Live

- Harassment, disrespect, absent amenities: Women medical staff in Pakistan face same harrowing issues as Indian counterparts

- Kerala HRC recommends banning shoots in government hospitals

- Assam govt only focuses on divisive politics: Congress MP Syed Naseer Hussain

- Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi arrives, to meet PM Modi on Monday

- 55 injured in bus-truck collision in Iran

- Gurugram: Former MLA’s wife & son join BJP ahead of Haryana polls

- Suspected Mpox case under investigation, patient isolated: Centre

- Supreme Court to resume hearing RG Kar Medical College suo moto case on Monday

- Crucial India-Gulf Cooperation Council meeting in Riyadh on Monday

- Stalin appeals to Tamil diaspora to visit mother state once a year

Just In

There was a funny smell in the room. No one said anything about it, but I could tell from Rustom uncle’s nose that he didn’t like it. He was sitting opposite me. His nostrils were permanently hitched up like ganga’s sari when she swept our floor. But he didn’t use a handkerchief. Nor did anyone else in the room. I suppose it had something to do with the occasion.

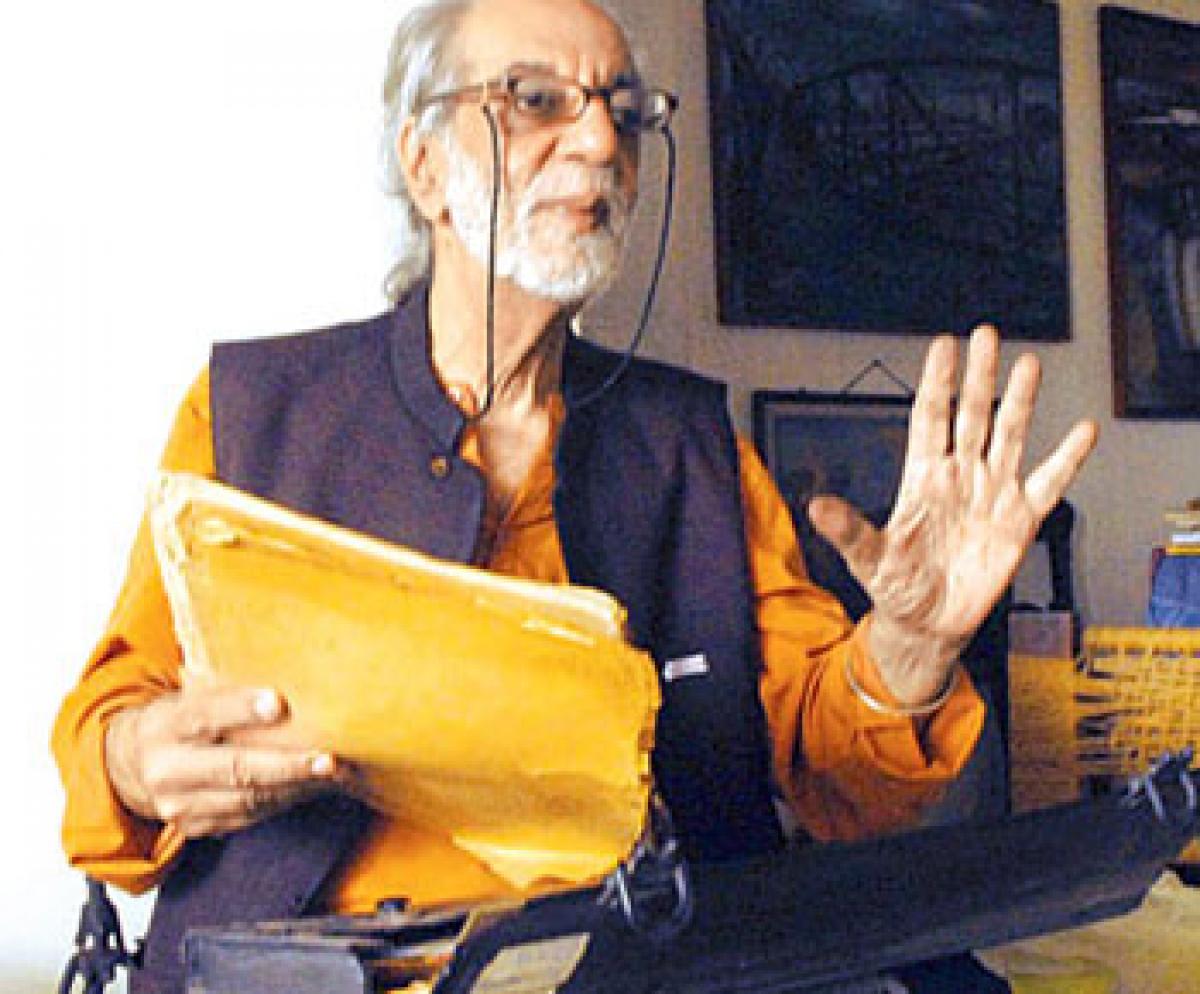

Adil Jussawalla, the Sahitya Akademi award winning writer, columnist and literary editor to various magazines and newspaper was also greatly admired poet.

Adil Jussawalla, the Sahitya Akademi award winning writer, columnist and literary editor to various magazines and newspaper was also greatly admired poet.

‘I dreamt a horse fell from the sky’ is an anthology of his poems, fiction and non-fiction writing. Here’s a small extract from his unfinished novel…

There was a funny smell in the room. No one said anything about it, but I could tell from Rustom uncle’s nose that he didn’t like it. He was sitting opposite me.

His nostrils were permanently hitched up like ganga’s sari when she swept our floor. But he didn’t use a handkerchief. Nor did anyone else in the room. I suppose it had something to do with the occasion.

We were in the Blue Room. It was filled with blue Chinese vases and blue peacocks. They had put a round tray on a carved chest and on the tray a small blue dish with a flame burning in it. The blue dish had a blue cover. Smoke poured out of an urn-loban, they called it - and rose past a tall portrait.

Hair and flesh — that was the cause of the smell. I realized that when I saw a group talking in low tones and throwing looks at the door of the room where it had happened. The door had a lock on it. I got bored after I discovered this and began swinging my legs which barely reached the floor. I was seven years old but short for my age. One look from Rustom uncle told me this wasn’t an occasion for swinging legs.

I had warned them it would happen. I had warned them. I can still hear my mother shouting ‘No!’ when I first told her, and feel the air from Rustom uncle’s hand which missed me and hit my Mecanno box, scattering some of the pieces in it.

I had known that Sheroo aunty, who was such a kind person and who smelt of old satis and rosewater, who dressed in baggy brocaded blouses and plain saris, was losing her mind. One day I had caught her praying before the urn, the loban: ‘God, send me to my father. God, give my father back to me.’ She had clutched her hair, fallen on her bed, and sobbed.

I had been sent with a note asking her to lend my mother a recipe book and I had walked into her room. The doors of her house were always open to us. I thought that was because soon after Daddy died, her husband had left her. No one mentioned his name though he was called ]al.

She also treated many other children as her own and would let us play in her house, even in the Blue Room. But we were afraid of her too because sometimes she would let us play, at other times lose her temper and drive us out.

That day, when she caught me watching her, she sprang from her bed, ran to me and hugged me. When she began to laugh, I, not liking the smell of her sari any more, squirmed away from her.

‘But Rumi, wait for the recipe book. Wait.’ She had snatched the note from me and read it. It was in Gujarati but she tried to speak to me in English. I suppose it was because I was going to an English school. She began opening her many wardrobes distractedly.

They were filled with clothes she never wore. I caught a glimpse of a deep purple sari shimmering with sequins, a red sari... She shut two of the wardrobes and began looking under her bed, saying, ‘Recipe book, recipe book.’ Then she disappeared through a bead curtain and returned with five or six small books. They had orange and pale-green covers.

A dark Gujarati script, which was like Greek to me, and the symbol of an urn of fire were stamped on them. She opened one of the books to the usual portrait of Zarathustra, fat and egg-like, with his eyeballs raised to heaven. I smiled. She looked at me, puzzled, and shut the book.

‘Take all of them. Tell your mother to keep, alright? I have no use. What use have I? These things just lie and rot. Give her my blessings — wait wait — give her this sari. I’ve been wanting to send it so long - but you know how it is -’ her English broke down at this stage and she started talking in Gujarati again ~

‘No time, no servants - give it to her with my blessings}

I knew quite well what my mother would say when I got home. ‘Por thing, she knows Iwill never wear them and why does she keep sending them to me? Once, fancying the rich border of a newly sent sari, she cut it out and made it into a cap which she sold, and 2 used the rest of the sari, cut into small squares, to clean my Meceano pieces.

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com