Live

- Gambhir is prickly character: Ponting

- Gurpreet backs Manolo, says Asian Cup qualification imp

- Pak should stop playing cricket with India: Latif

- Tilak’s brilliant ton helps India beat SA

- Vedanta Aluminium observes Global Handwashing Day

- Found ‘formula’ to get rid of Smith: Ashwin

- Onion price rises to Rs. 70 per kg

- Indian batters can’t stand up to Oz pacers: Haddin

- Odisha govt to return land acquired for Vedanta University to owners

- Trump Cabinet 2.0: Complete List of Key Appointments, Featuring Musk, Ramaswamy, and Ratcliffe

Just In

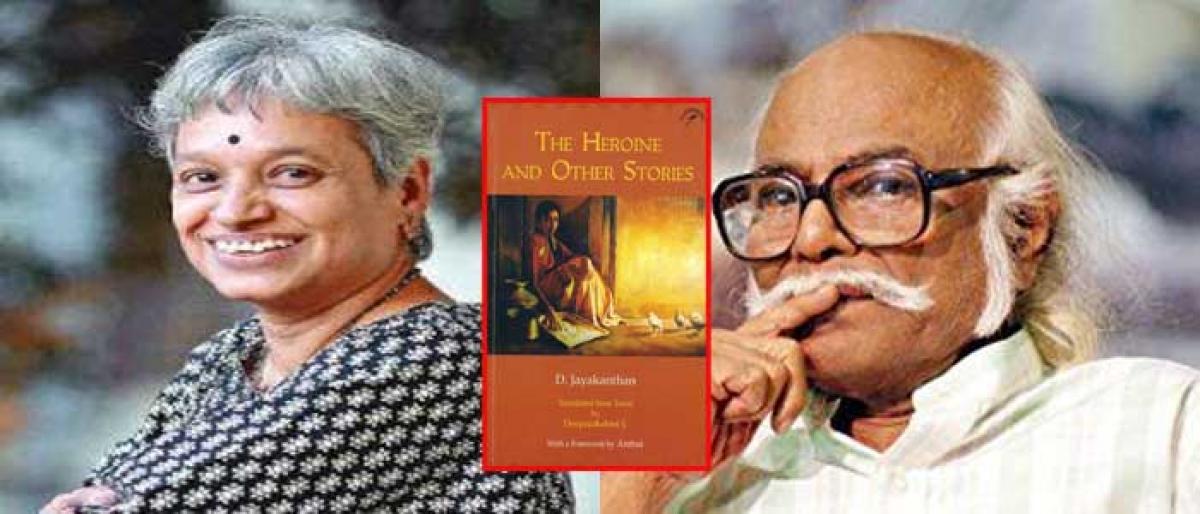

My generation grew up with some very fine writers but we always felt that Jayakanthan was one of us and that he spoke for us. He was JK to us. We romanticized his unconventional life and writing. We loved him and also hated him at times, for we did not want him to have any of the failings of an ordinary writer. He never asked us to put him up on a pedestal but we did and then occasionally when he

My generation grew up with some very fine writers but we always felt that Jayakanthan was one of us and that he spoke for us. He was JK to us. We romanticized his unconventional life and writing. We loved him and also hated him at times, for we did not want him to have any of the failings of an ordinary writer. He never asked us to put him up on a pedestal but we did and then occasionally when he fell down, we felt he had betrayed us.

We felt that we could criticize him, as much as we admired him, for his stories—with people we saw in everyday life- made us feel that he was as simple or as complicated as those characters we felt close to. I don’t know about others, but as someone who grew up in Bengaluru away from Tamil Nadu, for me JK was the rebel I dreamed of becoming. And that is how I imagined him till I had two encounters with him.

In 1964 I came to Madras Christian College (MCC) to do my MA. The college’s Tamil Department, at one point, organized a debate on the topic of whether there should be co-education or not. JK was invited as the chief guest. I was not a participant but when one boy after the other went up on the stage and began to talk of girls as detractors, enticers and seducers, commenting on the way girls dress and behave, I lost my cool, took permission to say a few words and blasted the boys who spoke of girls in this manner. When it was his turn to give the address, JK said that such fights on the stage seemed very uncultured and that debates must be done with finesse.

On the return that evening, when I got into the electric train from Tambaram, JK was in the same compartment. I could have spoken to him and he would have probably not minded chatting. But I was too angry with him for calling me uncultured. Within a few months JK was giving a talk in George Town and since I happened to be there I attended it.

He got into a big argument with a person, probably from the DMK, who used rather uncouth language and began to shout, ridiculing the actor MGR, saying he wore a wig, and used some abusive language.

I came back to the hostel and had the impudence and temerity to write and ask him if he was a schizophrenic for he had said in the college it was uncultured to fight on the stage and he had done something worse than that-he had used abusive language. Of course, I got no reply. But on another occasion a few months later when I attended another talk of his, I was sitting right at the back and was the only woman in the audience.

After the event, when I was walking away JK called out to me. ‘Aren’t you the one who wrote me that letter?’ he asked. ‘Yes, but you didn’t reply,’ I said. ‘I am not schizophrenic; it is just that sometimes we get emotional and get overwhelmed,’ he said and smiled. It was a kind of apology.

Many years later when he had been invited to speak at the Jawaharlal Nehru University, he saw me in the audience and came up to me and asked, ‘Aren’t you the same MCC girl?’ I was quite amazed at his memory. But in the intervening years he had written a lot that had both angered and won my admiration. I had a chip on my shoulder about at least one story and the sequels he had written.

In November 1966, when his ‘Agni Pravesam’(The Fire Test) was published, I had just turned 22. The story was considered a very bold one, for it is about a young college student coming back home on a rainy day, taking a lift from a rich man with a posh car and getting seduced by him. She comes back home and narrates the whole incident to her mother, who initially reacts with anger but later gives her an oil bath and tells her that the water poured on her had purified her.

A group of us thought that the story fell short of being really radical if the girl had to be even metaphorically purified. What had she done wrong? And where was the need for this mock fire test recalling the fire test Sita was subjected to? And why was the story named Agni Pravesam emphasizing that the girl had undergone a metaphorical version of fire test? We were furious.

But the stories that came as responses to this ‘bold’ story, with terrible punishments meted out to the girl with her actually burning in fire, told us that, maybe, the time had not come for even JK to write that a girl can get furious about seduction but need not be destroyed by it. Not that we were willing forgive him for the sequels, and the film that followed sometime later made us even more furious, for JK was striving to prove that Ganga, the heroine, was pure.

The JK one could engage with, maybe, had changed over the years, for during his stay in JNU there were hardly any debates with him. Not even about some of the wonderful stories of his that we liked, such as ‘Kokila Enna Seythuvittual’? (What Had Kokila Done?), ‘Karunuiyinul Alla’ (Not out of Sympathy) and the novels ‘Oru Munithun’, ‘Oru Veedu’, ‘Oru lllagam’; ‘Parisukku P0’ and many other stories, some of which had been written at the time when we idolized him and which are included in this collection. He was already an icon who had won the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1972, at the age of 38, and who had said that the Akademi had honoured itself by awarding him! Jayakanthan lived to write many controversial stories, never failing to inspire many generations of youngsters and fans who always were around him. There were stories about the ‘darbar’ he held on the terrace of his house, but he was always surrounded by men.

I often wonder which stories of his I would choose, if I were asked to put together a collection of his work. Some of the stories I definitely would have chosen are not in this collection but then this is a collection put together by his daughter, who not only saw him differently as a person, but also saw his stories differently. She is the daughter who sang for him even when she was leaving the house in a hurry and he told her to sing Bharati’s ‘Ninnui Charunaduinthaen Kannammu’ (I have taken refuge in you). There is a beautiful photograph of Jayakanthan standing bare-bodied in a lungi and little Deepalakshmi looking up at him and he looking tenderly at her.

I think that closeness must have made her choose the stories in this collection differently from how I would have. These stories are about complexities in a vast spectrum of relationships; about defiance and succumbing and about human frailties and strength. There are some extraordinary women and men in these stories —women who are not afraid to throw a man out of the house when betrayed, women who stand by one another against an autocratic man in the family and reduce him to pulp, women who can wail for the dead child of another, men who can cry unashamedly and also men who can define friendships. These are stories that present the range of JK’s writing from a very different perspective.

These are stories which Deepalakshmi’s discerning eye and her heart that understood JK for what he was, have chosen for their nuances and subtleties and for themes that can never fade away over time.

Very competently translated, not straying away from the original, and yet not getting caught in just the words of the original, the stories come alive as much as the original Tamil ones, which belonged to a different period but are relevant for all times. I can only say that had JK been alive, he would have probably asked Deepalakshmi to come close to him, caressed her head and told her to sing for him, “Ninnui Charunadainthaen Kannamma” in her evocative voice. And Deepalakshmi would have obliged her father.

Extracted with permission.

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com