Live

- Cancel panchayat elections in Punjab: Sukhbir Badal

- IIT Madras’ new quantitative research lab to boost AI research in financial markets

- ED raids Vatika Limited in Delhi and Gurugram in money laundering case

- International equestrian returns to India after 14 years with AEF Cup Youth in Bengaluru

- U&i Unveils Feature-Rich Neckband, TWS, Powerbank, and Speaker: Idle Gifting Options for the Festive Season

- Studies at the Local Level Essential for the Preservation of the Western Ghats --Dr. Ullas Karanth

- US presidential election: Trump and Harris aiming to leverage PM Modi's great connect with diaspora, believes former FS

- Indian MF industry's average asset under management up 2.97 pc in Sep

- 28 killed in Israeli airstrike on school in Gaza

- Sports Ministry invites comments on Draft National Sports Governance Bill 2024

Just In

Writing On The Mess That Is War, we don’t even fully experience their reality, because the spectacle of the war on terror screens that greater horror of the other war from our eyes

…we don’t even fully experience their reality, because the spectacle of the war on terror screens that greater horror of the other war from our eyes

This vivid account of a shootout in Iraq involving American soldiers and a family of eight, including six children, in strife-torn Iraq exposes the stark truth of war – the fundamental inequality of power is a wall that cannot be breached without violence even though war itself “is an elaborate and expensive distraction that hides from us the real crime”

Let me recount a story told by a photographer for Getty Images in a book called Reporting Iraq. The photographer, Chris Hondros, had accompanied a U.S. combat unit, in January 2005, to Tal Afar in the north of Iraq. One night after the curfew, the unit was out on a patrol when a car turned onto the darkened boulevard and came toward them. Hondros said:

Let me recount a story told by a photographer for Getty Images in a book called Reporting Iraq. The photographer, Chris Hondros, had accompanied a U.S. combat unit, in January 2005, to Tal Afar in the north of Iraq. One night after the curfew, the unit was out on a patrol when a car turned onto the darkened boulevard and came toward them. Hondros said:

I had a feeling the situation was going to end up badly. So I moved over to the side, because I feared some warning shots would be fired. The car kept coming. It was dark. Sure enough, somebody fired some warning shots, the car kept coming. And then they fired into the car. And it limped into the intersection, clearly no longer under its own power, just on momentum, and gently came to rest on a curb. I was kind of paralyzed, and then slowly walked to the car and, sure enough, I hear children’s voices inside the car, and I knew it was a family.

The doors opened; the back doors opened, and kids just tumble out of the car, one after one after one—six in all. One was shot to the abdomen, though we didn’t realize he was shot at the time, though he was bleeding profusely and as soon as he dropped, there was blood in the street. The soldiers realized it was a civilian car. They ran and grabbed all the kids and ran them to the sidewalk. In the front seat, what ended up being the parents were killed, riddled with bullets, instantly dead. The children in the back were, incredibly enough, okay, except for the one kid who was winged in the abdomen.

This is difficult to read, but it needs to be read because it is a story about the disaster of war. The shock of the shooting is experienced by the reader in slow motion. The epiphany I have on reading it, as if I were seeing it on a screen, on the grainy film the blurry movement of the car and the soldiers, hollows out the moment and makes it expand. My epiphany is that this is forever the truth of war: the grave injustice of any war. …

Hondros goes on to tell us other things: the boy who had been shot in the stomach was flown to Boston for treatment; the boy told the Americans that the family had been out visiting and were trying to get home. And then, as if to chastise me for talking glibly about inevitable violence and for having mocked easy liberal pretensions about multiculturalism, there is in the photographer’s testimony a little lesson in cultural awareness:

It was a little bit after the curfew, but time is never a precise thing to Iraqis—it’s not like this German, iron-clad, six-to-one curfew. It’s more like, all right, you’re not supposed to be driving around at night. Generally speaking, you could be out on the roads after six o’clock and nothing would happen to you. They were just trying to hustle and get home, and they’re driving along, and all of a sudden they hear shots. They don’t see—it’s dark—they don’t see camouflaged soldiers in the dark in front of them. They just hear shots. Now, when you’re in a car driving around in Iraq and you hear shots, your first instinct is to speed up, because either someone’s shooting at you for some reason or somebody’s about to get into a battle nearby. Either way, you don’t want to be around there; you want to get out of there. And then, the headlight range—by the time they actually get into the region of your headlights, forget it, that’s way too close, they’re already engaging you by that point, shooting you up by that point. So that’s why they didn’t stop.

Such luck, such sorrow. In the end, this is what it comes down to: who will teach one to be modern, who will teach the other to be human? This is the central dilemma in the so-called clash of civilizations. Or, so it seems, in my dark despair. A car on a road at night with a man trying to drive close enough to be able to say “Sir, we are just a car with a family driving home.” And on the other side a group of soldiers holding their guns as if to say “You’re gonna die, motherfucker!” The soldiers wondering whether they too are going to die, and then finding the answer very close to them, on the little curve of metal under their tense fingers. It is often just that easy. Because this is what Hondros says:

Almost every soldier in Iraq has been involved in some sort of incident like that or another, I would say. Their attitude about it was grim, but it wasn’t the end of their world. It was, “Well, kind of wished they’d stopped. We fired warning shots. Damn, I don’t know why the hell they didn’t stop. What’re you doing later, you want to play Nintendo? Okay.” Just a day’s work for them. That stuff happens in Iraq a lot. That’s why it’s such a damn mess, because almost everybody’s had something like that happen to them at the hands of U.S. soldiers. They hate them. …

I have quoted at length from Hondros’s account of the incident at Tal Afar because I am held by the pathos of the images and the story of how they came to be. … In some measure, we don’t really see the images that Hondros is talking about, and we don’t even fully experience their reality, because the spectacle of the war on terror screens that greater horror of the other war from our eyes. … The slow, calm procedure of law hides from our view the brutality of the state and the horror of war.

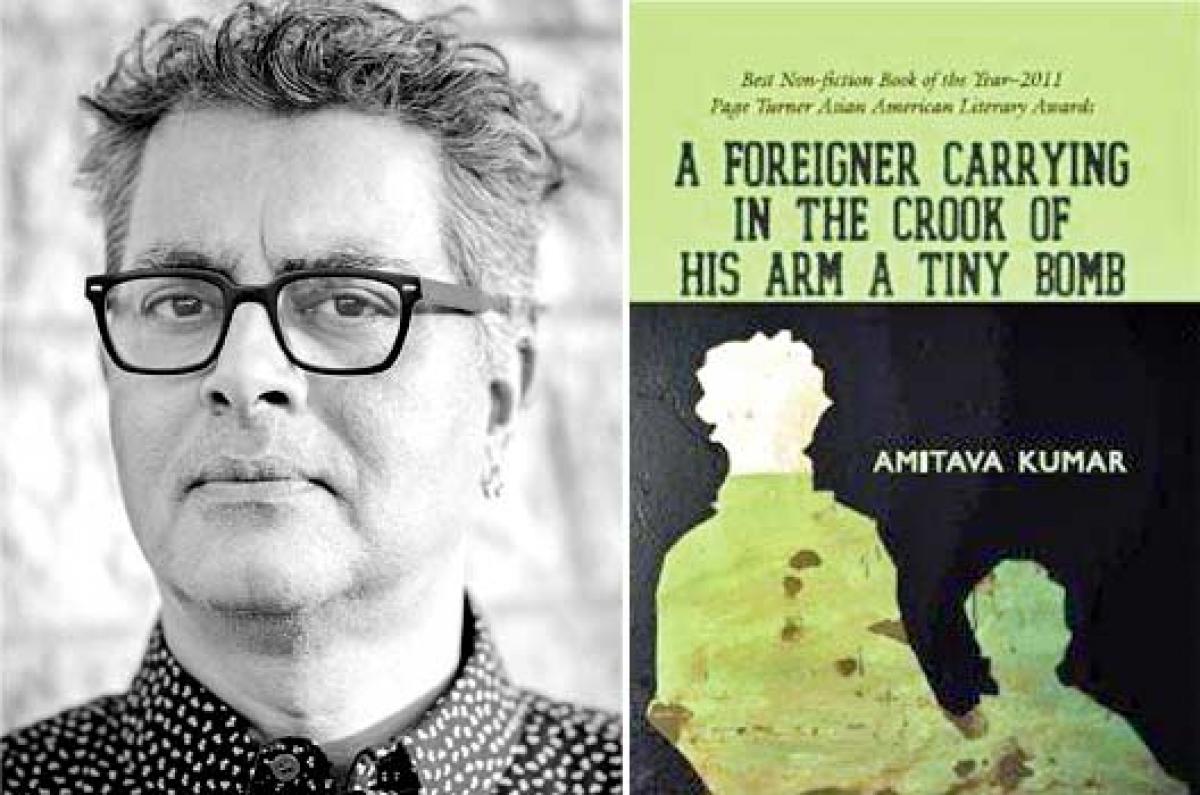

( From: A Foreigner Carrying In The Crook of His Arm A Tiny Bomb, by Amitava Kumar; Published by Pan Macmillan; `399.)

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com