Live

- Istanbul nabs over 240 illegal migrants

- BJP slams Mehbooba Mufti for remark on Indus Water Treaty

- Global brokerage CLSA shifts ‘tactical allocation’ to India from China

- Istanbul nabs over 240 illegal migrants

- Haryana CM takes dig at Punjab counterpart on setting up of new legislative Assembly

- Avvatar India and Spartan Race Kick Off India’s Ultimate Fitness Challenge in Bengaluru

- CM Revanth Reddy Pays Tribute to Guru Nanak on His Birth Anniversary

- ‘Matka’ clears censor: run-time locked

- ‘Kubera’ first glimpse looks interesting

- It took me 20 years to reach Sahnkar sir’s ears: Thaman S

Just In

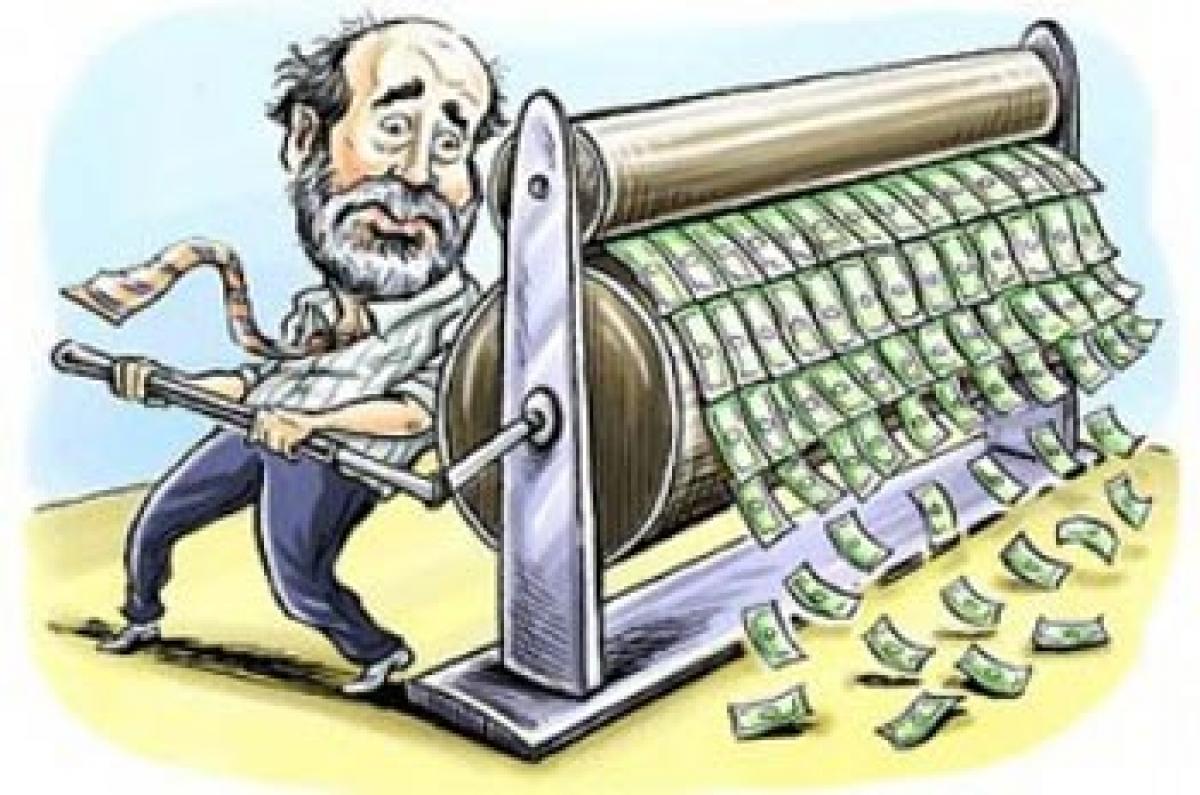

Ahead of the US Federal Reserve taking a call on interest rates, there was a clamour for further reversing the effects of quantitative easing (QE).

.jpg) Ahead of the US Federal Reserve taking a call on interest rates, there was a clamour for further reversing the effects of quantitative easing (QE). It was expected to raise interest rates for the first time since June 2006 from near-zero levels. It is said that though banks’ reserves swelled in the US due to QE, it did not see increase in lending as Fed was paying interest on banks’ reserves.

Ahead of the US Federal Reserve taking a call on interest rates, there was a clamour for further reversing the effects of quantitative easing (QE). It was expected to raise interest rates for the first time since June 2006 from near-zero levels. It is said that though banks’ reserves swelled in the US due to QE, it did not see increase in lending as Fed was paying interest on banks’ reserves.

In its latest move, the US Federal Reserve has raised interest rates by 0.25 percentage points - its first increase since 2006. Earlier, the European Central Bank announced tamer-than-expected quantitative easing measures; it also offered a bit of reassurance to those counting on a broader QE program. Bank President Mario Draghi said that the ECB was prepared, if necessary, to implement further easing, writes seekingalpha.com.

The Economist explains that central banks are responsible for keeping inflation in check. Before the financial crisis of 2008-09 they managed that by adjusting the interest rate at which banks borrow overnight. If firms were growing nervous about the future and scaling back on investment, the central bank would reduce the overnight rate. That would reduce banks' funding costs and encourage them to make more loans, keeping the economy from falling into recession.

By contrast, if credit and spending were getting out of hand and inflation was rising then the central bank would raise the interest rate. When the crisis struck, big central banks like the Fed and the Bank of England slashed their overnight interest-rates to boost the economy. But even cutting the rate as far as it could go, to almost zero, failed to spark recovery. Central banks therefore began experimenting with other tools – one of them was QE.

To carry out QE central banks create money by buying securities, such as government bonds, from banks, with electronic cash that did not exist before. The new money swells the size of bank reserves in the economy by the quantity of assets purchased—hence "quantitative" easing.

Like lowering interest rates, QE is supposed to stimulate the economy by encouraging banks to make more loans. The idea is that banks take the new money and buy assets to replace the ones they have sold to the central bank. That raises stock prices and lowers interest rates, which in turn boosts investment, adds the Economist.

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com