Live

- Kiran Abbavaram's Hard Work Pays Off: Bunny Vasu Lauds Ka Team at Success Meet

- PM Modi’s welfare schemes transform rural lives in Bokaro, residents share gratitude

- We will ensure Bangladeshi infiltrators are removed from Jharkhand: BJP's Gourav Vallabh

- Hezbollah fires five rockets at central, northern Israel: sources

- HM Amit Shah, Rajnath Singh to address several rallies in Jharkhand tomorrow

- Will not waste single day in getting back what we lost, Omar Abdullah tells Assembly

- PM Modi visits Advani's residence to wish him on birthday, shares special moment

- Sun-Dried Cotton to Be Taken to CCI Purchase Centers, Avoid Middlemen - Collector

- Survey Process Requires Public Cooperation - Collector Badavath Santosh

- Distribution of Maize Seeds to Farmers at Agricultural Research Center

Just In

Clumps of dull green weed float in a bed of water. This is no river I am looking at, but one of the food trays on the buffet table. It is breakfast time at the Bhutan Mandala Resort, Paro.

Clumps of dull green weed float in a bed of water. This is no river I am looking at, but one of the food trays on the buffet table. It is breakfast time at the Bhutan Mandala Resort, Paro.

‘What is this green stuff?’ I ask the lone waitress.

‘Churu jaju,’ she says brightly.

‘And what’s churu jaju?’

I can almost hear her mind whirring.

‘It is... it is... (light of brilliance in her eyes) seaweed!’

The only other steel tray has fried rice. Looks cheesy. There are some bananas on a dinner plate.

‘Do you have anything else for breakfast today?’

The smile fades from her face. ‘No....’

‘Simple things, something you don’t have to cook? Bread, butter?’

By this time, another waitress has joined her from the kitchen.

‘Y-yes, bread, butter possible.’

I push our luck: ‘Maybe two omelettes?’

‘Y-yes. Please wait at table. We get.’

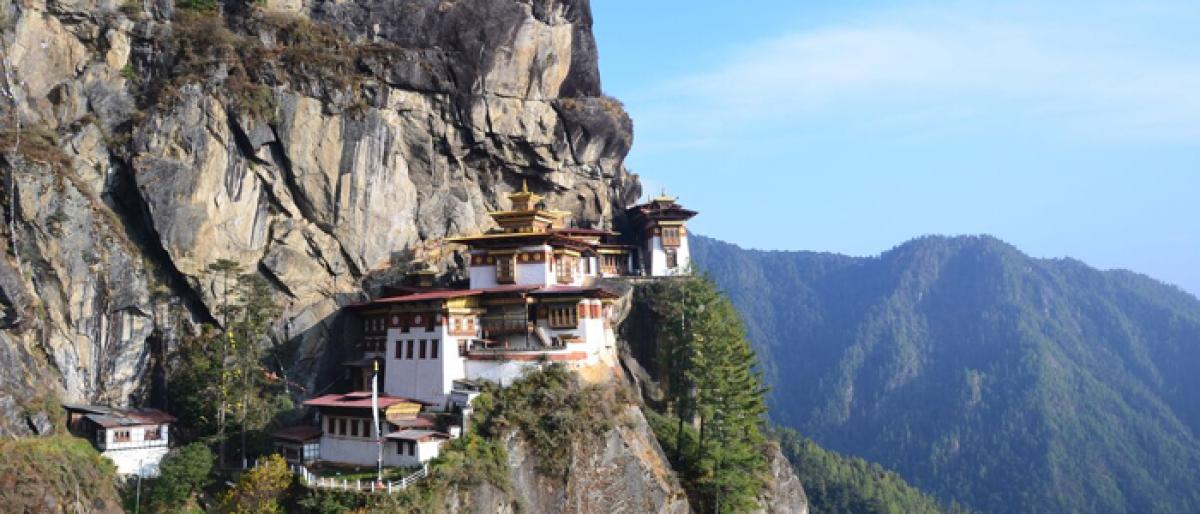

Today, our penultimate day in Paro, we will trek 3,000 feet uphill to Taktsang Palphug Monastery, or the Tiger’s Nest, 10 kilometres north of the town.

Legend goes that the fiery Dorje Drolo, one of the eight manifestations of Guru Rinpoche, flew to a cave high up on a mountain on the back of a tigress. The flying tigress was a form assumed by Yeshe Tsogyal, the Guru’s consort.

A flying tigress. I am reminded of this conversation between Tigger and Roo in The House at Pooh Corner:

‘And as they went, Tigger told Roo (who wanted to know) all about the things that Tiggers could do.

‘ “Can they fly?” asked Roo.

‘ “Yes,” said Tigger, “they’re very good flyers, Tiggers are. Stornry good flyers.” ‘

Guru Rinpoche meditated in the cave for three years, three months, three weeks, three days and three hours to subdue eight types of evil spirits. He then converted the Bhutanese to Buddhism.

In 1692, Paro penlop Gyalse Tenzin Rabgye built the first monastery around the holy cave. It is said that when the monastery was first built, it was anchored to the cliff by the hairs of khandromas, female celestial beings. A severe fire devastated the lhakhang in 1998, and it had to be reconstructed.

Tandin drives us to the base of the Taktsang mountain range. He takes a photo of Sumita, Ugyen and me. In the photo, the Tiger’s Nest is but a white speck high up on the towering mountain.

Tandin wishes us luck. He is going to stay behind with the car, wait for our return.

This is the starting point of the trek: horses and mules waiting to be hired swish their tails and flick their ears at flies under a row of tall pines; women set up little benches covered with red cloth and bring out ethnic jewellery from sacks; an old man sells trekking poles made of white, unpolished oak.

‘I could do with a pole,’ says Sumita. Ugyen buys her one, for Nu 50.

Ten minutes into the gradient, I am short of breath. That is normal: even a short flight of stairs at sea level makes me breathless, always has since childhood.

Sumita is slowing down, too. That is quite unusual. Ugyen is unsympathetic. ‘You should not start halting already; we have a long way to go. Walk slower if you wish, but keep walking.’

Each step on the trek is a foot high, made of a long log placed on a row of stone slabs broken from use and all of it is layered in dry, cream-coloured mud. Over us is a canopy of pines that keep the sun out, and the ascent is still gradual.

After a half hour of climbing, Sumita pauses again. ‘I am feeling dizzy,’ she says.

‘Maybe we should let her sit down for a while, UD,’ I tell Ugyen, ‘she is not the kind to complain without reason.’

Before he can reply, Sumita closes her eyes, crumples. I rush in to break her fall, and we both go down in a tangle of limbs and down jackets by the outer edge of the uphill track.

In the long moments that follow, I have intense aural, visual and tactile clarity: my right forearm around Sumita registers her pulsating diaphragm; my right shoulder knows the entire weight of her head; I cannot see Sumita’s face, but I watch Ugyen standing before her, his eyes focussed on hers; I feel the jagged edge of a boulder thrusting itself against my left waist—I am pinned to it.

I have no thought, just the words of a familiar prayer going over and over in my mind.

A tourist rides by on a horse. ‘She isn’t feeling well? Put her on a horse,’ he says, disappearing round a bend above us in a flurry of dust.

Ugyen still watches Sumita's face. Then he takes out his cell phone from the pouch of his gho to call up Tandin. ‘I think you need to climb up,’ he says. ‘We may have to carry Sumita down to the car.’

This, then, is the end of our trek.

We wait for Tandin. Sumita stirs, sits up. ‘I think I feel better,’ she declares.

‘What do you wish to do? Shall we return?’ Ugyen asks her.

‘I think I will give it another shot,’ Sumita tells him. She then turns to me: ‘I am carrying the Diamox tablets. Do you think I can take one?’

It is a miracle she has them with her. We have had one dose last night, and that was meant to suffice against altitude sickness. ‘I saw the strip of tablets lying on our room table this morning,’ she would tell me later, ‘and thought I may as well put them in my bag.’

Sumita takes a Diamox. I have one, too, for good measure.

‘Let us set a smaller target,’ I say, ‘do just a third of the trek and reach the cafeteria. I know it offers a good view of Taktsang.’

We keep climbing. Ugyen plucks some Himalayan strawberries—Bentham’s Cornel—from a tree growing by the uphill path. With a skin like the lychee, though softer, the fruits are covered with dust.

‘Never mind the dust,’ Ugyen says, ‘these are good for acclimatisation. Eat up.’

We eat up. The pulp is soft and creamy like an over-ripe banana and full of tiny seeds. It has a bitter tang.

An elderly couple is climbing down.

‘Did you go all the way up?’ I ask.

‘No,’ replies the gentleman. ‘We were both getting a slight headache, so we have decided to return.’

It gets hotter as the day progresses, and when we finally reach the arch leading to the cafeteria, two hours into the trek, both of Ugyen’s arms are loaded with our down jackets and Sumita’s sling bag.

He still manages to look formal.

There are many Europeans at the cafeteria compound. A stocky man with a grey beard sits under a lawn umbrella gazing up at the sunlight cascading off the golden roofs of Taktsang. ‘I have always been a smoker,’ he says, ‘this tiger cannot go up there.’

-Excerpt from ‘Zanskar to Ziro:

No Stilettos in the Himalayas’ by Sohini Sen.

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com