Live

- They always want me to win, and now I feel lucky to have been offered a story like ‘Zebra’: Satyadev Kancharana

- ‘Democracy first, humanity first’: PM Modi in Guyana's parliament on two countries' similarities

- PKL Season 11: Telugu Titans register third straight win to top standings

- Is Pollution Contributing to Your COPD?

- NASA Unveils Underwater Robots for Exploring Jupiter's Moons

- Additional Central forces arrive in violence-hit Manipur

- AR Rahman and Saira Banu’s Divorce: Legal Insights into Common Issues in Bollywood Marriages

- 82.7 pc work completed in HPCL Rajasthan Refinery area: official

- Curfew relaxation extended in 5 Manipur districts on Friday

- Tab scam prompts Bengal govt to adopt caution over fund disbursement

Just In

Let it be stated at the outset that it would be naïve, foolhardy and against India’s national interests if it was not carrying out espionage in a neighbouring country, especially in a perennially hostile Pakistan. Chanakyaniti prescribes it as a necessity. A state must carry out its saam, daam, dand and bhed for its safety and well-being.

For one, Jadhav is a civilian who was doing legitimate business on the Chabahar project in Iran, and this is corroborated by Iranian authorities. The project has India, Iran and Afghanistan as collaborators. It is essentially meant to bypass Pakistani territory. Islamabad has no reason to like it. Indeed, it even jeopardised its ties with Iran by announcing Jadhav’s catch last year, and alleging that he was “operating from Iran.”

Let it be stated at the outset that it would be naïve, foolhardy and against India’s national interests if it was not carrying out espionage in a neighbouring country, especially in a perennially hostile Pakistan. Chanakyaniti prescribes it as a necessity. A state must carry out its saam, daam, dand and bhed for its safety and well-being.

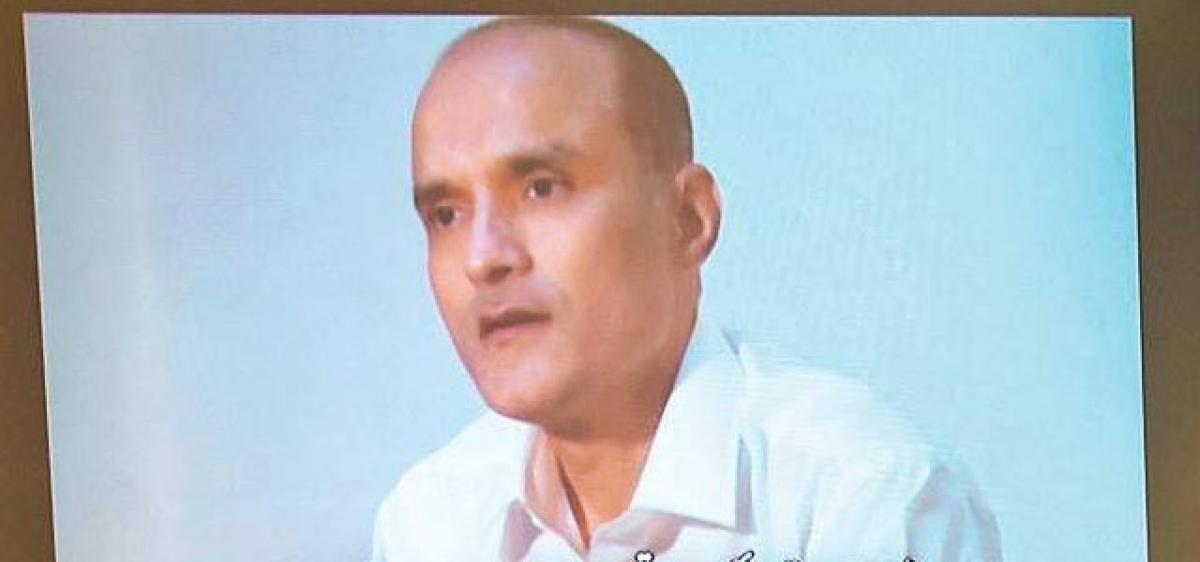

Spying has been commonplace in statecraft from times immemorial and India has been both its practitioner and target. It has never been – can never be – one-sided. The cat and mouse game, as they say in modern times, goes on. So, let us attempt a balanced picture when we react and respond to the latest round of acrimony over the death sentence handed to Kulbhushan Jadhav by Field General Court Martial, a military court in Pakistan.

That said, this is not an acknowledgement that Jadhav was or is an Indian spy, an operative working for the Research and Analysis Wing of the Union Cabinet Secretariat. Nor is this an approval of the way Pakistan has handled the issue.

The perennially uneasy neighbours are in for a prolonged impasse in their already strained ties because India will do its best to save Jadhav from what it has called “pre-meditated murder” and Pakistan is unlikely to give up this prized catch that avenges its many grievances including Ajmal Kasab’s hanging by India after the Mumbai terror attacks.

At the same time, both sides have been quick to let some of the steam off by releasing detenus – two by India and some 66 by Pakistan. For a change, the innocents are not held hostage to the current crisis. But Pakistan High Commissioner Abdul Basit, who missed being made the Foreign Secretary, has sought to queer the pitch with his remarks hoping, as he is being replaced soon, to receive a hero’s home-coming.

Basit reflects Pakistan’s “hey-we-caught-you” mood as Pakistan Defence Minister Khawaja Aseef connects Jadhav with the 2002 sectarian killings in Gujarat and Samjhota Express and much else. But Islamabad needs to answer many questions that India and the world community are bound to raise.

For one, Jadhav is a civilian who was doing legitimate business on the Chabahar project in Iran, and this is corroborated by Iranian authorities. The project has India, Iran and Afghanistan as collaborators. It is essentially meant to bypass Pakistani territory. Islamabad has no reason to like it. Indeed, it even jeopardised its ties with Iran by announcing Jadhav’s catch last year, and alleging that he was “operating from Iran.” This was even as Iranian President Hassan Rouhani was on a state visit. This acrimony has slowed down the Chabahar port project.

Next, a former Indian Navy commando, Jadhav, was kidnapped by the Afghan Taliban using Pakistani territory to attack Kabul. Indeed, one of their ‘shoora’ (assembly) exists and bears the name of Quetta Shoora that Pakistan Army’s Inter Services Intelligence (ISI) controls.

Jadhav was sold to the ISI. Then German ambassador in Islamabad, Guenter Mulack, went on record on this. Why, even Sartaj Aziz, who is de facto Foreign Minister had said last December that no conclusive evidence had been found against Jadhav. Is this, then, a case of military over-ruling the civilians?

Pakistan resorted to trying Jadhav, an unarmed civilian and a foreigner, in its military court, tactically fortifying itself from challenge before any civilian court. Strategy analyst and former Indian diplomat M K Bhadrakumar, who had dealt with Pakistan when at the foreign ministry, has said that the military court route used for Jadhav’s trial precluded intervention by the Supreme Court.

However, talking tough and calling Jadhav “not just son of his parents,” External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj has assured that best lawyers would be provided to Jadhav to appeal at the apex court. The only other route left for Jadhav is to appeal for mercy to Pakistan President Maumoon Husain, who is but a titular head with no say in the governance, least of all in what the military establishment would want.

Any mercy petition will likely be kept pending, like it had happened in the case of Sarabjeet who was eventually killed by jail inmates. Jadhav’s jail-stay could also be tricky and risky.

Acknowledging that Jadhav is an Indian national at the outset – Pakistan took five months to acknowledge Kasab’s nationality – India sought consular access 13 rimes. Pakistan now says it rejected them because Jadhav was engaged in “subversive activities.” But so was Pakistani Mohammed Ashraf Mahmood, convicted for taking photographs of defence installations, convicted and jailed in Hyderabad, awaiting remission of his 14-year jail term.

The differing standards are obvious. The alacrity with which the Jadhav case has been ‘resolved’ in a year’s time ought to have been shown in the case of Mumbai terror attacks. The military courts’ credibility is a hush-hush matter in Pakistan out of fear of anything military. Sections of its media put the verdicts handed down by these courts with disclaimers, like putting “hardcore terrorists” within quotes. Military courts, extended last month after much acrimony in parliament, are accepted, instead of judicial reforms, as they are seen as more efficient than civilian courts and respect and awe for anything in uniform.

The military courts handed down death sentences to as many as 87 people in 2015 and varied punishment to many others. Some were convicted for conspiring to kill then military dictator Pervez Musharraf or aiding terror attacks on military establishments. But the bulk of them were murder convicts. There is virtual rejoicing that the 2016 figure of hangings reduced by 73 per cent, even though Pakistan is among the top five nations hanging its citizens.

Jadhav’s death sentence came immediately after a retired Pakistan Army Lt Col Mohammed Zahir went missing from Lumbini in Nepal, close to the Indian border, where he had gone in response to a mysterious job appointment. Is there a connection and is this likely to be a bargaining chip by the two governments?

Only last week, the United States indicated its keenness to get India and Pakistan to talk and resolve issues “before things happen.” But after India’s rebuff, Washington returned to its earlier stand that the disputes are bilateral.

Nevertheless, the American National Security Advisor, retired General H R MacMaster, will be in New Delhi shortly to talk to his counterpart, Ajit Doval. Although the subject is said to be Afghanistan-Pakistan situation, the worsening Indo-Pak ties are bound to be discussed in the light of the Jadhav affair.

The Trump administration has not been happy at the way Pakistan is sheltering select terror groups to use them against India and more importantly, against 9,000-plus American troops stationed in Afghanistan and the Ashraf Ghani regime in Kabul.

Reports say that the previous Obama administration repeatedly did, Trump’s Defence Secretary Jim Mattis may refuse to certify release to Pakistan of $350 million out of the $900 million Coalition Support Fund. But neither the US, nor the world community, will abandon Pakistan that holds the gun to its head in the form of nurturing and export of terror groups.

Such is the India-Pakistan relationship that the Jadhav sentence has united the political class in both India and Pakistan. But there is a difference. Jadhav’s sentence by a military court has been approved by Pakistan Army Chief, General Bajwa. The Indian military has let the government and parliament do the talking, which is as it should be.

The ground reality of this complex relationship lies somewhere between the well-meaning candle light-burning vigilantism and impotent jingoism caused by blind hatred for anything Indian and Hindu or anything Pakistani and Muslim.

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com