Researchers Discovered The Eggs Of Intestinal Parasites In Five Petrified Faeces

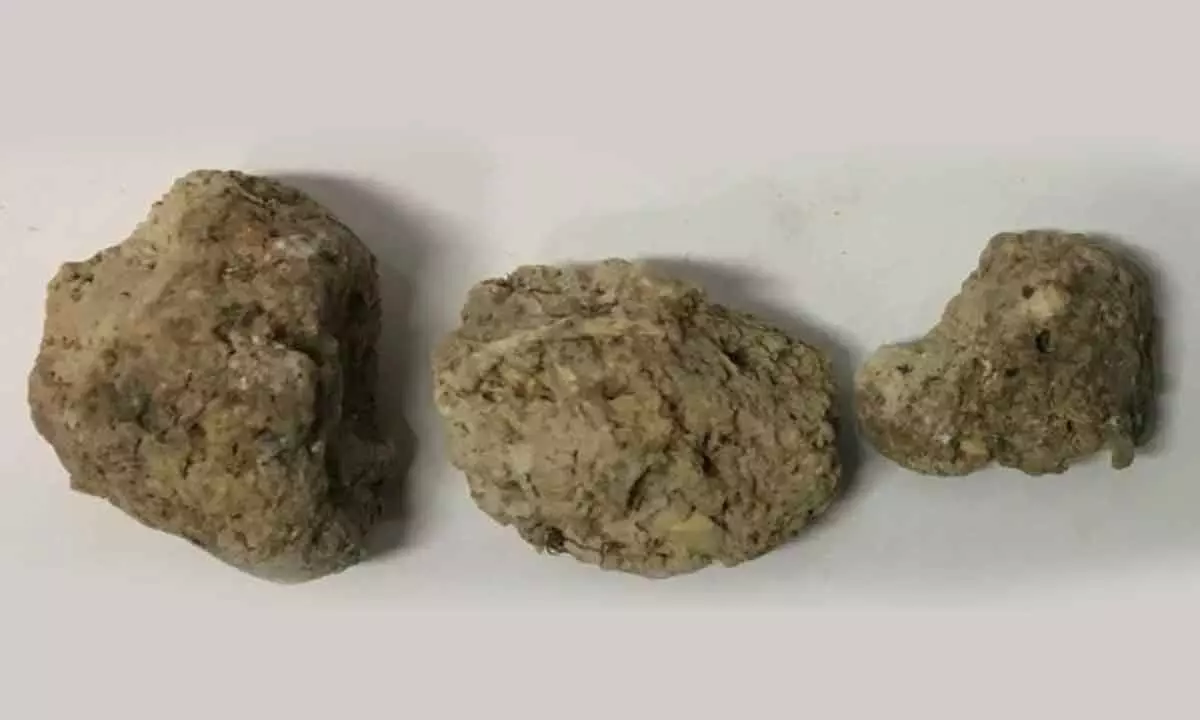

Preserved human feces from Durrington Walls. (Lisa-Marie Shillito)

- Archaeologists have been excavating through historical dung from Jerusalem to Rome to Greece to learn more about the diets and diseases of long-gone civilizations.

- Researchers discovered intestinal parasite eggs hidden within five petrified faeces in the neighbouring hamlet of Durrington Walls

Humans have a long and complicated history with intestinal parasites, which is documented in faeces or dung. Archaeologistshave been excavating through historical dung from Jerusalem to Rome to Greece to learn more about the diets and diseases of long-gone civilizations.

Intestinal parasite epidemics were widespread among both the rich and poor in Europe for thousands of years, according to the data so far.These small worms were most likely carried by the individuals who built Stonehenge.

Researchers discovered intestinal parasite eggs hidden within five petrified faeces in the neighbouring hamlet of Durrington Walls, the Neolithic site where archaeologists believe the creators of Stonehenge once lived.

The coprolites, or preserved poops, are more than 4,500 years old; one was human, and four were dog. Capillariid worms' lemon-shaped eggs were found in four of the five coprolites.

These tapeworms are recognized to infect cattle and other grazers, and the discovery of eggs in human poop provides archaeologists with clues as to what Neolithic people may have eaten while constructing Stonehenge. Researchers believe the Durrington community ate raw or undercooked cow intestines, lungs, or livers while constructing the ancient timekeeping system that still remains today.If a cow was infected with a tapeworm before being slaughtered for the winter, the parasite might readily enter the human intestine and pass straight through.

Earlier archaeological study at Durrington supports the findings, indicating that livestock were routinely butchered in the winter. According to chemical research, some of the livestock slaughtered in the winter came to Durrington from other parts of southern England, possibly even northern England.

Meanwhile, t he findings are 'intriguing,' as per the scientists because there is very little evidence of fishing in the Late Neolithic period in Britain. However, it appears like a dog has caught a fish in some way.

Next Story