Live

- India Urges $1.3 Trillion Annual Climate Support for Developing Nations

- Bad air: 106 shuttle buses, 60 extra Metro trips planned to make Delhiites give up cars

- WHO reports declining monkeypox cases in Congo

- CM Attends Kotideepotsavam on Kartika Purnima

- PKL Season 11: Raiding trio of Devank, Ayan, Sandeep help Patna Pirates rout Bengal Warriorz

- Food waste crisis fuels sustainable practices across APAC food & beverage industry: Report

- AI helps erase racist deed restrictions in California

- ATMIS completes third phase of troops' drawdown in Somalia

- PM Kisan Samman Nidhi scheme bringing smile to Nalanda farmers

- German economy forecast to lag eurozone growth until 2026

Just In

Undoubtedly, you would have been to Bombay at various times. Jinnah sahib would have seen much of the city. But why would you have seen our bazaar? I live in a bazaar known as Faras Road; it is situated between Grant Road and Madanpura. On the other side of Grant Road is Lamington Road, Para House, Chowpati, Marine Drive and Fort.

Undoubtedly, you would have been to Bombay at various times. Jinnah sahib would have seen much of the city. But why would you have seen our bazaar? I live in a bazaar known as Faras Road; it is situated between Grant Road and Madanpura. On the other side of Grant Road is Lamington Road, Para House, Chowpati, Marine Drive and Fort.

These areas are contained within the vicinity of the civilized classes of Bombay. Across Madanpura is where the poor classes live. Faras Road sits in between them—so that the rich as well as the poor are equally benefited. But Faras Road is much closer to Madanpura, because the distance between a destitute and a prostitute is always small.

This bazaar is not beautiful, neither are its occupants. The middle of the bazaar is filled with the continuous noise of the tram and large numbers of stray dogs, loafers, dandies, wastrels and professional criminals can be found roaming about its streets. The lame or the handicapped, the wastrels, the hooligans, cocaine addicts and pickpockets, those with chronic diseases, the gonorrhoea-ridden bald men—all enjoy a free run of the market.

There are many notions and perceptions attached to women in prostitution. Some consider that women find freedom from patriarchal structures in prostitution; that college girls prostitute themselves for the sake of consumerism – to buy shoes, lipsticks, bags, perfumes…

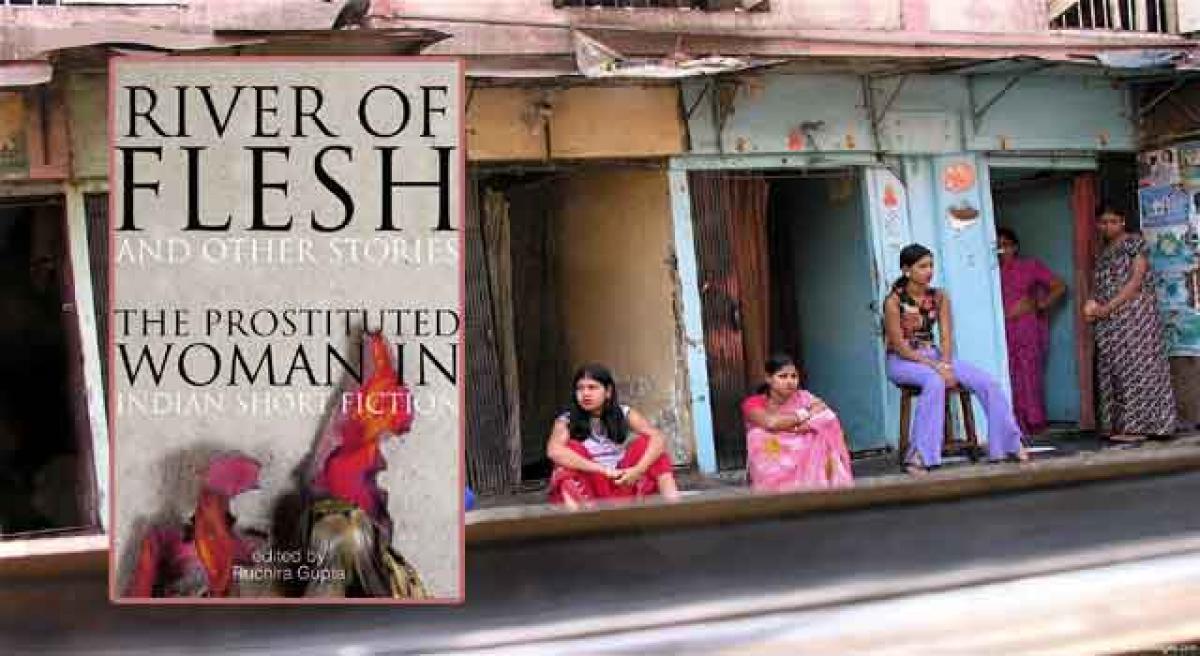

There are some who are convinced that prostitution is a livelihood choice many women make when confronted with sweat shop work, domestic servitude and oppressive marriages. The reality, as witnessed by Ruchira Gupta, who edited the book, ‘River of Flesh’, a long-time activist organising girls and women suffering from inter-generational prostitution in the red light districts, was very different. She saw very little ‘agency’ in their lives, which is marred with violence, desperation and destitution

There are filthy hotels, countless flies buzzing on the litter spread over damp footpaths, large warehouses of wood and coal, professional pimps and vendors of stale garlands, owners of old and decaying film magazines, sellers of sex manuals such as Kokashastra and of naked and obscene photographs, Chinese and Muslim barbers and abusive, langot-clad wrestlers. All the garbage of our society can be found on Faras Road. …

Perhaps you might be thinking that Bela and Batul are my daughters. No. This is not true; I have no children. I bought both girls from the bazaar. During the days when Hindu–Muslim riots were at their peak, and human blood was flowing like water on the streets of Grant Road, Faras Road and Madanpura, I purchased Bela for three hundred rupees from a Muslim pimp.

He had brought Bela from Delhi. Bela’s parents lived in the street in front of Poonch House, Rawalpindi. Her family was middle class; decency and simplicity flowed in their blood. Bela was their only daughter. She was only in the fourth standard when Muslims massacred Hindus in Rawalpindi on 12 July. …

Illiterate Batul came to live with me recently. A Hindu pimp brought her to me, and I bought her for five hundred rupees. I have no idea where she was before she came here. Yes, the ladydoctor has said so many things about her—you might go mad if I tell you everything. Batul is not in a sound state of mind.

Her father was murdered brutally by the Jats. The killing has shattered the six-thousand-year-old history of Hindu civilization, and human barbarity has appeared in a cruel state before everyone. First, the Jaats plucked out his eyes and then urinated in his mouth. They slit his throat and then cut his body and took out his intestines.

They also raped his married daughters. Rehana, Gulwarkhas, Marjana and Sosan Begum were raped, one by one, in front of their father’s corpse. Sisters and mothers were raped by men to whom they had once sung lullabies or had lowered their heads in front of, out of modesty, piousness and shyness.

The Hindu religion has lost its reverence and has destroyed its ethos and customs. Today, silence prevails; each and every verse of the Granth Sahib is ashamed and every verse of the Gita is injured. Who can talk about the artistry of Ajanta in front of me now? Who can tell me about the writings of Ashoka? Who can sing in praise of the sculptor of Ellora?

On the helpless chewed-up lips of Batul, in the teeth-marks of brutes and demons on her arms, in her disfigured limbs, lies the death of your Ajanta, the funeral of your Ellora, and the shroud of your civilized society. Come, come, I will show you the beauty that once Batul was. I will show you the unburied living corpse that Batul now is.

I have said so many things because of my overwhelming sentiments. I shouldn’t have done so. You might feel offended by it. Perhaps, until now, nobody would have told you such things. You may not be able to do anything for us at all. But since both India and Pakistan have gained independence, perhaps even a prostitute now has the right to ask a question to her leaders: What will happen to Bela and Batul?

Bela and Batul are not only two girls, but two communities and two civilizations. They are temple and mosque. Batul now lives in the house of a prostitute who conducts her business near the Chinese barbershop. Neither Bela nor Batul enjoy this. I have bought them. If I wished, I could force them into this business, but I will not do what Rawalpindi and Jalandhar did to them.

Until now, I have kept them distanced from the world of Faras Road, but when my clients go to my back room to wash their hands and legs, Bela and Batul’s eyes communicate something to me. I cannot tolerate that gaze. I cannot even communicate their message to you properly. Why don’t you comprehend the message in their eyes for yourself?

Panditji, I wish for you to adopt Batul as your daughter and Jinnah sahib, I want you to adopt Bela as your daughter. Please take them away from the clutches of Faras Road. Take them to your homes; listen to the pleas of lakhs of souls. The same plea echoes from Noakhali to Rawalpindi and from Bharatpur to Bombay.

Is this plea inaudible in government houses? Will you not listen to our voice?

Yours sincerely,

A Prostitute of Faras Road

(Excerpts from River of Flesh and Other Stories: The Prostituted Woman In Indian Short Fiction, edited by Ruchira Gupta, published by Speaking Tiger, `350.)

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com