Live

- Kiran Abbavaram's Hard Work Pays Off: Bunny Vasu Lauds Ka Team at Success Meet

- PM Modi’s welfare schemes transform rural lives in Bokaro, residents share gratitude

- We will ensure Bangladeshi infiltrators are removed from Jharkhand: BJP's Gourav Vallabh

- Hezbollah fires five rockets at central, northern Israel: sources

- HM Amit Shah, Rajnath Singh to address several rallies in Jharkhand tomorrow

- Will not waste single day in getting back what we lost, Omar Abdullah tells Assembly

- PM Modi visits Advani's residence to wish him on birthday, shares special moment

- Sun-Dried Cotton to Be Taken to CCI Purchase Centers, Avoid Middlemen - Collector

- Survey Process Requires Public Cooperation - Collector Badavath Santosh

- Distribution of Maize Seeds to Farmers at Agricultural Research Center

Just In

Personality cannot be entirely predictable but its basic pathways can be somewhat mapped. It, however, comes into its own when it meets a contrasting outlook(s), and these have to combine or clash – more so in literature. Anything with more than one principal character works on the interplay of differing personality types

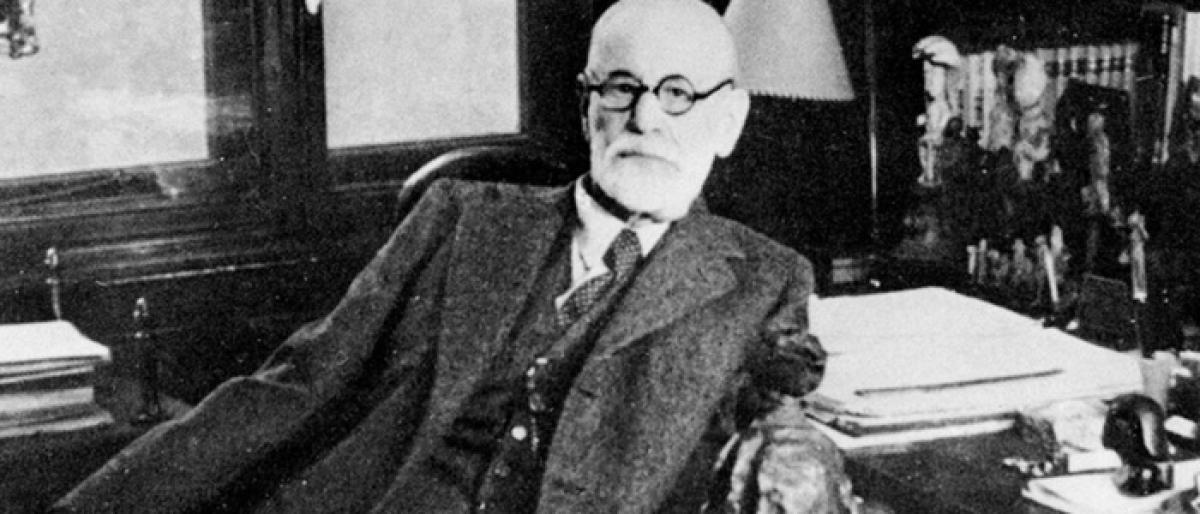

Personality cannot be entirely predictable but its basic pathways can be somewhat mapped. It, however, comes into its own when it meets a contrasting outlook(s), and these have to combine or clash – more so in literature. Anything with more than one principal character works on the interplay of differing personality types – ranging from two to five. The optimum is three – reflecting the famous Viennese psychologists conjecture of personality. While most of Sigmund Freud's theories have been discredited or replaced, they continue to make their presence felt in popular media. Among the most prevalent is his classification of the three constructs making up the psyche.

Outstripping the association of a passionate, impetuous, enthusiastic character matched with a more serene, controlled and observant counterpart (say Dr Watson/Sherlock Holmes or conversely, Tintin/Capt Haddock), the four-philosophy (cynical, realist, optimistic or apathetic/conflicted) or four-temperament (phlegmatic, sanguine, choleric and melancholic) ensemble or the five-man band (leader, lancer, smart guy, big guy and chick) is the Freudian Trio.

This trio of the Id, Ego and Superego is present in a wide range of literature from possibly the most famous trio of Russian brothers to the Boy (Wizard) who lived, a swordfight and intrigue story set in early 17th century France to the fantastic tale of a scientist and his aides taken (unwillingly) on a marvellous undersea tour, and the defining tale of Christmas to arguably the most famous space story – as seen on TV.

But what exactly are these three? Freud, in his ‘Beyond the Pleasure Principle’ (1920) and ‘The Ego and the Id’ (1923), postulated the individual psyche comprised these three parts, all developing at different stages in life and non-corporeal. Saul McLeod of the University of Manchester says that, at the simplest, they can be understood as the primitive and instinctual part of the mind that contains sexual and aggressive drives and hidden memories (Id), the moral conscience (Superego), and the part that mediates between desires of these two (Ego). Each has its unique features and they mix to form a whole, each part making its contribution to an individual's behaviour.

More simply, Id is completely unconscious and has no judgments or sense of morality and governs our basic instincts. For Superego, Freud, who was in a sexist time, envisaged it as a symbol of the strong father figure – emerging after a boy jettisoned the Oedipus complex and since women don't display this, their Superego is less developed. Ego, the referee, being realistic and rational, is the organised – and organising – part of the consciousness. While this is now commonly thought as a central mediator between the competing demands, Freud thought of it as more of a middleman, driven by the Id and confined by the Superego.

Freud originally used "das Es" (id), "das Uber-Ich" (superego) and "das Ich" (ego), or "the It", "the Over-I" and "the I", which while intelligible to German-speakers, had no evocative English equivalents, so his translator James Strachey coined them from Latin.

But where can we find them? One of the best examples is ‘Star Trek: The Original Series’ where the highly emotional Dr James ‘Bones' McCoy is Id, the supremely logical Spock is the Superego and Captain James T Kirk, who strikes the middle path, is the Ego.

Then Alexandre Dumas' ‘The Three Musketeers’ has the boastful and hedonistic Porthos (Id), the man of the world Aramis (Superego) and the quiet, noble Athos (Ego). Jules Verne's ‘20,000 Leagues Under the Sea’ is itself Freudian involving being dragged down to subterranean depths in a mysterious vessel, seeing frightening creatures, and so on. It’s not difficult to figure what impulsive Canadian harpooner Ned Land, calm aide Conseil, and mostly calm but sometimes upset Professor Aronnax represent.

In Fyodor Dostoyevsky's ‘The Brothers Karamazov’, the eldest Dmitri, with his boozing and wenching, the cold, clever and contemptuous Ivan and the youngest Alyosha, who is the only to have good relations with the others, are also obvious. Try to identify the Three Ghosts of Christmases that Scrooge sees in Charles Dickens' ‘A Christmas Carol’ too?

There is Harry Potter world – Harry, with his desire to save people at any cost, can be Id but with his constant mediation between Ron Weasley and Hermione Granger and his constant reliance on both, can be Ego. Ron, a balance between Harry's impulsiveness and Hermione's cautiousness can be the Ego or as fond of eating, oblivious to others' needs or states, can be Id. However, knowledgeable, respectful and rule-abiding Hermione is always the Superego.

Also, in the Marauders (save Peter Pettigrew) – the born rebel, highly emotional Sirius Black is Id, the less reckless but over-confident James Potter is Ego and studious and sensible Remus Lupin is Superego. Another popular fantasy series – Rick Riordan's Percy Jackson series – also display this, with again the wise woman protagonist (Annabeth Chase) the Superego, Percy, whose primary goal is to help his friends, the Id, and Grover Underwood the Ego. There are many more. Try to figure them out in the last multi-character book you read.

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com