Live

- Thanks to Centre, AP on fast-track mode

- First Impressions and Unboxing of the MacBook Pro M4: A Powerhouse for Professionals and Creators

- China Gears Up for Potential Trade War Amid Trump’s Tariff Threats

- Small Farmers Gain Less by Selling to Supermarkets: Study Reveals

- Why Despite the Controversy, America Is Anticipating the Mike Tyson vs. Jake Paul Fight

- Sanju Samson and Tilak Varma Shine: Record-Breaking Feats in 4th T20I Against South Africa

- India Urges $1.3 Trillion Annual Climate Support for Developing Nations

- Bad air: 106 shuttle buses, 60 extra Metro trips planned to make Delhiites give up cars

- WHO reports declining monkeypox cases in Congo

- CM Attends Kotideepotsavam on Kartika Purnima

Just In

The nirbandha or betrothal ceremony took place in a house teeming with relatives. While Dr Mansingh and Sonal’s father took a ritual vow to get Sonal and Lalit married to each other, all Sonal remembers of the ceremony is a little exchange with her mother-in-law.

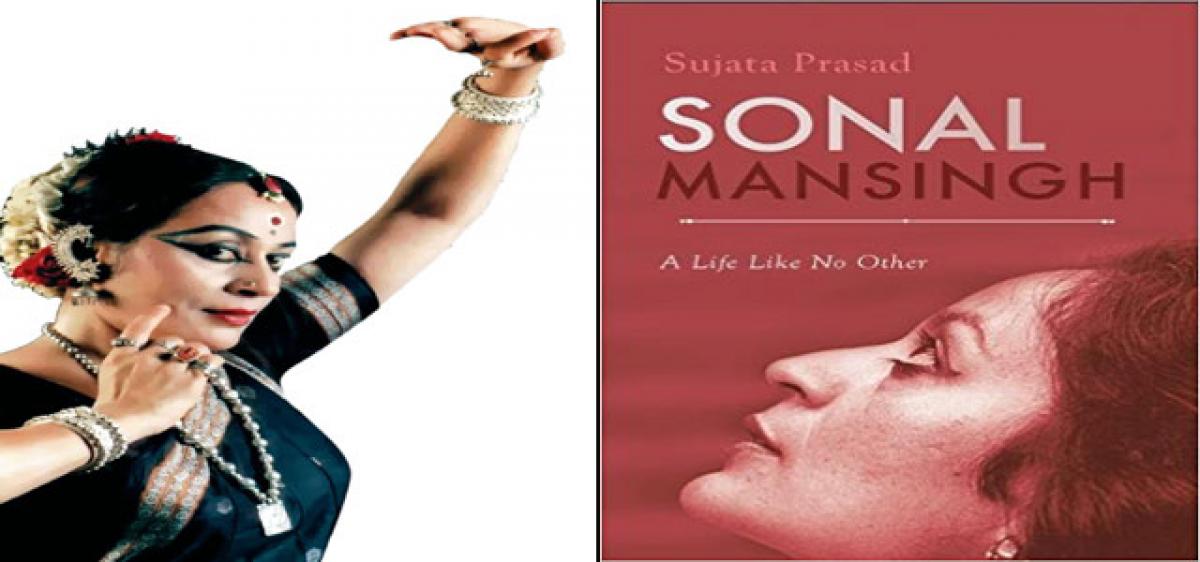

The biography of Sonal Mansingh by Sujata Prasad is an effort to understand the woman and the artist behind the celebrated personality

The nirbandha or betrothal ceremony took place in a house teeming with relatives. While Dr Mansingh and Sonal’s father took a ritual vow to get Sonal and Lalit married to each other, all Sonal remembers of the ceremony is a little exchange with her mother-in-law.

‘You must have children,’ said the matriarch fixing her with a gimlet eye. ‘And they must speak Oriya,’ was her next commandment. Sonal’s response was quick and sharp. ‘No, they will speak both Gujarati and Oriya,’ she retorted, ignoring her mother—in—law’s giant eye-roll.

Drawn to the ordinariness of Lalit’s home but a little awkward initially, Sonal prepared herself for some amount of existential dissonance or revelatory close-ups that could be unsettling, but Lalit’s father and siblings, brother Labanyendu, sisters Nivedita and Sanghamitra, were exceptionally warm.

Their intimate conversations and playful bonhomie gave her a sense of belonging. Sexy, lively, even a little audacious, Sonal in turn wowed everyone. Reassured by what he saw, her father went back to Bombay. Sonal stayed back for two weeks at Dr Mansingh’s request.

The time spent in Cuttack was to change the course of her life as a dancer. She developed a special closeness to Dr Mansingh, spending hours in his book-lined study-cum-bedroom trying to understand his artistic and literary sensibility. She was captivated by his intellectual heft and charisma.

A leading educationist, credited with introducing the works of Shakespeare in Oriya literature, he was also known as Premika Kabi or a romantic poet. His first collection of poems, Dhoop, had made him a household name.

Many of his poems were set to music and were part of the Odissi dance repertory. There was another facet of Dr Mansingh that has gone largely unreported. He was part of the post-1950s collective, a group of renowned Odissi gurus like Kalicharan Patnaik, Mahadev Rout, Raghu Datta, Pankaj Charan Das, Debaprasad Das, Kelucharan Mohapatra and Mayadhar Raut, that was trying to engage with the tumultuous history of Odissi and the movement to rebuild it from its vestigial remnants.

In the early 1950s, the Odissi repertory was really limited. When the first performance of Odissi was organized in Cuttack in 1953, it was based on a single composition of less than fifteen minutes. The reconstruction or revival involved study of ancient literary texts, and the dance movements reflected in bas-relief in historic temples of Parasurameswara, Brahmeswara and Konark.

Starting from some of the earliest temples of the sixth century, there was barely a temple in Orissa where dance was not depicted in sculpture. The Utkal Nrutya Sangeet Natya Kala Parishad that was later converted into the State Sangeet Natak Akademi provided the much-needed official support for research and development of Odissi dance.

The recognition of Odissi as a classical dance form came in 1958. Described as the ‘Odra-Magadhi’ style of dance in the Natyashastra, sculptural evidence seems to indicate that Odissi was perhaps the oldest surviving dance form in India. Over the centuries, three distinct styles of the dance emerged.

The mahari tradition that flourished in temples is attributed to King Chodaganga Dev who built the Jagannath temple in Puri. It ended with the recent death of Shashimani, the last living mahari at the temple.

Married to the deity when she was barely seven, she danced inside the sanctum sanctorum morning and night to the lyrics of Jayadeva’s ashtapadis. However, with the exception of Pankaj Charan Das, none of the other eminent Odissi gurus owed the genesis of their dance-acculturation to the mahari tradition.

The nartaki tradition of somewhat lascivious dance forms developed in the royal courts. It was at the centre of the anti-nautch movement in the early years of the twentieth century.

The gotipua tradition, represented by pre-pubescent boys in akharas who were trained to dance, successfully weathered the anti-nautch blizzard. Dressed and made-up like girls, young boys danced outside temples to devotional poems of Vaishnava poets using simple footwork and acrobatic and tantric yogasanas.

Even while being a male dance, gotipua was not completely testosterone—driven and included lasya or feminine movements. This tradition remained part of the Odissi DNA. Most Odissi gurus were trained gotipua dancers who were trying to walk the fine line between classical and neo-classical dance.

Laxmipriya Mohapatra, wife of Sonal’s guru, was the first woman to perform Odissi on stage, ending the traditional male hegemony over the dance form.

Overriding his wife’s protests, Dr Mansingh wasted no time in taking Sonal to the Kala Bikash Kendra, an Odissi dance school started by Babulal Doshi in 1952, where Odissi guru Kelucharan Mohapatra was a revered teacher, with disciples of the stature of Sanjukta Panigrahi, Kumkum Das and Meenakshi Nanda. Sonal recalls that precious moment.

Dr Mansingh took me to Guruji and ordered, ‘Ai Kelu, ayee mor bau Sonal, tame taku naach sikhaibo. ’ (‘Kelu, this is my daughter-in-law Sonal, you will teach her dance.’) And that’s how my journey in Odissi began.

Extracted with permission from Penguin.

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com