Live

- Delhi Mayor poll: Cross-voting shows AAP councillors’ frustration, says Congress leader Jitender Kochar

- NIA files fresh charges against Mizoram-based arms trafficker

- From appeasement to 'New India' pitch: Nadda credits PM Modi for changing style of politics

- Bihar liquor ban gave rise to unauthorised trade, means ‘big money’ for officials: Patna HC

- COP29 Presidency launches initiative to address climate change, humanitarian needs

- Bangladesh's October foreign reserves fall below 20 billion USD

- CM Vijayan's top aide Sasi takes legal route in fight with MLA Anvar

- Dhirendra Shastri supports Yogi Adityanath's 'batenge to katenge' slogan

- Top 10 Most-Watched OTT Releases of the Week (Nov 4-10)

- Istanbul nabs over 240 illegal migrants

Just In

Should modern-day cricket need to put in restrictions on bat sizes?

Cricket has been one of the prolific games in the world and the game has evolved over the years with new rules or formats coming into the fore.

Cricket has been one of the prolific games in the world and the game has evolved over the years with new rules or formats coming into the fore.

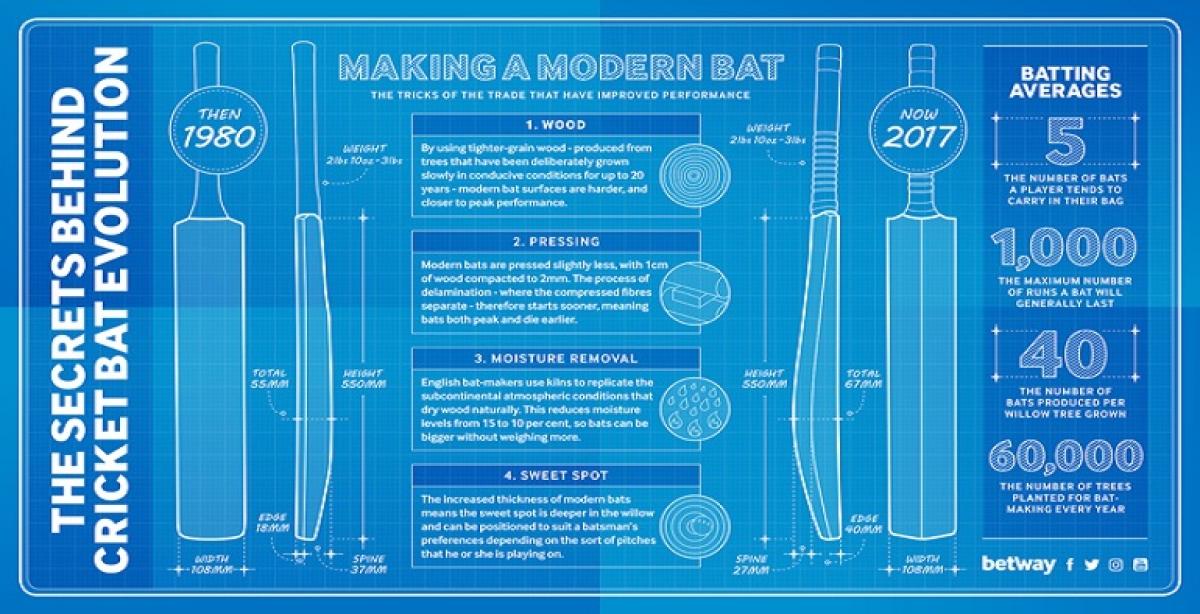

Particularly, for the batsmen, the changes have turned beneficial - be it the shorter boundaries or the thicker bats. With cricket balls crossing boundaries more than ever before, the bats have become the main weapon to post more runs.

In the previously held World Cup in 2015, the number of deliveries hit for boundaries have doubled when compared to the one-day internationals held in 1980.

Earlier, setting up a target of 300 was a huge task for the batsman, but the batsmen are hitting all over the field scoring a total more than 400 runs, which has so far been achieved 18 times.

However, with the constant run chasing and focus on higher targets, the game is slightly inclining towards the batsman's side.

Bringing about a change, the MCC World Cricket Committee has given their nod to limit the size of the bats and it will be put into effect from October 1, this year. Whether it would be harder for the batsmen to score boundaries is not yet certain.

Dwelving a little bit deeper, the reality of a modern-day cricket bat has not changed to a large extent with the bat weighing nothing more than it has done in the past.

Providing more insight in this regard, Chris King, a personal bat-maker who works for Gray-Nicolls, a manufacturer in the business since the 19th century, told the Betway Insider: “Everybody gets obsessed with the shape of the cricket bat, but the actual power comes from how well the piece of wood is pressed."

He further says, "But that is an area of bat-making that most people don't understand. They assume it's just the size. If it was that easy, it would be a lot easier to make a good cricket bat."

King, who provides bats for England's Alastair Cook and Alex Hales, Australia’s David Warner, New Zealand’s Kane Williamson and South Africa’s JP Duminy also said, "I often joke with people on social media that it’s like saying a Ferrari is fast because it's red. It completely undermines what the engine is.”

Coming to the making of the bats, batsmen now use modern bat surfaces that are harder with tighter-grain wood obtained from trees grown slowly conducive conditions for up to 20 years.

This delivers peak performances but durability factor decreases, however, it doesn't leave it's impact on the size or the weight of the bat.

Former England captain Nasser Hussain and current England wicketkeeper Jonny Bairstow recently conducted an experiment bringing to light the other factors behind the hard-hitting game for the batsmen.

In the experiment, both used the same bat and attempted to hit six balls into the stands continuously. While Bairstow managed to do so five times, Hussain was unable to clear the boundary rope once.

Chris King who made both the bats said, “Nasser was using Bairstow’s second bat from the same pair, so I know they were the same."

“Nasser asked, ‘Why can’t I do it?’, and Jonny replied, ‘Because you’re hitting it wrong, your position is wrong, and you need to get in the gym!’

“There is a lot of belief that it must be the big bats, whereas actually it is a lot more to do with the professionalism of the sport. They play different shots now.”

Elaborating further, the batmaker said, "It tends to be driven by the top end of the game. All it takes is somebody like David Warner to be constantly getting it over the boundary while using a very obviously large cricket bat and everybody sees it as a shortcut to being successful."

“That is also supported by commentators, because they are ex-cricketers from the ‘70s and ‘80s, who see these guys hitting boundaries all the time, hitting massive sixes, and the first thing you see is the fact that their bat is different to what you used to have.”

Pressing technique – whereby the fibres of the wood are compressed together to firm up the blade in preparation for hitting a hard ball – has not changed much down the years, though bats are pressed slightly less nowadays."

The inception of it King suggests to some point in the ‘90s, "India and Pakistan started producing large quantities of very high-quality cricket bats at a very low price, so the market suddenly got filled with these high-quality bats that were more and more dramatic."

“They fit with that Bollywood approach to cricket – the IPL and that sort of feel. Nobody has ever gone back.”

With so much complicated manufacturing involved, it's easy to assume batsmen too brood over the bat selection and maintenance.

King, however, says that batsmen’s personalities vary. Citing West Indies batsman Shiv Chanderpaul and England’s Marcus Trescothick as fussy operators, he said, “Hales has got a particular shape, size and weight, but once he has it delivered, he basically just takes them out and plays with them.”

“Chanderpaul came in because the West Indies were touring England. He’s very discerning about his willow. So when he found a nice one in the workshop, he asked for it to be made into a cricket bat.

“He got about 80 in the first innings and 90 in the second, and from then on I made every bat that he used until recently.

“He has a whole process of preparing the bat. He knocks it in, he plays with it, he practises with it. He’ll add a bit of tape, I think he even seals the top of the shoulders with a kind of glue to stop moisture getting in.

“In general, though, you find that if you make a bat for somebody and they do well, you’ll be making that bat again because they think the way it looks means it will have the same performance.

“If only it was that easy.”

The batmaker reveals that the restrictions brought in to fluctuate the balance of modern cricket will encounter no change.

“Bat-makers all find it quite funny because literally they are going to have no change whatsoever.

“To be honest, the dimensions that they have given us aren’t that terrifying anyway,” he says. “It’s not like they’re going back 20 years.”

Rule changes aside, he doubts how much further bats can really evolve anyway.

Not that that will stop him, and others in his profession, from eking out every advantage possible.

“I often say that as manufacturers we’re a bit like Formula 1 now, in that we take the materials and push them to their absolute limit.

“It’s like anything nowadays. Most people’s family car is probably more powerful and more finely-tuned than a sports car was 15 years ago. It’s the way everything progresses.

“Can we go any further with it? I don’t think we can because we’re restricted to certain materials and by the laws of cricket. I guess it’s the bowler’s turn," he concludes.

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com