for millions of children and in at least 20 countries around the world, girls and boys are recruited as soldiers, lookouts, porters, spies, cooks, or sexual slaves.

The international community has committed to ending the recruitment and use of children in armed conflict by 2025. The UN International Year for the Elimination of Child Labour (2021) provides an excellent opportunity for the international community to take concrete steps and accelerate action to put an end to this scourge.

Over the last 25 years, many countries have shown their commitments to protect children against recruitment and use by parties to conflict through the ratification and implementation of key international instruments, by releasing all children from their ranks and by putting in place mitigation measures for their security forces such as age verification mechanisms, child protection trainings and military command orders.

However, progress remains too slow. The Covid-19 pandemic has put an additional burden on the protection of conflict affected children. The closure of some of the most protective environments for children, namely schools and child friendly spaces, coupled with the loss of family income, may have incentivized parties to conflict to take advantage of children's increased vulnerabilities or pushed children to join armed groups and forces or engage in other forms of exploitative labour to raise family income. The pandemic and related confinement measures have also made it more difficult for child rights organizations to monitor child recruitment and use and to put in place education and healthcare programmes contributing to halting and preventing this practice.

The recent ILO and UNICEF Child Labour Global Estimates for 2020 show that for the first time in the last two decades, progress on ending child labour has stagnated and figures are starting to rise again. At least 160 million children are currently engaged in child labour and many more are at risk.

A renewed international commitment is needed to end and prevent the recruitment and use of children once and for all by 2025 and to avoid that more children are pushed into this worst form of child labour as a consequence of COVID-19.

For Frederique and all children who have suffered at the hands of armed forces or groups, separation is only the first step on a long and difficult road to recovery. International law recognizes released or separated children as victims of grave human rights violations who require long-term support. Yet too many do not receive adequate assistance and face the risks of being re-recruited, trapped in other forms of child labour, exposed to human trafficking, or detained for their association with an armed group.

Building forward better means that Governments must put the needs of girls and boys at the centre of COVID-19 recovery plans and put in place reintegration services to allow children associated with conflict parties to reclaim their lives. Reintegration programmes also need to recognize the high levels of distress that children have suffered and provide holistic support combining physical recovery, psychological care, family reunification, education, social protection and help for social, political, and economic integration back into civilian life.

To that end, the international community must provide long-term and predictable funding as such holistic child reintegration programmes are contributing to sustainable recovery, development, as well as reconciliation, prevention, and peace efforts. A substantive proportion of funding should also be directed to community-led initiatives and organizations working at the frontline as they are best placed to evaluate children's and communities needs and aspirations

Supporting communities to identify and work towards their own solutions is key to the success of reintegration programming and requires that we, the international community shift our way of supporting reintegration to one deeply rooted in the child and its community's needs while building on existing resources and capacities.

This important year presents a unique opportunity for the international community to translate its commitments into actions and accelerate efforts to fully end and prevent the recruitment and use of children in armed conflict. Governments, civil society, workers organization and the private sector have the capacity to end this scourge and hence further laying the foundation for peaceful societies.

(The authors are UN Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict, CEO, War Child UK and ILO Director-General respectively)