Live

- AP assembly session: Govt. to introduce five bills today in house Dy. Speaker election at noon

- Reject BJP’s divisive politics in Maha: Uttam

- Travan Core Devasthanam Issues Guidelines for Ayyappa Devotees Visiting Sabari

- Independent candidate slaps election official

- SC parked Yogi’s bulldozer in garage forever: Akhilesh

- No ‘blame game’ over pollution issue: Mann

- 3 Odisha Police officers get ‘Dakshata’ award

- Punjab To Rebrand Aam Aadmi Clinics Following Central Funding Dispute

- First inscribed ‘Sati Shila’ of Odisha deciphered

- India-China Defence Ministers To Meet Following Historic LAC Disengagement Deal

Just In

It was in December 2010 that Mohammed Bouazizi, a Tunisian street vendor, self-immolated himself outside the governor\'s office in Sidi Bouzid. He died protesting against police corruption, repeated humiliation and administrative indifference.

New Delhi : It was in December 2010 that Mohammed Bouazizi, a Tunisian street vendor, self-immolated himself outside the governor's office in Sidi Bouzid. He died protesting against police corruption, repeated humiliation and administrative indifference.

This spark lit a flame in Tunisia and protests quickly spread to other parts of the Arab world, transforming into what was then known as the Arab Spring. Bouazizi's act had reflected the simmering public anger among a people that had no means to seek redress.

In Pakistan, the murder of a young aspiring fashion model, Naqeebullah Mehsud, in Karachi last January in a staged encounter, may not have led to the kind of results that the Tunisian self-immolation evoked. Yet, the sustained protests in the last three that have followed only highlight the plight and pent up anger among the Pashtun. This has forced the establishment into what looks like panic reactions.

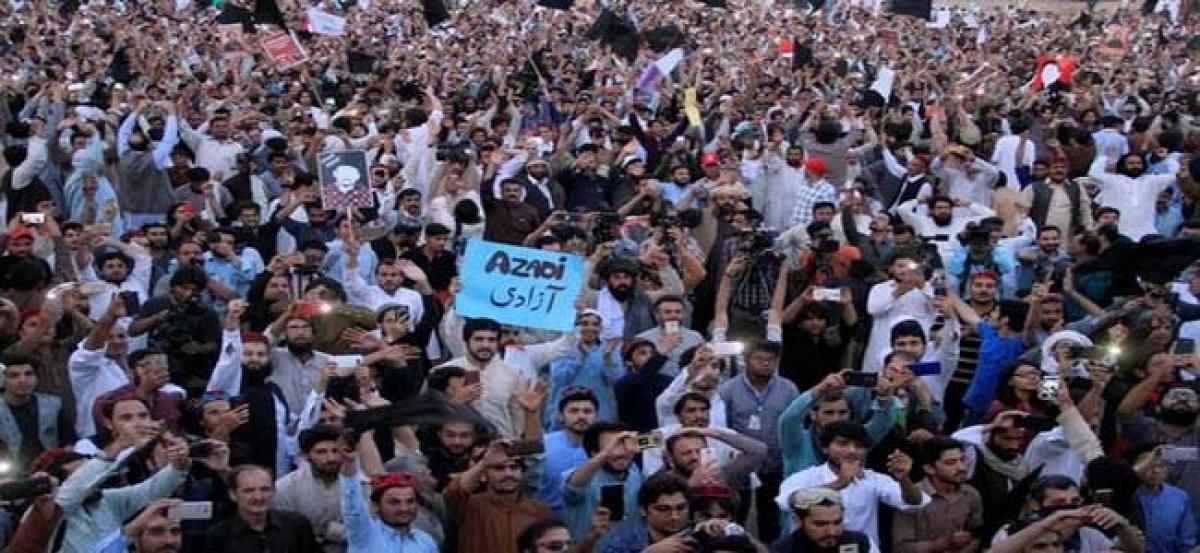

The protests have been peaceful and Pashtun men, women and even children have come from villages to have attended rallies beginning in Islamabad in January followed by other rallies in Peshawar, Lahore, Quetta, Zhob, Qilla Saifullah and parts of FATA with another one planned in Karachi on May 12.

At all these rallies, the leaders of the movement described their movement as apolitical, non-violent and seeking peaceful solutions to their problems; they insist they are not anti-Pakistan nor are they secessionists. Yet the Pashtun were bitter when PTM leader Manzoor Pashteen told the BBC that Waziristan was their(Pakistan state's) captured territory and it had taken the Pashtun 30 years to realise that they had fought the Soviets not for Islam but for American money.

The sufferings of those living in FATA have been particularly acute and most Pashtun narrate similar harrowing stories ever since the Afghan jihad. Afghan refugees had poured into FATA, Balochistan and beyond in hundreds of thousands in that decade.

The 1990s saw the Taliban largely active in Afghanistan, fighting other Afghans with Pakistani assistance. Pashtun troubles increased when the Taliban crossed over into FATA in their thousands after the American onslaught in Afghanistan beginning October 2001.

Along came Al Qaeda and their allies from among other Arabs, Chechens, Uzbeks and Uighurs as they made FATA their sanctuary. The Tehrik Taliban Pakistan was also born there and the entire lot put together made life unlivable for local Waziris, Mehsuds, Orakzais and all those other tribes who had lived in the region for centuries.

When American drones were not targeting FATA, the Pashtun had to contend with occasional Pakistan military raids and, by 2003, the Taliban were busy trying to create an Islamic emirate in FATA.

Islamabad, meanwhile, continued with action under the draconian and manifestly unfair Frontier Crimes Regulation, punishing an entire village or clan for a perceived violation by an individual. The pressure of these extremists, the continued American attacks, the excesses of the various Islamic terrorists and the Pakistan Army raids in 2007, pushed more Pashtun out from FATA to an urban centre like Karachi. FATA had become a destitute region. One of these military offensives in 2014 displaced a million Pashtun. FATA was by then suffering from full spectrum poverty with three-quarters of the population lacking all basic facilities like education, water, electricity, health. The scotched-earth tactics of the extremists, who would destroy orchards and wells, accompanied all this.

The Pashtun lived through this and now they want their rights. They want an answer to the enforced disappearances and social media depicts little children looking for their fathers. They want their area to be safe from the mines embedded there. The Pashtun leadership now asserts that this is no longer a movement for the protection of Pashtun rights alone; it is now a movement for all of Pakistan. Slogans like "Yeh jo deheshtgardi gardi isske peeche wardi hai" would have unnerved the Pakistan establishment, particularly the Army which has a 15-20 percentage Pashtun component among officers and 20-25 percent representation in the Other ranks. It naturally does not want Pashtun resentment to find expression in the army.

The reaction of the establishment has been along expected lines. First the blame was on engineered protests, implying a foreign hand. Then an attempt to portray the movement as anti-national and anti-Islamic has begun. Pashtun leaders have said they were receiving threats from Islamic extremists. Soon enough media censorship was enforced without any subtlety. The country's biggest news channel GeoTV, of the Jang Group, was the first target when its national coverage was abruptly terminated. The mainstream print media was gently coerced into submission and told not to cover the PTM's activities. Pakistan's leading daily, Dawn, had an editorial which some analysts have remarked indicated that the paper had been disciplined as it advised the PTM to negotiate with the State and advised against its May 12 rally. The PTM had suggested that the May 12 rally concerned all Pakistanis and was not an ethnic issue, thus making it a non-ethnic national democratic issue. Apparently, the Deep State has a problem with such exhibitions of solidarity.

The Pakistani media is commonly known to be free and courageous when the going is good but also known to wilt easily under pressure. Icons like Najam Sethi and Hamid Mir know what it means to cross red lines. Sethi had received a midnight knock in 1999 after he returned from a conference in New Delhi where he had made some 'indiscreet' comments, while Mir survived a bullet put through him for being too inquisitive.

Neither Daniel Pearl of the Wall Street Journal nor Saleem Shahzad of Asian Times were spared when both were seen to be getting too close to the real truth. Pearl's execution was shown on TV in 2002, while Shahzad's body was found in a ditch in 2011. Both had been terminated with extreme prejudice.

These are some of the ways in which messaging is done in Pakistan. Advisories on what to cover, how to cover and what not to cover are now frequent. Pakistan's biggest media group -- the Jang Group -- has often been in the Deep State's cross-hairs. Its billionaire owner Mir Shakilur Rehman has often been a target of state ire.

The formula is simple and effective -- Hunt for the Big Game -- the smaller beings will scurry for cover. Stories that the agitation had been started by those politicians, who did not favour a merger of FATA with Khyber PakhtunKhwa, have begun to do the rounds.

Meanwhile, Imran Khan's huge rally in Lahore on April 28 indicates that preparations for elections have begun. The PTM rally in Swat, probably bigger and more significant than the one in Lahore, went obediently unreported in the mainstream media.

The Awami Nationalist Party, the party of Khan Abdul Wali Khan, has rebuked the PTM, and is probably looking for post-election benefits.

The Supreme Court has also debarred another PML (N) stalwart, Foreign Minister Khawaja Asif from politics.

The Deep State would want all this cleaned before they announce the next stage for the election process of forming caretaker governments as a prelude to elections. This may not solve the Pashtun problem.

Mr. Vikram Sood is former Secretary Research And Analysis Wing (R &AW), Government of India.

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com