Live

- SC gives bail to SRS group head in Rs 770cr fraud case

- Hans News Service Bhadrachalam ITDA Proje

- CM Revanth Reddy to Inaugurate Women’s Empowerment Market in Madhapur

- Police Department’s Welfare Petrol Pump Inaugurated

- Polling begins for Teachers quota MLC by-rlections in East and West Godavari

- Constable’s son shines in karate championship

- MLA Nagaraju felicitates boxer Chandan

- Group-2 exam: Training programme for officials conducted

- Kadiyam thanks people for electing him as MLA

- Servotech bags 5.6 MW solar plant order from Uttarakhand

Just In

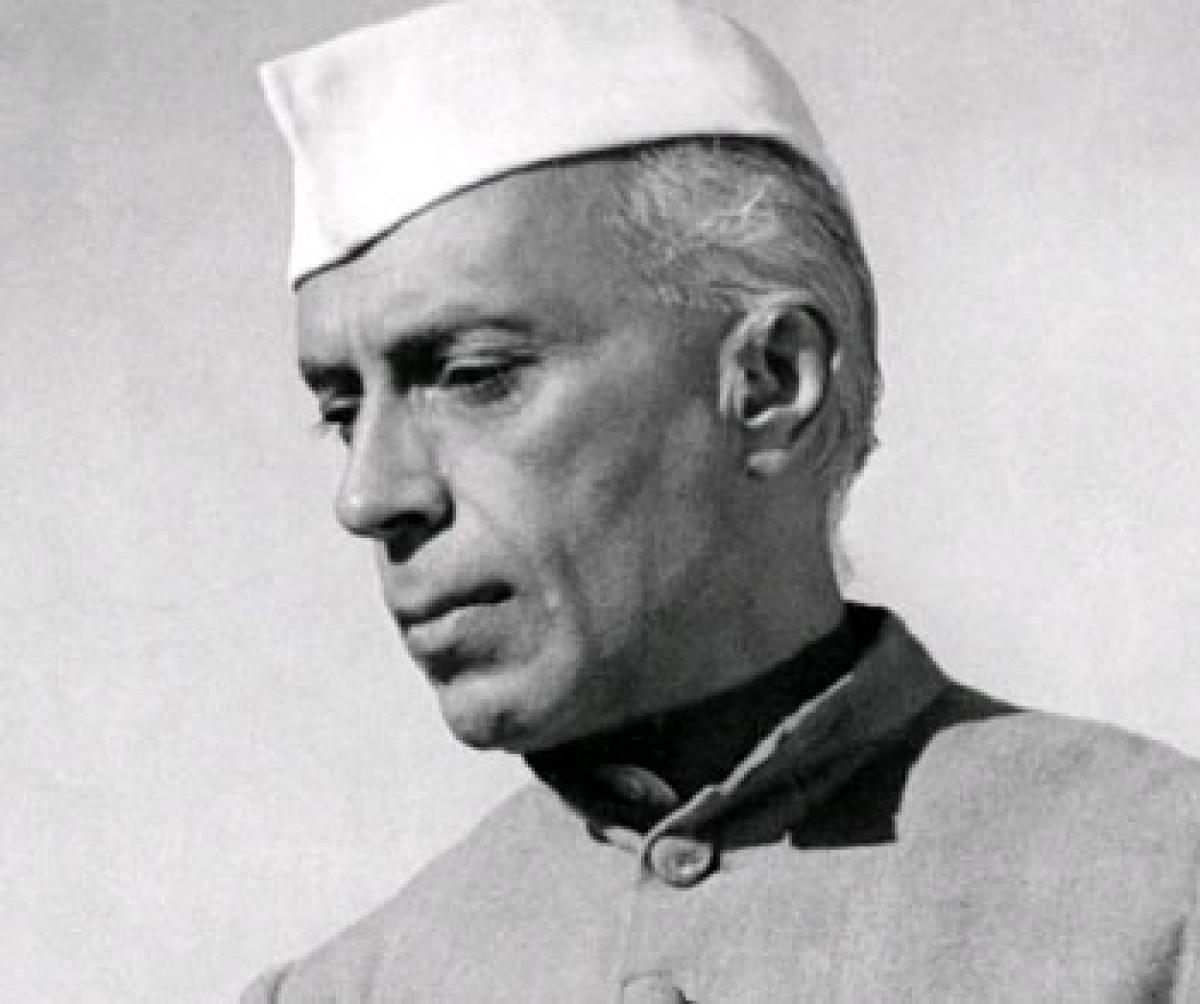

The year 2014 marked not only 125 years of Jawaharlal Nehru’s birth but also 50 years of his death. That should have been an appropriate time for a total reappraisal of Nehru.

His (Motilal Nehru’s) family mansion in Allahabad, which he acquired by his enormous legal practice, became the Congress headquarters when he gifted it away to the party. There was clearly a touch of nepotism when, by an emotional pitch of his desire to see his son as Congress President before he died, Motilal persuaded Gandhiji to anoint Jawaharlal as the Congress President in 1929 in preference to Patel who was the popular choice in the party. Patel was passed over in similar circumstances twice again in favour of Nehru (1937 and 1946).

His (Motilal Nehru’s) family mansion in Allahabad, which he acquired by his enormous legal practice, became the Congress headquarters when he gifted it away to the party. There was clearly a touch of nepotism when, by an emotional pitch of his desire to see his son as Congress President before he died, Motilal persuaded Gandhiji to anoint Jawaharlal as the Congress President in 1929 in preference to Patel who was the popular choice in the party. Patel was passed over in similar circumstances twice again in favour of Nehru (1937 and 1946).

The predominance of Nehru’s family in the governance of India and the stewardship of the Congress party, since independence has resulted in Nehruvian mystique overshadowing Nehru’s legacy. But, the lengthening “perspective of time” has brought out new facts to afford a more detached view, and enable hindsight to make a more critical evaluation devoid of passion and informed by reason.

Apart from the Mahatma, there were six dominant participants in India’s freedom struggle led by the Indian National Congress during the years 1930-1947. Three of them, viz., Jawaharlal Nehru, Abul Kalam Azad and Subhas Chandra Bose were of patrician descent. Rajagopalachari and Rajendra Prasad came from middle class backgrounds, while Vallabhbhai Patel could be truly called a plebeian.

Of all the six, Nehru had the best available education, though in terms of academic excellence, his record would not match any one of the others. Their good looks and relative youth endowed Nehru and Bose with a charisma which the others lacked. Also, both espoused and articulated radical ideas and beliefs which had a special appeal to the youth of India.

Nehru and Bose, unlike the others, were frequently at odds with Gandhiji in regard to their political thinking as also the strategy and tactics of the freedom movement. Bose was more direct and frontal in his opposition, a factor which was responsible for his forcible exit from the Congress in 1940-41. Nehru, on the other hand, would only complain of his frustrations with the Mahatma’s ‘flip flops’ but would fall in line when it came to the crunch.

The only time that he insisted on his point of view and prevailed over Gandhiji was in the period 1927-1929 when the Congress abandoned “Dominian status” for “Poorna Swaraj” as its only goal. That was also the period when Gandhiji bemoaned that Nehru was drifting away from him.

In his little known memoir “The Indian Struggle 1920-42” (the book was proscribed by the British), Bose frequently alluded to Nehru’s vacillation between his intellectual leanings towards the radical left and primordial loyalty to Gandhiji which invariably was resolved in favour of the latter. In fact, Bose declared that Nehru was chosen by Gandhiji as his successor for such loyalty. Why did Gandhiji choose Nehru as his political heir in 1942 in spite of their differences in outlook on most issues? Of all his peers, Gandhiji enjoyed the best equation with Motilal Nehru, both politically and personally.

His family mansion in Allahabad, which he acquired by his enormous legal practice, became the Congress headquarters when he gifted it away to the party. There was clearly a touch of nepotism when, by an emotional pitch of his desire to see his son as Congress President before he died, Motilal persuaded Gandhiji to anoint Jawaharlal as the Congress President in 1929 in preference to Patel who was the popular choice in the party.

Patel was passed over in similar circumstances twice again in favour of Nehru (1937 and 1946). Gandhiji was also apprehensive of Nehru leaving the Congress if he was not given the primacy among his colleagues. Not, surprisingly, it was Bose who left the Congress to plough his lonely furrow and write his own page in Indian History.

Nehru enjoyed a further advantage accruing from the ‘halo’ of sacrifice built around him by stories, some true and others fictitious, of how the family sacrificed a regal lifestyle to join the freedom struggle. In fact, the sacrifices of his colleagues could be considered greater than those of Nehru, because he gave up nothing that he had personally built up, whereas the others threw away what they had accomplished by their own sweat and toil.

For Nehru, who was at a loose end having had no taste for legal practice, it was an easy passage to politics, but it meant a painful break from the past for his colleagues. In fact, the folklore of sacrifice sat better on Motilal Nehru, the father, than on his son.

Nehru was an agnostic. However, when caught in the conflict between modernity and tradition, he leaned towards tradition. Nehru’s distaste for religious ritual and superstition was widely known and acclaimed. Yet, he performed his daughter Indira’s marriage according to Hindu ceremonial.

When his grandson, Rajiv Gandhi, was born, he wanted his younger sister to get a horoscope cast. His own will, couched in sentimental imagery of a modern human being, still yielded to traditional beliefs by suggesting that part of his ashes should be immersed in the Ganga. The same ambivalence was evident throughout his political relationship with Gandhiji.

Another major factor for Nehru’s choice was his undoubted charismatic mass appeal generated by his good looks, ‘halo’ of sacrifice and his articulation of radical ideas. The exit of Bose from the Congress left Nehru without any competition in this regard. Besides, Nehru was a compelling communicator, both in speech and on paper.

His autobiography and “Discovery of India” – not to speak of his highly popular letters to his daughter built for him a constituency even among the educated which his peers did not have. His speeches and the raw energy, he displayed during his political travels across the country, enthralled the masses.

According to Raj Mohan Gandhi, his grandfather realised by 1945 that Patel might prove to be a better administrator of free India than Nehru. Also there could have been little doubt in the light of experience since 1927 that Nehru would not have left the Congress at that critical juncture when freedom was in sight, even if Patel had been chosen to lead India into freedom. Yet, Gandhiji stuck with Nehru considering his relative youth in the hope that Nehru would follow in his footsteps once he was no longer on the scene.

As independent India’s first Prime Minister for 17 years, Nehru is credited with the following achievements: 1. A stable democracy; 2. A pluralistic and secular society; 3. A modern economy; 4. Scientific temper; and 5. A strong and modern India As Prime Minister, Nehru aimed at building a modern India free from dogma and prejudice of any kind in which individual freedom and enterprise will lead to collective prosperity and an egalitarian society.

His scorecard in this regard, is indeed, the most impressive. Moderating his socialistic and Soviet leanings, evident since 1927, he pursued a mixed economy, though with public sector at the commanding heights. His policy of non-alignment did not prevent him from persuading all the major world powers to help India build its industrial infrastructure and technological capability. He launched major irrigation and power projects to free India from the scourge of periodic famines and facilitate industrial progress.

Reflecting his scientific temper, he created a chain of National Scientific Institutions devoted both to fundamental research and technological prowess. Bhakra Nangal, Hirakud, Nagarjuna Sagar, Rourkela, Durgapur, Bhilai, Bokaro and Ranchi, Atomic Energy Commission, ISRO, ONGC, HAL, BEL, IITs and IIMs which he called the modern temples of India - all these are a living testimony to his vision and endeavors at nation-building.

As for the foundations of a stable democracy, he did attach great importance to parliamentary institutions, freedom of the Press, independence of Judiciary, constitutional rights and Rule of Law. But in his own conduct, he tended to prove right his own premonitions articulated in his famous self-critique, published in the Modern Review in 1937 under the pseudonym ‘Chanakya’. He was a copy book democrat in Parliament where the opposition was weak, though articulate and posed no threat to his position. But in the Congress party, he did not hesitate to employ any means to squeeze out dissent.

The memoirs of his colleagues in the government and the party like Azad, KM Munshi, NV Gadgil, DP Mishra and, above all, Patel’s correspondence testify to his methods. The manner in which he employed Rafi Ahmed Kidwai, a close confidante, to bring down P D Tandon, the Congress President, would offend all canons of democratic functioning. The overthrow of the Communist government in Kerala in 1959 was, indeed, a severe blot on his democratic credentials.

Nehru’s convictions about secularism and pluralism were so much beyond dispute that Patel was supposed to have remarked, in jest, that Jawahar was the only nationalist Muslim in India. But to portray him as the shield and sheet anchor of India’s secularism and pluralism would amount to ignoring Indian civilisation and ethos.

India has, right from the dawn of human civilization, a unique record of assimilation and absorption of both the invader and the immigrant. India did not witness holy wars and crusades. Of course, it had its share of communal disturbances and violence but they were due to local causes and were very much a part of the Indian experience even in Nehru’s time.

No reappraisal of Nehru is complete without a scrutiny of his foreign policy which he considered as his forte and, therefore, his exclusive preserve. His formulation of non-alignment was indeed the right prescription for India at that point of time, to enable it to tackle its internal problems of poverty, inequality and illiteracy etc., without entanglement in the cold war. But, in practice, he turned it into a third world stance of anti-imperialism.

Over time, India’s tilt towards the Soviet bloc became obvious. Non-alignment enabled Nehru to assume third world leadership, thereby enhancing his own international stature and India’s prestige. China and its leadership were yet to find their feet on the world stage which circumstance gave an altruistic Nehru the opportunity to chaperon Chou-En-Lai at Bandung and generally espouse China’s cause in the world fora. In fact, his altruism extended to the point of politely declining Russian Prime Minister, Bulganin’s offer to campaign for India’s permanent membership of the UN Security Council on the argument that it should wait till Communist China was admitted.

Ironically, what was Nehru’s favourite occupation proved his undoing. His misjudgment of the then Chinese leadership landed India into what has turned out to be an intractable border dispute. Nehru’s handling of the Kashmir issue was as ineptly altruistic as his China policy. To have taken the matter out of Patel’s hands altogether and allowed himself to be guided solely by Mountbatten was a gross error of judgment.

This was compounded by his reference of the issue to UN as a dispute between India and Pakistan and not as an act of aggression by the latter. A worse blunder was the offer to hold a plebiscite in Kashmir. The outcome of these errors is the China-Pak axis whose consequences are being suffered by India to this day.

Since Bose counted himself out of reckoning by his actions, any one of the other five lieutenants of Gandhiji could have become India’s first Prime Minister. The choice was not of the best person but the right person for the moment. Therefore, it would be futile to debate if Patel should have been the first Prime Minister. In any case, he did not live long after Independence, though he had accomplished his mission in that short time.

There can be no doubt that Nehru was a visionary with captivating charm, a refined sensibility, an acute sense of history and a national purpose. But his broad-brush vision lacked the perspicacity of Patel. His failings could be attributed to this innate deficiency. Nehru will always be venerated in India for what he had accomplished. But whenever India faces a crisis, informed Indians, even today, wish that Patel and not Nehru was alive to tackle such a crisis. That is the irony of his legacy. (The writer is former Governor of Tamil Nadu)

By P S Ramamohan Rao

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com