The books that can help

Brimming over with challenging calculations, daunting data, and formidable formulas, science seems an intimidating prospect for many people.

Brimming over with challenging calculations, daunting data, and formidable formulas, science seems an intimidating prospect for many people. This seems true for both young people -- despite their parents' best efforts -- and their elders who studied it: they have either forgotten most of it, or retain a garbled or even erroneous recollection.

This comes even as STEM learning/careers are being emphasised. The basic principles of science are more important now than ever -- especially in our post-truth age. Scores of other disciplines, and even certain activities, seek validity by adding science to their names, or comparing themselves with it.

Why science, across its various realms, seems such a fearsome prospect can be explained by an array of psychological, social, pedagogical, and even political factors. But while examining these, the question that arises, for the purpose of this piece, is can and how books can help in the situation.

First, let us examine some of the reasons why science seems so difficult. At the outset, it must be said that the left brain (arts and humanities) / right brain (science/mathematics) theory is plainly wrong, with lateralisation of brain functions usually being unique for every individual and native language, gender, dominant hand, and so on being the key factors in this regard.

Unless there is a learning disability, almost anybody can study science with enough practice. That some may find it boring / dreary is another thing -- but then that has more to do with the quality of teaching and teaching materials, and to be fair, applicability in daily life.

Take teaching of mathematics in schools. This usually comprises five-six years of number crunching, which a basic calculator can do faster and without mistakes, followed by delving into abstract areas such as algebra and calculus. With the focus more on techniques than on applications, its basic purpose -- of how some real-life problems can be converted into mathematics to find a solution gets ignored.

In other sciences too, if they are just taught to pass examinations, or serve merely as pathways to careers in applied subjects such as engineering or medicine, and be jettisoned at the first opportunity, they are not going to gain many interested adherents.

And then, the socio-political factors, including distrust of experts/intellectuals. Scientific aptitude, be it prowess or just interest, postulates curiosity, the propensity to ask (lots and lots) of questions -- including ones on received wisdom and current theories -- and argue much, the insistence on verification, and so on. You can gauge how many of these attributes are welcome in a milieu where faith, tradition, "alternative facts", emotions, and sweeping statements meant to be taken as gospel truth are getting priority.

But, as mentioned, a lot of lack of interest in science can be attributed to a lack of insightful and relevant content to engage interest across various age groups, or what we call popular science, or science for the layperson. But this is not a recent innovation, and has existed since the early 19th century.

Scottish scientist and polymath Mary Somerville's "On the Connexion of the Physical Sciences" (1834), describing the status, in her time, of astronomy, physics, chemistry, geography, and others -- with minimal diagrams or mathematics -- was a bestseller that went through at least 10 editions and was translated into various languages.

Then, there are works by the likes of naturalist and climate change crusader Sir David Attenborough, environmentalist Rachel Carson, physicists Paul Davies, Stephen Hawking (and daughter Lucy Hawking), evolutionary biologists Richard Dawkins and Jared Diamond, brain physiologist Susan Greenfield, neurologist Oliver Sacks, and astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson, and others explaining their specialised fields for the general reader.

Closer to home, we have had Atul Gawande, Siddhartha Mukherjee, Jayant Narlikar, and V.S. Ramachandran, among others. It's unfortunate that Prof. Yash Pal never wrote a book or someone collated his pieces for publication.

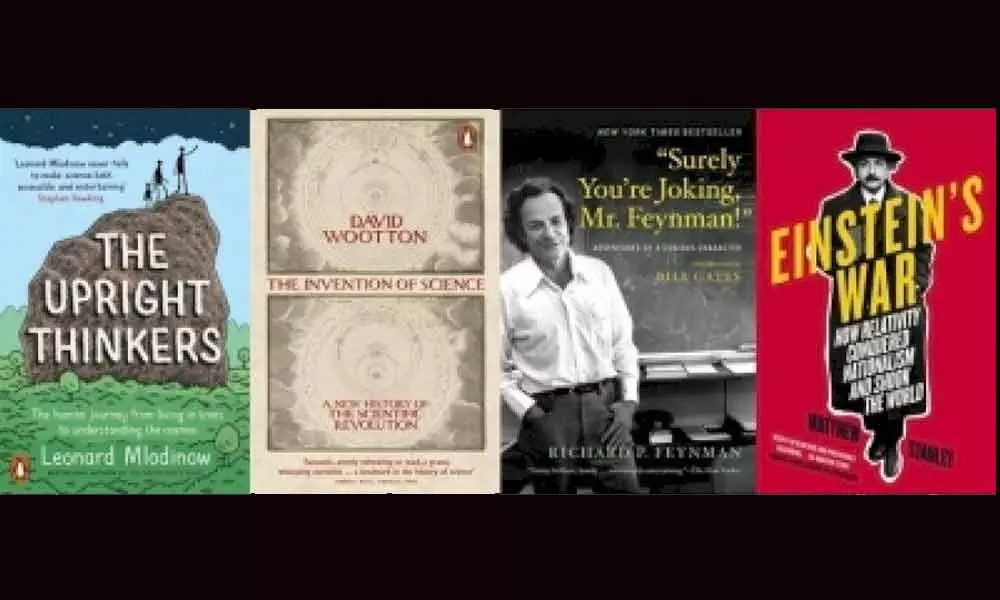

Those who grew up in the 1980s might also recall a range of some invaluable popular science books -- at unbelievably low prices -- by Soviet publishers such as Progress and Mir. Dmitri Nicolaevich Trifonov's works like "Silhouettes of Chemistry", "Chemical Elements: How They Were Discovered" and "The Price of Truth: The Story of Rare-Earth Elements", among many others, were a sparkling introduction to chemistry. It is our intention to deal with the fundamental sciences -- physics, biology, chemistry, mathematics and their key sub-disciplines -- separately over coming installments, let's begin with a few books that give an overarching idea of science over the last few centuries. Though these may deal mostly with what is called "western science" and may not focus much on the rest of the world, even that has a reason as we shall learn.