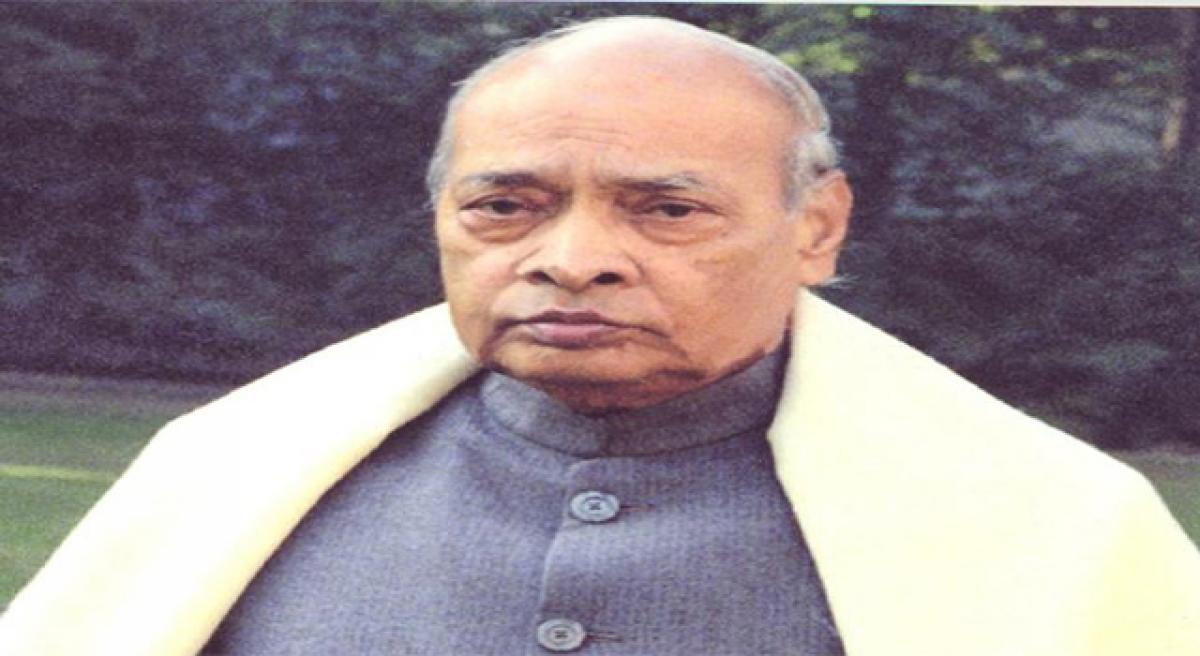

The man who re-invented India

Many thought India would become a client state of foreign powers, its economy swamped by the multinational corporations (MNCs). This did not happen. With vast arena opened up to them, Indian companies have done well. Some have themselves become MNCs.

Come Sunday, it will be 25 years of the launch of economic reforms (on July 24, 1991) by the government of late P V Narasimha Rao. With Rao’s political backing that was crucial to the process, Finance Minister Manmohan Singh gave flesh and blood to reforms and pushed them through, notwithstanding scams and confusion, distrust and fear.

Many thought India would become a client state of foreign powers, its economy swamped by the multinational corporations (MNCs). This did not happen. With vast arena opened up to them, Indian companies have done well. Some have themselves become MNCs.

Rao was not a popular mass leader. He presided over a minority government. His party colleagues did not trust him. The Gandhis of Number 10 Janpath kept an eagle eye on him. Up against great odds and with little power, he yet achieved much.

Rao had his share of human frailties and he made many costly mistakes. But his record as a reformer, transforming both the economy and foreign policy, is surely enough to place this scholar- polyglot and a ‘Chanakya’ in the Congress pantheon of heroes

Many public sector enterprises have also grown within and globally. Reforms have helped India compete and to join the global economic mainstream. Narasimha Rao wanted the reforms to have “a human face.” This was an assurance to compatriots not to panic; also to the world that India would change at its own pace.

The Indian elephant has taken time, but has walked, defying skeptics at home and abroad. Arguably, reforms have changed the way we change within and look at world. It has been slow, uneven and even misguided in some areas. Social change has not kept pace with the economic. Indeed, it has been regressive in some areas.

It has been convenient in many quarters, arguably again, to blame the reforms, their pace and direction, for many of the human resource indicators falling or not rising appreciably. The Indian pace remains elephantine. The world around, if not exactly galloping, is way ahead. China, its reforms launched 12 years before India, is a good example.

What has changed in India is that earlier, the level of backwardness was not even realised and was often justified. The new perspective entails a measure of questioning, impatience and urgency. This needs to be pushed further – into the future and not into past as some of our current social and political discourse has tended to be.

The most important thing is that the train of these reforms has chugged on. Successive governments have not sought to reverse them. This is not just to satisfy foreign investors – internal dynamism pushes them forward. Only the political fringe of different hues opposes them now.

Take one issue—the Goods and Services Tax (GST) legislation, delayed by one-upmanship, earlier of the Bharatiya Janata Party and now by the Congress since it was pushed into the opposition two years ago. Flurry of talks on the eve of the Monsoon Session of Parliament that began last Monday indicates a change in the mood. The GST may sail through in this session. Of course, one would have to await that happening before contemplating celebrations.

One is tempted to ask how Narasimha Rao would have looked at reforms and at the GST bill. He would have applauded Manmohan Singh, who nurtured reforms as the Prime Minister for ten years, for conceiving the GST legislation. Rao would have persuaded all sides concerned in and outside Parliament, long ago, to pass the GST and work pronto on its implementation.

Manmohan Singh had nurtured numerous other measures that were conceived in the early 1990s. One among them was the “Look East Policy” (LEP) that returned India to its extended eastern neighbourhood that was neglected during the Cold War era.

Rao would have applauded the Modi government for re-emphasising the LEP by changing the nomenclature to “Act East.” He would have cautioned, as was his wont, that not just slogan, it should be a course of consistent action.

Ironically, as the 25th anniversary of reforms is observed, Narasimha Rao’s role remains ignored. The Congress leadership distrusted him then and continues to do so now. On his death in December 2004, the party leadership ensured that he was not cremated in Delhi, beside other former Prime Ministers and national leaders, just as his family was adamant he should be. Eventually, Rao was cremated in Hyderabad.

Even as the Congress has all but erased Rao’s name and work from the party’s 131-year history, applause comes from the very quarters that had opposed the reforms then, but continued with them when they assumed power with Atal Bihari Vajpayee as the Prime Minister. The “stage 2” of the reforms was launched under Vajpayee’s leadership. Of course, this praise for him is because his own party has all but forsaken him.

Years after his death, Rao is being praised by some of those who worked with him. Margaret Alva, a minister under him, is readying her book “Courage and Commitment.” She said in a recent interview: “I had great respect for him, although I, like the others, was greatly upset with him on the way he had handled the Babri Masjid and some other issues.

But the point is, whatever may have been wrong, he was a Prime Minister, a Chief Minister, a Congressman; he made his contribution. In death, one needs to respect the individual, whatever your differences, and I did feel strongly that he had been wronged.”

Jairam Ramesh is another Congress leader who had closely watched the reforms process. In his book published last year on the first 100 days of the Narasimha Rao Government, Ramesh, risking the wrath of the party leadership, argues that Rao’s role in the 1991 reforms blitz was defining.

He recalls how Rao neutralised criticism to the radical economic reforms both from sections of the opposition – from the ‘nationalist’ or rather conservative Right and the anti-American Left – and from within the Congress.

That was also the moment when India had felt ‘abandoned’ in the international arena by the sudden demise of the Soviet Union, the biggest ally, and the total collapse of the world order that had shaped during the Cold War era. Rao steered India through bad times.

As a result of the reforms, investment from overseas, both foreign direct investment and capital from abroad in search of assets – shot up to $5.3 billion in 1995-96 from $132 million in 1991-92. But the reforms, from a double devaluation of the rupee to de-licencing of industries and much else, proved to be the easier part. Breaking from the Nehruvian economic paradigm and the fight for support within the Congress were to prove significantly tougher.

Like it had happened with the late Indira Gandhi, several satraps like Arjun Singh and N D Tiwari supported Rao thinking that he would be a stop-gap for their own political plans. But Rao dug in. The latest effort is by Princeton University scholar Vinay Sitapati. His book – Half-Lion: How P.V. Narasimha Rao Transformed India – draws on Rao’s voluminous personal records to rethread, posthumously.

His largely sympathetic portrayal draws Narasimha Rao as the first person outside the Nehru-Gandhi family to have completed five years as Prime Minister. This was despite his lacking in charisma (“charisma of a dead fish,” as Ramesh puts it) like the Nehru-Gandhis.

Rao was not a popular mass leader. He presided over a minority government. His party colleagues did not trust him. The Gandhis of Number 10 Janpath kept an eagle eye on him. Up against great odds and with little power, he yet achieved much. Rao had his share of human frailties and he made many costly mistakes.

But his record as a reformer, transforming both the economy and foreign policy, is surely enough to place this scholar- polyglot and a ‘Chanakya’ in the Congress pantheon of heroes. In 2014, political writer Kapil Kommireddi held that “if Jawaharlal Nehru ‘discovered’ India, it can reasonably be said that PV Narasimha Rao

reinvented it.”

Among Rao’s last words was expression of a hope that his contribution to the nation would be better appreciated after his death. Perhaps, that time has come. Or has it? The authors cited above are all from the South. Delhi still ignores him.