Live

- Ticket distribution: AAP's public feedback on 70 seats

- Since YSRCP Boycotting Assembly Session: Alliance MLAs told to play Opposition role too

- Reliance invests big in AP

- 2024 on track to be hottest year on record

- PM Modi’s visit to Solapur: Women applaud ‘Double-Engine’ government’s initiatives

- Nagarkurnool MLA Dr. Kuchukulla Rajesh Reddy Campaigning in Maharashtra Elections

- Wife Kills Husband with Her Lover: Details of Veldanda Murder Case Revealed by SP Gaikwad

- Strict Action on Violations of Food Rights: Telangana Food Commission Chairman Goli Srinivas Reddy

- Smooth Conduct of Group-3 Exams with Strict Security Measures: Collector Badavath Santosh

- Delhi HC orders cancellation of LOC issued against Ashneer Grover, wife

Just In

Perhaps Vivekananda now envisioned a different future forNivedita. With her sincerity and commitment never in question,her ability to grasp his ideas, her eloquent prose, her gift of public speaking, the ease with which she could mingle with the Europeansand act as a bridge with the Brahmo elite in Calcutta society werewell appreciated by Swamiji.

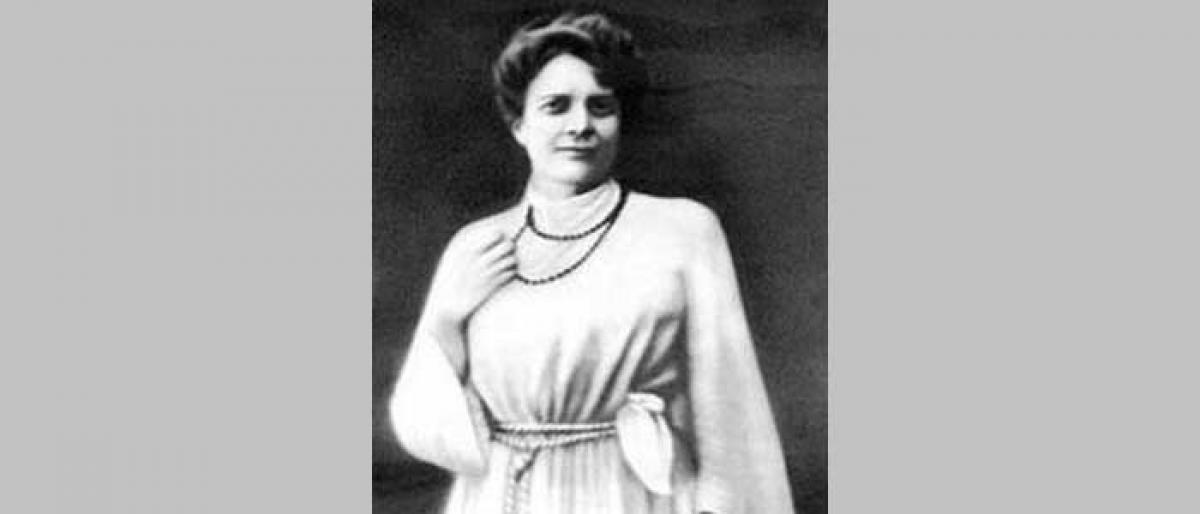

Margot: Sister Nivedita of Swami Vivekananda’ by Reba Som reveals the feisty, irrepressible spirit behind one of India’s greatest friends – Sister Nivedita

Perhaps Vivekananda now envisioned a different future forNivedita. With her sincerity and commitment never in question,her ability to grasp his ideas, her eloquent prose, her gift of public speaking, the ease with which she could mingle with the Europeansand act as a bridge with the Brahmo elite in Calcutta society werewell appreciated by Swamiji.

As early as 17 February 1896, in a letterto his benefactor and supporter Alasinga Perumal, Vivekanandahad expressed his dream ‘to put the Hindu ideas into English and then make out of dry philosophy and intricate mythology andqueer startling psychology a religion, which shall be easy, simple,popular, and at the same time meet the requirements of the highest ‘minds’. He now found Nivedita to be the right person to carry out his dream. Already, a month back, she had created waves with herspeech on Kali to packed audiences at Calcutta’s Albert Hall.

The invitation to Nivedita to speak on Kali on 13 February 1899had not only taken her by surprise but also ‘shocked’ the educatedelite of Calcutta to whom Kali worship remained associated with thetemple practices of daily goat slaughter. Indeed no one was prepared to chair the meeting after the Principal of Vidyasagar College,N. Ghosh, who had previously agreed, backed out at the last instance. Nivedita, however, was not to be deterred and decidedto go ahead nonetheless.

Vivekananda, who had welcomed the opportunity so that he could get even with his detractors, who had criticized his Kali worship despite his belief in monotheism or Advaita, was convinced that a talk on Kali by his foreign disciple, anda woman at that, would be a befitting reply. He could never forget how his beloved Dakshineswar Kali temple continued to remainout of bounds for him on the specific instructions of the templeauthorities.

Vivekananda took on the challenge by thoroughlybriefing Nivedita on the subject and reading through her preparedspeech. Curiosity about her andwhat she would present resulted inlarge numbers turning up. Dr Mahendranath Sarkar, well—knownphysician, agreed to chair the meeting but being avidly opposed to idol worship, he raised provocative questions about why such regressive moves to worship the Kali were needed, leading to a fracas with a member of the audience calling him ‘an old devil’. It required the grace of Nivedita to restore decorum and proceed with a well thought—out lecture, in which she not only voiced her guru’s ideas but also couched them in her own world view.

Beginning with a disclaimer that without a knowledge of Sanskrit or Indian history she was hardly suited to lecture on Kali, Nivedita declared her right as an English woman to publicly regret the vilification carried on by her countrymen of this religious idea. She said that instead it could be approached as a subject with a certain freshness of view, and by drawing comparisons with another faith.

She went on to speak of the three aspects of the mother goddess—Durga, Jagadhatri and Kali—as embodiments of power and energy evolving to the final incarnation as Kali or Death bringing the ultimate freedom. Bluntly, she went on to say, “Religion is not something made for gentlehood . . . to refine is to emasculate it . . . God gave life, true.

But he also kills. Let us face also and just as willingly, the terrible, the ugly, the hard.’ The depiction of the naked and violent Kali went against the accepted notion of womanliness associated with the Hindu woman. But as Nivedita explained, since Kali depicted maya, which was unreal, she had to be painted as the ideal non-woman. Her real existence lay in Brahman and by going beyond her present form, she had to be realized as Brahmamayi (pervaded, interpenetrated, overlapped and full of Brahman), so eloquently sung by the devotee 'Ramprasad.

The resounding success of the lecture was evident in favourable press reviews. A correspondent in the Indian Mirror was to write, ‘It was a novel thing to hear an English lady

speaking in support of Kali—worship . . . and her explanation was a most rational and philosophical one . . . free from orthodoxy and bigotry.’ Nivedita was relieved since she knew how ignorant even the educatedEnglishwere about the symbolism in the Hindu religion. Indeed, she was to write that many thought that Kali was a real woman who had killed her husband. Her King ‘was greatly pleased about the lecture’, and the invitation that followed soon after, for her to speak on Kali at the Kalighat temple itself seemed ‘the greatest blow that could be struck against exclusiveness’.

At the second Kali lecture, which Nivedita delivered at the famous Kali temple of Calcutta in Kalighat on 29 May 1899, Vivekananda was asked to preside but declined. Prompted by Sarada Devi, he came to Nivedita the previous morning at six and stayed for a couple of hours, briefing her over cups of tea and a smoke.

He had already given strict orders about the lecture, where the audience would not be given chairs but would be seated instead on the floor around Nivedita, who would be on the steps with a few guests. He reminded her that she would also have to ensure that the European and the Brahmo guests removed their shoes and hats. While discussing the coming event with Nivedita, Vivekananda confessed, ‘How I used to hate Kali and all her ways.’

It was a six-year-old fight with his guru Ramakrishna, whom he often thought was ‘simply a brain—sick baby, always seeing visions and things – I hated it—but I had to accept her too!’ When Nivedita pressed him to reveal what had led to a change in mind, he merely said that family misfortunes had made him turn to Kali and he had been enslaved. But the actual details ‘will die with me’. But in the end, he was convinced that universal oneness was manifest in Brahman as well as in the gods. And there was no contradiction there. He cautioned Nivedita, ‘But these things must never be told to anyone—never.’

The second Kali lecture was the same in the substance as the previous one at Albert Hall but it was followed by some explanations she offered to questions that were raised. Drawing a comparison between the fearful image of Kali and the sombre, nearly sinister, visage of Mother Mary in Byzantine icon paintings, Nivedita spoke of the need to recognize that divinity lay beyond form.

Extracted with permission from Penguin Random House India.

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com