Tracing the history of Purdah in India

In medieval Indian society, purdah was common with the Muslim ladies. Strict purdah originated with Amir Timur, when he conquered India and entered in this country with his army and womenfolk. He made the proclamation, ‘As they were now in the land of idolatry and amongst a strange people, the women of their families should be strictly concealed from the view of stranger’.

In medieval Indian society, purdah was common with the Muslim ladies. Strict purdah originated with Amir Timur, when he conquered India and entered in this country with his army and womenfolk. He made the proclamation, ‘As they were now in the land of idolatry and amongst a strange people, the women of their families should be strictly concealed from the view of stranger’.

Purdah, thus, became common among the Muslim ladies, although it was not as rigid with the Hindu women. A girl started observing seclusion near her puberty and generally, continued to adhere to it till her death. Although the tenets of the Quran allowed her to dispense with it after she passed the childbearing age, but by that time, she got so much used to it that she felt more comfortable living in seclusion than out of it.

The Muslim men were very zealous in guarding their women from public gaze and considered it a dishonour if they were exposed unveiled. Monserrate, mentioning about harem ladies of Akbar’s time, wrote that they ‘are kept rigorously secluded from the sight of men’.

Similarly, Manucci, writing during the time of Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb, recorded, ‘[T]he Mahomedans are very touchy in the matter of allowing their women to be seen, or even touched by hand….’ At other place, he writes that amongst them, ‘it was a great dishonour for a family when a wife is compelled to uncover herself’.

He also refers to an incident concerning this wherein a soldier was travelling in a cart along with his wife and daughter, when the tax collectors tried to check his cart by force. The soldier became so furious that he chopped off the head of that tax collector and also wounded many of his attendants.

Thereafter, feeling dishonoured, as his wife and daughter had been seen by the tax collectors, he killed both the ladies too. Similarly, Amir Khan, a noble, felt dishonoured when his wife could not observe purdah in an effort to save her life by jumping from the back of an elephant she was riding, who had run amuck, and decided to divorce her. It was at the intervention of Shah Jahan, who rebuked him and forbade him from doing so.

They were so much protective of their women that they would not allow their wives to talk even to their relatives except in their presence. Consequently, all Muslim ladies, except those belonging to peasant or inferior servants, followed purdah strictly.

Two factors were mainly responsible for this. Firstly, since the royalty and nobility religiously practised it to maintain their exclusiveness, it came to be regarded as a symbol of respectability. It percolated down but only to the extent the lower classes were able to afford it.

Secondly, the threat of invaders and also the sensual laxity and outrages perpetrated by the Muslim royalty and nobility of the sultanate and the Mughal periods had instilled a sense of insecurity among the Muslim subjects and also among the Hindus.

Consequently, they relegated their women meekly behind the purdah so as to save them from the lustful eyes of these masters. The more was the slackening of the morals, the stricter became the rules of women seclusion. A majority of the Muslim population of India were Hindu converts.

These neo-Muslims were more zealous in following the tenets of the ‘Faith’ embraced than those to whom it came as a matter of course. Such persons enforced the purdah norms most assiduously upon their womenfolk. …

From the beginning, the royal and aristocratic classes, with the exception of the Turkish women and a few others, were more rigid in adhering to the rules of purdah. Not only the walls of the harem became higher and stronger with the passage of time, the restrictions imposed also increased successively.

So strict was their seclusion that even when they fell ill, the attending doctors were not allowed to touch and feel their pulse. Therefore, for their examination, a handkerchief was first wrapped all over the body of the patient, this cloth was then dipped into a jar of water and it was through its smell that they were required to diagnose the disease and prescribe the medicine.

152 Later on, some selected physicians like Bernier and Manucci were allowed to feel the pulse of the harem ladies. But such special privilege was given to them only after an established familiarity and a long testing. They were also subjected to surprise checks.

Manucci narrated that once when he stretched his hand inside the curtain to feel the pulse of a lady-patient, it turned out to be the hand of Shah Alam himself. Nonetheless, these physicians were not permitted to see the ladies.

Whenever their services were required inside the harem, their heads were covered by the thick shawl hanging down to their waist or feet and were led in and brought out like blind men by the eunuchs. The ladies also were such touch-me-nots that if they were to show some ailing part of their body to the doctor, they would see to it that he could see only that part.

Even the old mother of Shah Alam, who needed to be operated upon for gout twice a year, would put her arm out from the curtain, only uncovering two fingers wide of the affected part and the rest of it would be carefully covered with cloth.

The whole outer world was inaccessible for these ladies. If ever they moved out, it was in covered palkis and dolas surrounded on all sides by alert guards. So much so that if they were to travel on elephants, they would ride them inside a tent pitched near the palace gate.

Even the mahouts of the elephants covered their heads so that they could not see the royal ladies while they rode the animals. On the elephant -backs, they sat inside covered haudas. Their slave girls were also made to move in covered conveyances. The slave girls of Tatar Khan, a noble of Sultan Firoz Shah Tughlaq, were reportedly carried in locked conveyances lest the eyes of na-mahrams would fall on them.

Purdah, in-fact, had come to be regarded as a symbol of honour. The worst punishment they could think of for their enemies was to parade their womenfolk unveiled and best honour they could extend to a person was by asking their harem ladies to unveil themselves before him. …

Numerous references of observance of purdah are found in the writings of the contemporary foreign travellers. Barbosa wrote that the Mohammadans of his time (he visited Bengal and Cambay) kept their women carefully guarded.

Thereafter, a number of them—Monserrate of the time of Akbar, Terry and Della Valle of the time of Jahangir, De Laet of the time of Shah Jahan, Manucci of the time of Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb, Ovington, Thevenot, Careri, Fryer and Marshall of the time of Aurangzeb and Hamilton of the period of Aurangzeb and beyond (1666–1732 A.D.) – confirmed this view.

Many of them described categorically that purdah had come to stay as a symbol of decency, status and modesty and only women of easy virtues or of the poor families were seen out moving without veils.

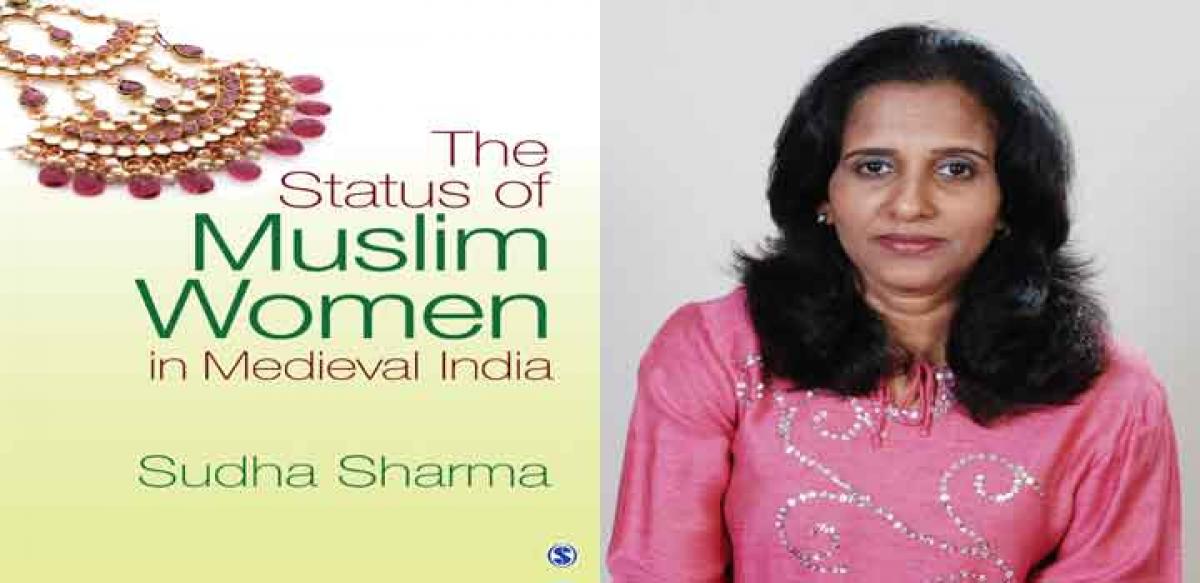

(Except from ‘ The Status of Muslim Women in Medieval India’ by Sudha Sharma; SAGE Publications; `750)