Live

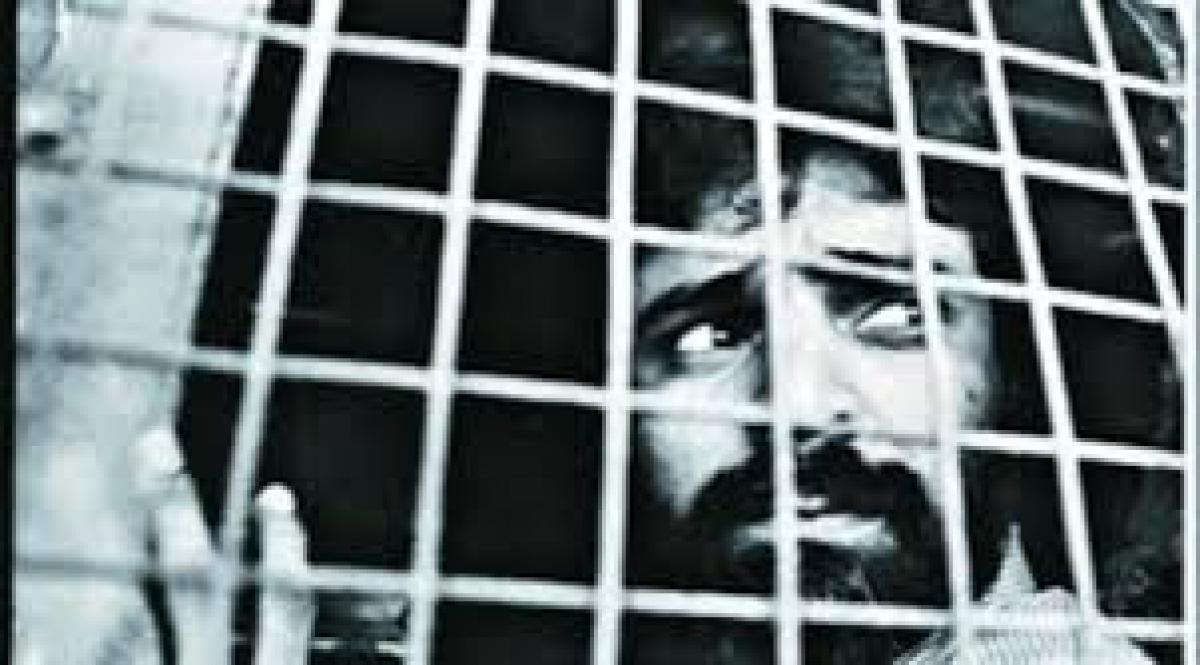

- Pakistan Protests: PTI Supporters March Towards Islamabad, Demanding Imran Khan's Release

- Additional Collector Conducts Surprise Visit to Boys' Hostel in Wanaparthy

- Punjab hikes maximum state-agreed price for sugarcane, highest in country

- Centre okays PAN 2.0 project worth Rs 1,435 crore to transform taxpayer registration

- Punjab minister opens development projects of Rs 120 crore in Ludhiana

- Cabinet approves Atal Innovation Mission 2.0 with Rs 2,750 crore outlay

- Centre okays Rs 3,689cr investment for 2 hydro electric projects in Arunachal

- IPL 2025 Auction: 13-year-old Vaibhav Suryavanshi becomes youngest player to be signed in tournament's history

- About 62 lakh foreign tourists arrived in India in 8 months this year: Govt

- IPL 2025 Auction: Gujarat bag Sherfane Rutherford for Rs 2.60 cr; Kolkata grab Manish Pandey for Rs 75 lakh