Live

- BJP backs LG's crackdown on illegal immigrants in Delhi

- AMR a global health threat, requires urgent action via one health approach: Anupriya Patel

- BJP planning big communal clash; we will expose them after Maha polls, says K’taka DyCM

- Sharad Pawar makes a soul-stirring plea 'to regain the glory of progressive Maharashtra'

- Seven soldiers killed in attack on Pak military camp in Balochistan

- ICC announces 2025 Men’s Champions Trophy tour to begin in Islamabad

- Americans increasingly vote along class lines, not racial ones: Report

- Chandrababu's brother Rammurthy Naidu Passes Away in Hyderabad

- Russia restricts enriched uranium exports to US

- South African President orders immediate closure of tuck shops linked to food poisoning cases

Just In

This is the story of Vasanti, the daughter of a milkman from a village in Maharashtra. Vasanti is 23, and in the final year of her Master of Management Studies program at a public university in Mumbai. She intends on a career in marketing and retail management.

This is the story of Vasanti, the daughter of a milkman from a village in Maharashtra. Vasanti is 23, and in the final year of her Master of Management Studies program at a public university in Mumbai. She intends on a career in marketing and retail management.

She spent 14 months working as an assistant marketing officer in a big company in Mumbai after her Bachelors, and before beginning her Masters’ program. Having studied in this field, she wanted to make doubly sure that this career path was her true choice. “Would I really like marketing? What are the line activities?

I introspected and found that, yes.” Her superiors were impressed with her, and promised to recommend her to any company she may choose to apply to after she finishes her Masters this year. “These are people who have seen me work with commitment and dedication,” she tells me.

Vasanti lives with her mother and father, her two younger sisters, and her grandmother in a small two-room house in central Mumbai where she grew up. In the family’s native Maharashtra village, her father completed the 10th standard and her mother the 8th in Marathi medium schools. “Our village has 45 houses; but 20 of them are shut.” Those people, like Vasanti’s parents, have migrated to Mumbai.

Vasanti’s family is of a caste whose traditional occupation is selling milk. Her uncle still has a dairy in the village and they visit him once a year. When her father was 16, he migrated to Mumbai to work with his older brother selling milk in the city. They collected milk every morning at a big dairy in Worli and delivered it to the customers’ homes.

When he came to the city “he saw educated people,” she said, and wished he himself could have been more educated. He married when he was 25 and his bride was 18. The next year Vasanti was born, and two more girls followed.

“They never regretted not having a son; they’ve always encouraged us to do everything a boy would do.” In a telling statement, she says, “He wants to complete his dreams through me.” Now the father is employed in a small firm working as a peon, earning Rs 8,500 a month.

Vasanti is more than self-supporting already. She saved for all her postgraduate fees from the year’s work as a marketing officer, and contributed money to her parents as well. And she still does. She earns currently by providing tuitions at her home to 17 children who live nearby.

Two batches of kids come each evening, from 6 to 7:30 and from 7:30 to 9, sitting with her in the only complete room in the house. The younger sisters study on the balcony, and the older people sit in the kitchen while lessons are going on. Vasanti earns Rs 11,500 a month this way.

She wants to continue her tutorial service even after she gets a professional job, expanding it with the help of a neighbor; she feels committed to the neighborhood children. Their parents are not much educated, and the kids need this kind of help with their studies.

She is not under pressure to marry soon, nor to have an arranged marriage; she may select her own partner. It’s possible she could be married to a boy of her caste, because some of them are also becoming educated now. She says that she has broad-minded parents, but that they come from a narrow-minded village.

She does not face restrictions on her movements, and is free to go out of town for exhibitions and school events, and to go out to parties with friends. In future, when she meets a possible marriage partner, she will insist on personal compatibility and a four to five month acquaintance, freely moving around town.

The boy should be on his own, earning, from a good family, a non-drinker, and living in Mumbai. He should support her working. She has a particular requirement: it must be understood that 50 percent of her income will always go to her parents.

This is clearly stated, in spite of her saying that she would gladly live in a joint family (with his parents). She expects to negotiate these matters directly with her husband-to-be, who will make them clear to his parents.

Vasanti is not the only working-class girl among my interviewees clearly headed for a middle-class career but she is one of the most remarkable.

Her father’s longings and regrets, as he carries out his family role while doing the job of a peon, are a poignant part of the story. Her parents’ unstinting encouragement and lack of restriction form part of the required context.

She also has strong advocacy from committed professors, and is a top student. She has translated herself into a global person, too, in her work experience with the company. One has to credit also the forwardness of the city of Mumbai.

Vasanti has ideals about her work and influence in the world. She feels committed to help educate poor children; and she insists that the company she works for must be an ethical one, with good business practices and good management. “You carry the image of your company, and it should bring pride to you,” she declares.

“I want her to do what I was never able to do!” We have now heard this remark, or something akin to it, from several fathers, across several different cities and sociocultural locations. In addition, these girls have surprised their parents, who had not previously had expectations that their daughter would make an amazing leap to another level. Education was important, but expectations were modest.

But the daughter reached a point of opportunity, and then convinced her parents to let her move ahead. The father’s humble job and the mother’s lack of education were not keeping them from investing their family’s hopes in their daughter; in fact, this humble background seemed to be the very cause for their doing so, when that daughter was their firstborn child. It seemed that they did not regret the firstborn not being a son; it was rather as though it was seen as a special, unique blessing that their first child was a talented, energetic, and an intelligent girl.

A young woman of very modest background who is the eldest child of her parents may become the standard bearer for her entire natal family. The expectations placed upon her tend to grow as her accomplishments grow. She is to succeed and be a source of pride as well as income for her family.

In families with no son, the daughter plans to continue to support parents in old age; in families with younger siblings, she intends to help to see them educated. If there is a younger son, the daughter is expected to become self-supporting but not support her parents later on. She is not to expect a dowry; her earning capacity is expected to suffice.

These are challenging, sometimes even daunting expectations, yet their burdensomeness is outweighed in the outlook of my subjects by their own transformation into something much bigger within their family circle than what a woman used to be. Another girl in my study, who is the only child of her parents, says, “I am their son.”

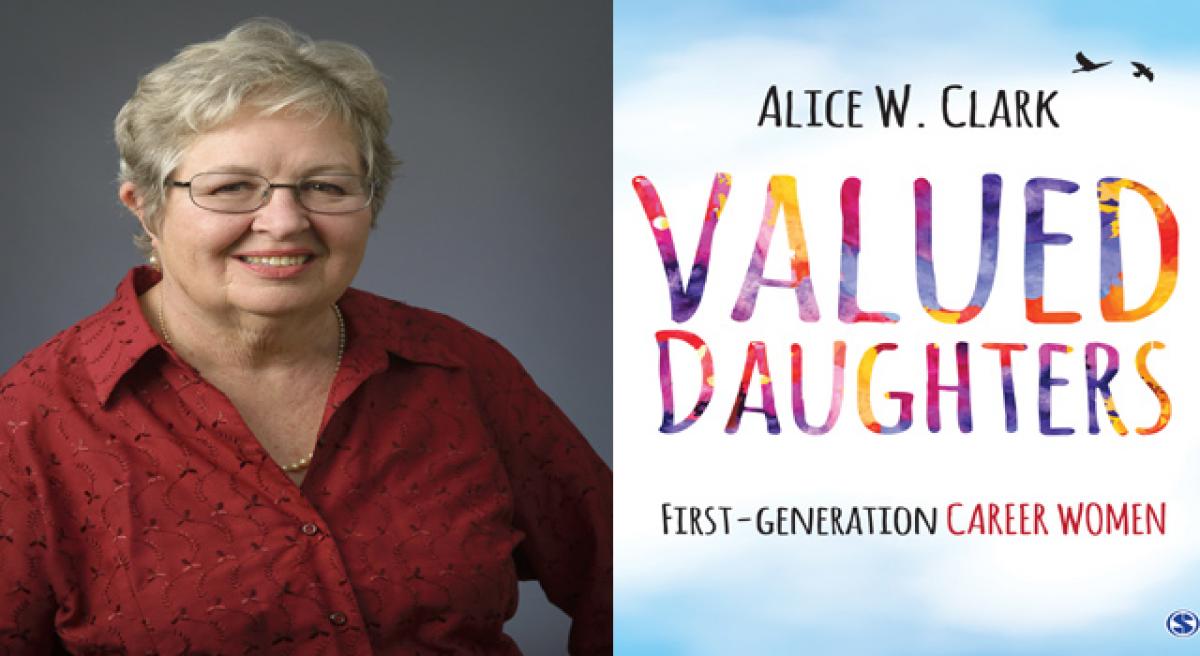

(From Valued Daughters: First Generation Career Women by Alice W. Clark; published by Sage Publications; `595)

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com