Live

- Beautification works to pick up pace in city

- Dozen flyovers to come up in Visakhapatnam

- NDA govt is controlling prices effectively: Dinakar

- Jagan govt didn’t pay even kids’ chikki bills: FM

- Bomb Threat at Shamshabad Airport: Passenger Detained, No Explosive Devices Found

- CID probe soon into past irregularities in excise dept

- FiberNet to provide 50 lakh cable connections

- Gold rates in Hyderabad today surges, check the rates on 16 November, 2024

- Gold rates in Visakhapatnam today surges, check the rates on 16 November, 2024

- Fire breaks out at an apartment in Manikonda, no casualties

Just In

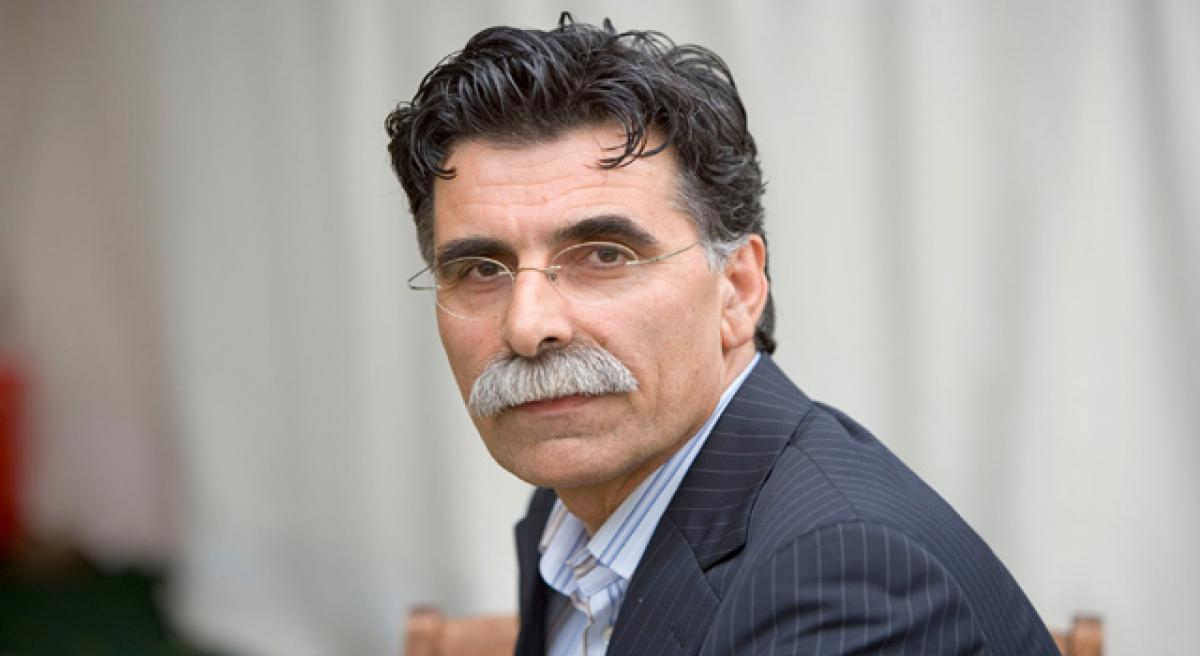

It is impossible to translate the Qur’an,” writes Kader Abdolah, at the start of his translation of the Qur’an. Prior to 9/11, Abdolah – then a popular émigré Iranian novelist in the Netherlands – had never even read the Qur’an, despite being raised in a Muslim family.

It is impossible to translate the Qur’an,” writes Kader Abdolah, at the start of his translation of the Qur’an. Prior to 9/11, Abdolah – then a popular émigré Iranian novelist in the Netherlands – had never even read the Qur’an, despite being raised in a Muslim family.

But with the fall of the twin towers came the necessity to do so; the new focus on Islamic extremism in the West meant that suddenly everyone had opinions about the book, although most had not read it. As a leading voice in the liberal Netherlands, Abdolah was expected to have a view.

When Abdolah read the Qur’an for the first time, he read it as a novelist: in it he recognised not only a text of faith, but also a work of literature of such elegance and style that it had the potential to speak to writers all over the world.

His Dutch translation was published in 2008 alongside The Messenger, a novelisation of Muhammad’s life intended to be read before tackling the holy book; the pair were immediate bestsellers. Eight years on, they can now be read in English, thanks to translators Nouri and Niusha Nighting.

In his most bold move, Abdolah adds an extra chapter to the Qur'an, in which Muhammad’s death is described So how does one tackle a task as weighty as translating a religious text? Something must be lost in the transition from Qur’anic Arabic to first Dutch and now English.

Abdolah laments the loss of “the beauty”, “the flavour, smell and feelings” of Muhammad’s language: in his introduction, he declares that he “knows nothing” and that he has made many mistakes. On first impression, these statements could suggest an understandable fear of backlash; Abdolah’s translation, which alters, cuts and adds to the original text, could appear sacrilegious.

However, Abdolah’s statements reflect not fear, but reverence – his respect for Muhammad’s original prose. Abdolah sees himself not as a translator but as an interpreter. Prioritising accessibility over religious mystery, Abdolah makes several weighty, and perhaps controversial, changes.

The original compilers of the Qur’an ordered the suras - or chapters – by length, making the text difficult to navigate, in order to reflect something of the unfathomable nature of Allah. Instead, Abdolah reorders the suras into a chronological order, allowing for Muhammad’s journey to be traced alongside the story explained in ‘The Messenger’.

In his most bold move, Abdolah also adds an extra sura – number 115 – in which Muhammad’s death is described. This addition, Abdolah explained in a recent interview with the Guardian, emphasises the importance of Muhammad in the Qur’an, a book usually attributed solely to Allah. Abdolah wished to bring into focus the “writer” of the Qur’an, a man who was a “dreamer” and “poet”. This addition, however, was also for Abdolah himself: “The last chapter is mine. Three people have written this book: Allah, Muhammad and Kader Abdolah.”

The frequent repetition, intended for the mostly illiterate audience of Muhammad’s time, is omitted in Abdolah’s translation. He also omits the Arabic alphabet letters that begin some of the suras, believed by some to be part of the Qur’an’s “sacred code”, a mathematical structure that proves it was not written by humans.

But if the Qur’an has lost anything in this rewriting, ‘The Messenger’ provides new context, enabling non-Muslim readers to approach the Qur’an with an otherwise impossible level of familiarity. The Messenger’s narrator is Zayd ibn Thalith, Muhammad’s adopted son, who sets out to chronicle the life of his father.

Zayd’s unique position in Muhammad’s life humanises him; we read of Muhammad’s illiteracy, his messy handwriting (“Hard to decipher. Like the scribbles of a child”) and his self-doubt when waiting to receive messages from Allah (“Who was Muhammad anyway? He was an orphan nobody wanted”). Muhammad becomes someone we can sympathise with and relate to.

The two books work in tandem, ‘The Messenger’ providing context and story; the Qur’an, poetry and mystery. But ‘The Messenger’ also allows for discussion of Muhammad’s more problematic behaviour – like the episode in the Qur’an where, at the height of his power, he burns the trees and fields of the Jews and exiles them from Medina. In The Messenger, Zayd speaks to a rabbi who angrily exclaims, “no prophet ever used as much violence as your Muhammad […] he ravished young women and thought up suras to justify eliminating us.”

As time passes, Muhammad the prophet becomes a politician, a warlord, a conqueror. Abdolah does not deny Muhammad’s violence, instead arguing that such violence is inherent to political leadership. “[Muhammad] has done the same thing many leaders do. The same as Bush, […] Obama, […] Churchill,” he told the Guardian. “Even if they are good people, they have [started] big, big wars and they have used violence.”

The controversies of Abdolah’s project cannot be denied and have not been: in many countries, publishers have published ‘The Messenger’ but rejected Abdolah’s Qur’an, for fear of a backlash. But considering the increase of Islamophobia in the West, there has arguably never been a more important time for moderate, analytical Islamic voices to be heard. Abdolah says he is “not afraid” of reprisals by extremists: “If those crazy people want to kill me, let them kill me. It is an honour to be killed for literature.”

Abdolah believes that the Qur’an, like other holy books, is not inherently violent or dangerous. “It is a dangerous book if you use it as [a set of] rules,” Abdolah says, but as literature, it is “beautiful.”

By: Claire Kohda Hazelton - The Guardian

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com