Live

- Indian students' concerns about employment, safety, and visas discourage them from applying to UK universities

- Candlelight Concerts Makes a Dazzling Debut in Hyderabad with Sold-Out 'Tribute to Coldplay' Show

- Shubman Gill Sustains Thumb Injury Ahead of Perth Test; Devdutt Padikkal Joins Test Squad

- Unlock Loot Boxes, Diamonds, Skins, and More Exciting Rewards with Garena Free Fire Max Redeem Codes for November 16

- Regarding the DOGE Plan, Vivek Ramaswamy stated, "Elon Musk and I Will Take a Chainsaw to Bureaucracy"

- Sudanese army says repulsed paramilitary forces attack in western Sudan, killing over 80

- Jaipur Open 2024: Baisoya makes a grand comeback to clinch title in marathon playoff against Rashid Khan

- Jamaat-e-Islami Hind President asks cadre to reach out to larger society beyond community

- Why PM mum on Caste Census, removing 50 pc quota limit: Rahul Gandhi

- Barrackpore Municipality Vice-Chairman found dead at home, suicide note suggests blackmail

Just In

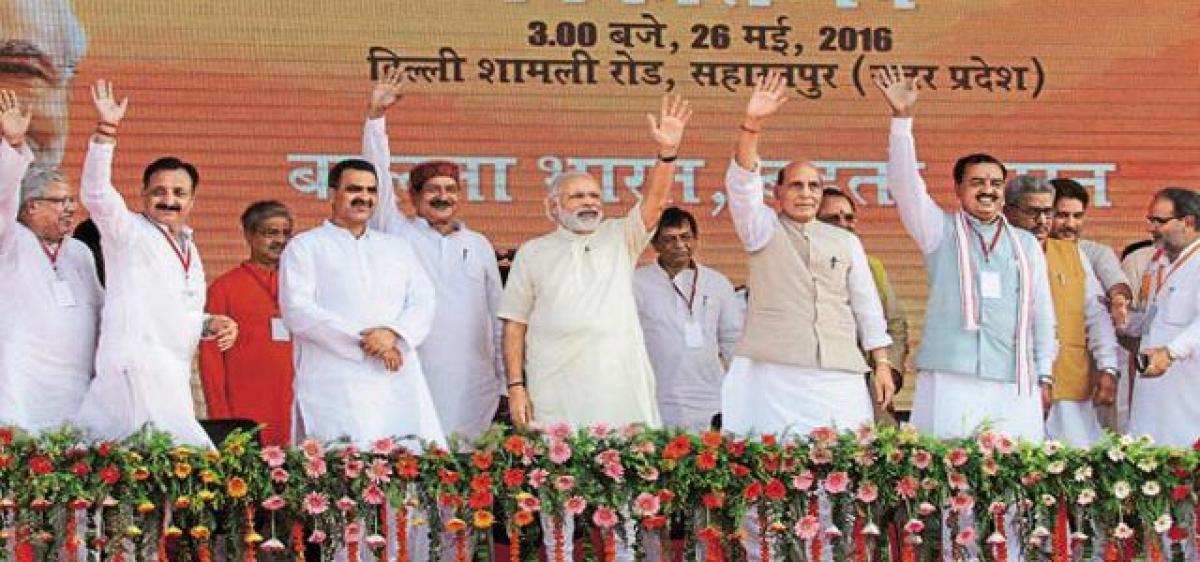

To cement his supremacy over northern and western India, Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his strategists would like to win over and secure a greater share of the significant Dalit population. Till now, though, it hasn’t been the smoothest of processes.

To cement his supremacy over northern and western India, Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his strategists would like to win over and secure a greater share of the significant Dalit population. Till now, though, it hasn’t been the smoothest of processes.

A significant Dalit section of Uttar Pradesh seem to be regular voters of Bahujan Sama Party (BSP) Mayawati, with her vote share not changing much in the past few elections.

Modi and BJP president Amit Shah are operators who are ready to do a lot to cement partnerships, as we will see, and democracy in India will take a turn for unlikely strategic tie-ups.

But the desire to include Dalits in their voter base is not new. Before the 2013 Assembly election in Chhattisgarh, the BJP flew a group of Buddhist priests around the state in an attempt to gather Dalit votes.

In May 2016, at the Simhastha Kumbha Mela in Ujjain, Shah took a dip in River Shipra, alongside Dalit sadhus. Between 2015 and 2016, Ambedkar’s bungalow in London was acquired and plans for converting it into a ‘shiksha bhoomi’ (land of education) took root.

The biggest impediment in these months was the actions of the cow-slaughter vigilantes and the incidents at Una in Gujarat. Overnight, mass Dalit mobilisations appeared, with Mayawati visiting Gujarat.

Modi defused these protests, to a certain extent, by making a personal appeal to the Dalits. It was predicted after Una that the BJP would suffer electorally.

But the BJP’s calculations withstood the events. This could be a result of the lack of regional solidarity. Or it could be that cow slaughter or its banning is not a prime electoral influence.

What has become clear is that a lot of voters do not consider either banning of cow slaughter or a belligerent assertion of religious values as primary electoral problems.

UP chief minister Yogi Adityanath’s latest move of shutting down slaughterhouses in Allahabad and other areas falls into this category. It will affect the Dalit vote in northern India as much as it affects the leather business; not enough to change electoral fortunes.

In the 2017 UP elections, the BJP successfully split the Dalit vote between the Jatav and non-Jatav communities. The BJP gave only 23 tickets to the Jatavs, Mayawati’s sub-caste, who form 57 percent of the state’s Dalit population.

On the other hand, they selected 21 candidates from the Pasi sub-caste, which is the second-largest Dalit sub-caste in UP. They also selected 36 candidates from other Dalit sub-castes like the Dhobis, the Kolis, the Balmikis, and others, who weren’t as closely associated with the BSP as the Jatavs.

Out of the 85 reserved seats, the BJP won 69, whereas in 2012 it had won 3. They put up a total of 80 Dalit candidates in 403 seats, whereas Mayawati put up 87. They also brought into the BJP, RK Choudhray and Dinanath Bhaskar, senior associates of the Dalit pioneer, Kanshi Ram.

Shah, meanwhile, attended the caste meetings of different lower castes.

Smaller communities among the MBCs like the Gaurs, the Lohars, the Kumhars, the Mallahs, and others were negotiated with. The results are for all to see. Mayawati’s vote share has declined slightly, whereas the BJP’s has shot up significantly. The others have plunged.

Caste assertion has not been the strategy of the BJP, as it once was. As a matter of fact, on the one hand, they have aggressively negotiated with caste groups, and, on the other, presented the image of a single, powerful leader. Dissociating the image of the leader from the history of the RSS has allowed them strategic manoeuvrability.

There are two ways to understand these strategies of Modi and Shah: One way of looking at this is that the BJP begins, now, to actually carry out programmes and policies for the Dalits and other lower castes in the country.

This is the narrative the current crop of Modi followers would like to believe, and there is nothing wrong with it. Except that then the BJP would have truly differentiated itself, becoming, for the first time, an upper caste party working for the empowerment of the lower castes.

That would be historic. The upper castes within the party and the Sangh may or may not support it. But if these things happen, it is doubtful they would have much choice.

The other is that Modi and Shah have, through gestures and the promise of motivational leadership, convinced sections of the Dalit community, and do not intend to devolve actual power to more than a few token seats.

Therefore, it becomes clear that the rise of Modi and the BJP is the utilisation of previously existing strategies of upper caste parties consolidating lower caste votes. (This article was first published at http://www.firstpost.com. Reprinted with their permission)

By Satyaki Roy/Pankaj Singh

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com