Live

- 3 elephants electrocuted in Sambalpur

- Elevate Your Style: Handpicked Luxury Fashion & Accessories

- Ola Electric users continue to cry amid poor service, software glitches nationwide

- Panchayat Raj AE Panduranga Rao caught by ACB while taking a bribe of Rs 50,000.

- Leveraging Data and Analytics for Product Management Excellence: Mahesh Deshpande’s Approach

- Two vegetable varieties of Himachal varsity get national recognition

- Border-Gavaskar Trophy 2023-25: Bowling coach Morne Morkel says Mohammed Siraj is a legend, has a big heart and aggressive mindset

- Michael Vaughan Questions India's Decision to Skip Warm-Up Match Before Border-Gavaskar Trophy

- Rizwan Rested for Final T20I: Agha to Lead Pakistan in Hobart

- Man kills mother-in-law, injures wife and sister-in-law in J&K's Udhampur

Just In

x

Highlights

Thirty years ago, Gustavo Negrete took his wooden cross and joined other indigenous Ecuadorans to greet Pope John Paul II. But he has no interest in seeing Pope Francis on Sunday.

Thirty years ago, Gustavo Negrete took his wooden cross and joined other indigenous Ecuadorans to greet Pope John Paul II. But he has no interest in seeing Pope Francis on Sunday.

.jpg)

Like a growing number of indigenous people in Latin America, Negrete has turned his back on the Roman Catholic faith that was violently forced upon their ancestors by Spanish conquistadors.

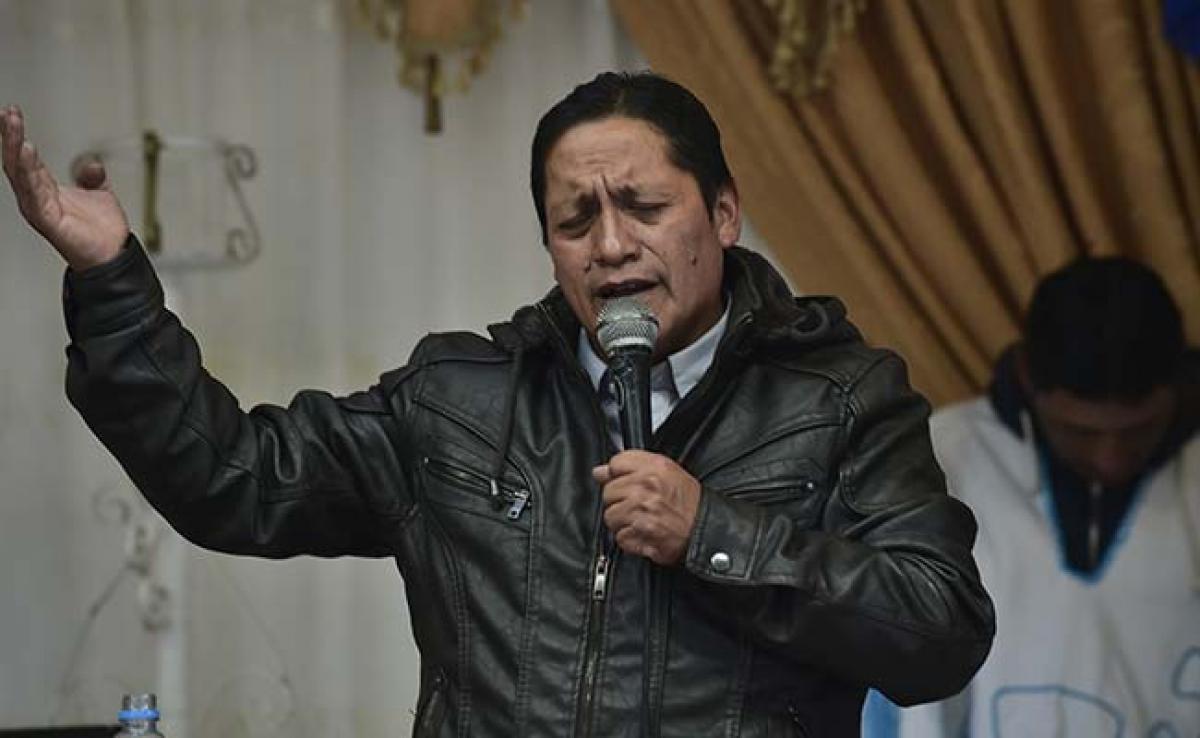

In his case, the 46-year-old Quechua became an Evangelical pastor.

Ecuador will be the first stop in the first Latin American pope's eight-day trip to the region, which will include visits to Bolivia and Paraguay.

While he vowed to bring a message of "tenderness" to historically excluded indigenous population who are victims of a "culture of waste," many have already lost faith in the Vatican.

When John Paul visited Ecuador in 1985, 94 percent of the population identified as Catholic. Today, 80 percent of the country's 16 million people are Catholic. Seven percent of Ecuadorans are indigenous people.

Negrete was 16 when he was among a group of Quechuas who welcomed the Polish pontiff three decades ago.

John Paul blessed his wooden cross, but Negrete ditched it for a protestant Bible in the early 1990s, giving up his dream of being a Catholic priest to become a pastor.

He now preaches in four temples of the Prince of Peace church.

Pope Francis "is going unnoticed today in indigenous communities," Negrete told AFP, as he held his Bible.

"The concept that we had in that era - that a representative of God was coming - no longer exists," he said.

'Estranged' from Vatican

Every Sunday, Negrete drives his car along a steep road to Llamahuasi, an Andean mountain community some 80 kilometers (50 miles) south of Quito.

On a recent Sunday, the villagers welcomed him in a modest church with music, playing guitar and keyboards as a choir of women in white dresses and purple shawls sang in Quechua.

"Christ lives!" the faithful chanted, some with tears in their eyes.

Negrete said he gave up Catholicism when he realized that the church did not punish "drunkenness, the mistreatment of sons and wives" in indigenous communities.

Memories of his father, who worked in a farm whose owners forced him to convert to Catholicism, also influenced his decision.

"To know that, while still believing in God, the Catholic church considered that we weren't people with souls, caused us to become suspicious, estranged," he said.

700 pastors vs 20 priests

Ecuador and Bolivia lack official figures on the number of indigenous people who are Protestants.

But Manuel Chugchilan, president of the Feine organization that groups indigenous Evangelicals in Ecuador, said that the number of protestant churches soared from 40 in 1980 to 2,500 today.

He said Protestants reached areas where the Roman Catholic church was absent and gained the trust of indigenous people because of the "change of life" that they offered.

Alcoholism and violence have disappeared, while families prosper because they focus on their children's education, Chugchilan said.

Another telling figure is the number of pastors and priests.

While the Ecuadoran Episcopal Conference says that only 20 of 3,000 Catholic priests are indigenous, the Feine counts 700 pastors of native origin.

Father Marco Acosta, head of the Episcopal Conference's indigenous pastoral affairs, said that "many are in the Evangelical church more out of interest than conviction."

He said he hoped that the "figure of Pope Francis, his testimony, his simplicity, his message" will resonate with the indigenous population.

Next Story

More Stories

ADVERTISEMENT

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com