Live

- Latvia to ban cellphones in elementary schools

- MP: Bilkhiriya Kalan residents reap benefits of Jal Jeevan Mission scheme

- MP govt preparing training guide for growth of school children

- India bids tearful adieu to icon Ratan Tata, thousands join his final journey

- A fast-paced flick of the hunter and the hunted

- Prasanth Varma unleashes first female Indian superhero from PVCU 'Mahakali'

- Rana launches FL &title of 'Khel Khatam Darwajaa Bandh'

- RK films acquires Telugu rights of 'Jhansi IPS'

- 'The Great Pre Wedding Show' launched traditionally by Rana Daggubati

- Odisha: Guidelines issued for Shahid Madho Singh Haath Kharcha Yojana

Just In

More and more writers return the Sahitya Akademi award, others vehemently protest the killings of writers and the religious intolerance they perceive as government approved, while few others stay neutral – is the scenario leading to what Salman Rushdie, once referred to as cultural emergency?

More and more writers return the Sahitya Akademi award, others vehemently protest the killings of writers and the religious intolerance they perceive as government approved, while few others stay neutral – is the scenario leading to what Salman Rushdie, once referred to as cultural emergency?

It was May 30, 1919, after General Dyer’s Jalianwalla Bagh Massacre; when Ravindranath Tagore decided to return his Knighthood. He gave away the ‘Sir’ title to the British, saying, “The time has come when badges of honour make our shame glaring in the incongruous context of humiliation…”

Not long ago, when the country was in the throes of Emergency imposed by the then Congress regime under the captainship of Indira Gandhi, several writers renounced their State sponsored awards. The Emergency announced on June 26, 1975, was an unpleasant surprise and it is beyond comprehension the kind of censorship that was slapped on the written word. In such a context there were hardly any voices of dissent, for the few who talked against it were jailed. None spoke, until at the annual Marathi Sahitya Sammelan, feminist, socialist writer, Durga Bhagwat took to stage and slammed the Emergency. According to a feature on the subject on Indian Express website, Bhagwat’s fearless act encouraged the city’s literati and artistes, and triggered a movement against Emergency. She was later arrested. Author Indumati Kelkar, a follower of Ram Manohar Lohia and his biographer, Hindi writer Murli Manohar Prasad Singh, poet Girdhar Rathi and Vaidya Nath Mishra, famous as Nagarjun, expressed their protest, and were put behind bars.

Not long ago, when the country was in the throes of Emergency imposed by the then Congress regime under the captainship of Indira Gandhi, several writers renounced their State sponsored awards. The Emergency announced on June 26, 1975, was an unpleasant surprise and it is beyond comprehension the kind of censorship that was slapped on the written word. In such a context there were hardly any voices of dissent, for the few who talked against it were jailed. None spoke, until at the annual Marathi Sahitya Sammelan, feminist, socialist writer, Durga Bhagwat took to stage and slammed the Emergency. According to a feature on the subject on Indian Express website, Bhagwat’s fearless act encouraged the city’s literati and artistes, and triggered a movement against Emergency. She was later arrested. Author Indumati Kelkar, a follower of Ram Manohar Lohia and his biographer, Hindi writer Murli Manohar Prasad Singh, poet Girdhar Rathi and Vaidya Nath Mishra, famous as Nagarjun, expressed their protest, and were put behind bars.

The current scenario where award-winning writers are giving away their Sahitya Akademi awards in protest of the killing of eminent thinker, writer Kalburgi (who was also an important member of Sahitya Akademi), Marathi writer Narendra Dhabolkar and Gobind Pansare, and the apathy of the Akademi in not reacting to the killings, is creating a lot of debate in the literary circles.

Salman Rushdie who had on earlier occasions warned India of cultural emergency, tweeted - I support #Nayantara Sahgal and the many other writers protesting to the Sahitya Akademi. Alarming times for free expression in India (sic).

These are not the voices that have emerged out of the blue. The dissent has been brewing. And the recent incidents, including the Dadri lynching only strengthened the voices as more and more writers are joining the protest by the day. While some choose to return the award, the others opine that since the Akademi is an independent body, they would rather let their protest be known than return the Sahitya Akademi award. There have also been voices that blame the authors as being Left-oriented intellectuals or plain publicity mongers.

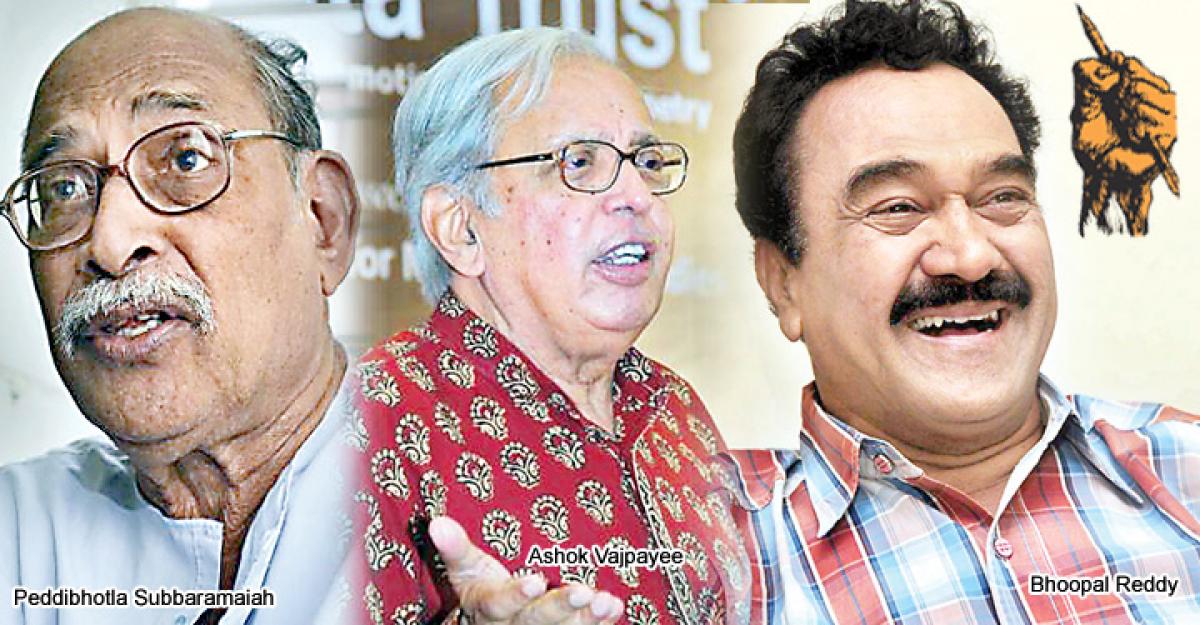

“The fact that these incidents have not elicited any response either from the Akademi or the Prime Minister has only strengthened my resolve,” shares Bhoopal Reddy, who is the first Telugu writer to have joined the bandwagon, and is not concerned with allegations. Another Telugu writer, Katyayani Vidmahe, who too has returned the award says, “We protest the danger that threatens the democratic fabric of our country. One can critique an author’s work, but killing him is something we have never seen in our country before. To protest this dangerous trend, I need not belong to a particular ideology.”

“There is no use of just protesting. Who will hear us? We need to return the awards that may ruffle some feathers and coax them into taking some action,” say the members of revolutionary writers association, VIRASAM, in an open letter.

“I have lost trust in the Akademi. How can you say the Akademi is not related to government – it is after all run with the funds and support of the government,” adds Bhoopal Reddy, expressing his view that more writers from the Telugu land will join them very soon.

At the other end of the spectrum are the writers who disagree with this method of protest. One of them, Vikram Sampath in his article in Live Mint, says, “Writers like me, who disagree with this mode of protest and expressed our opinion on social media were at the receiving end of reverse “liberal trolls”, branded as communal, fascist and bootlickers of the “despotic, intolerant and authoritarian” Modi regime. These epithets were hurled at us, ironically, in support of freedom of expression. I was reminded of what Bertrand Russell wrote in Unpopular Essays, “Collective fear stimulates herd instinct, and tends to produce ferocity toward those who are not regarded as members of the herd.” And writers deny the allegation.

Ashok Vajpayee, one of the first writers to join the movement said in a statement - “None of us belong to any political party though we have views on politics. But we are extremely worried at the way the India polity is moving. All spaces of liberal values and thought, all locations of dissent and dialogue, all attempts at sanity and mutual trust are under assault almost on a daily basis. All kinds and forms of violence, whether religious and communal, consumerist and globalising, caste-based and cultural, social and domestic, are on the upswing. An ethos of bans, suspicions, hurt feelings is being promoted by many forces that are active and have been emboldened by powers that be, without the slightest fear of law. Democratic rights of expression, faith, privacy etc. are being looked down upon and curbed or disrupted without provocation or fault.”

Apparently, writers are terrified at the series of incidents that threaten the plural identity of the country.

“There is growing intolerance in the country. The irresponsible comments from MPs, MLAs and heads of regional parties are only stoking the flames that are extremely detrimental to the plural nature of our nation. Religion is a sensitive issue and what we see around us is a dangerous tendency. And the government instead of warning and taking action on perpetrators of violence is seemingly endorsing the tendency. If this continues there will even be street fights and going forward, this may lead to civil war,” shares Telugu writer, Sahitya Akademi awardee, Peddibhotla Subbaramaiah.

He, along with ten other writers released a statement earlier condemning the culture of intolerance. Even though, they decided against returning the awards, they empathise with the ones who have done so.

“We did not want to return the awards as a mark of respect for the organisation, but that doesn’t discount the fact that the writers, who have been killed were recipients of the award, and were an important part of the Akademi, which is after all funded by the government. And, to let such acts go un-protested will only lead to more such incidents. When a great poet like Nayantara Sehgal has returned the award, it must have been because of the extent of hurt she had felt – but she was reduced to mockery by a few sections. The secular fabric of our country is being mocked by calling it Pseudo-Secularism. A great singer was disallowed from singing. Government is being led by religious forces. We need to stop this immediately,” he adds.

As emotions run high, more and more writers return the award, several others choose not to, and a lot many debates rage on the social media and beyond; closer home, writers like Peddibhotla and Kethu Viswanatha Reddy decided to protest, but not resort to returning the award. “We have been in the process of collecting opinions to come to a decision. Since that is taking some time, I decided to return my award. It is a personal decision; there may be others who would like to protest in a different way. That doesn’t make it less important,” shares Katyayani. For many of the writers, October 23, when Sahitya Akademi has convened a meeting, is the D-day. And their plan of action will be based on the reaction of the Akademi.

More importantly, the literary circles of India, who can be percevied as the voices of common man, in unison, hope for response and action from the Akademi and the government, failing which, the voices may only grow stronger.

By Rajeshwari Kalyanam

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com