Adherence, denunciation and inspiration

It is the great, not necessarily correct, but disruptive ideas about human nature and the world that evoke the most fervent reactions, both for and against. Some of the quite famous of these stem from a quartet of European thinkers, all born within seven decades in the 19th century, and having done most to shape the modern world – Charles Darwin, Karl Marx, Sigmund Freud, and Albert Einstein.

It is the great, not necessarily correct, but disruptive ideas about human nature and the world that evoke the most fervent reactions, both for and against. Some of the quite famous of these stem from a quartet of European thinkers, all born within seven decades in the 19th century, and having done most to shape the modern world – Charles Darwin, Karl Marx, Sigmund Freud, and Albert Einstein.

For all four helped to overthrow the existing worldview that humans were instinctively rational, that concord and harmony was the normal human condition, and that a "grand plan" underpinned the universe's functioning. But while Darwin's work spanned all living creatures, Marx's was about society, Einstein's looked at everything from the sub-atomic world to far-away universes, and Freud's work focussed on individuals – and their minds.

Since May 6 was his 162nd birth anniversary, let us take a look at Freud's main theories and what his adherents and critics – from renowned philosopher Bertrand Russell to poet WH Auden, surrealism's founder Andre Breton to modern pop icon Madonna, and even a best-selling author of suspense novels and Sanskrit scholar – made of them.

The founder of psychoanalysis, which stressed the techniques of free association and transference (of feelings), Freud sought to redefine sexuality to include its infantile forms – which led him to the "Oedipus complex" and dreams as symbols of wish fulfillment.

His method of clinically analysing symptoms led him to postulate that their origins lay in repressed memories and formed his theory of the unconscious – a concept dating back to Plato – and its psychical constructs of id, ego and super-ego. Then he conceived of "libido", an energy powering mental processes and responsible for erotic attachments, and a death drive, from which emanate compulsive repetition, aggression and neurotic guilt. Later, he sought to interpret religion and culture.

While all of our four thinkers have their staunch supporters and dedicated detractors, Freud, since he brought some uncomfortable views into contention, especially his emphasis on sex and an incestuous basis of identity formation, has more than a fair share – though often contradictory.

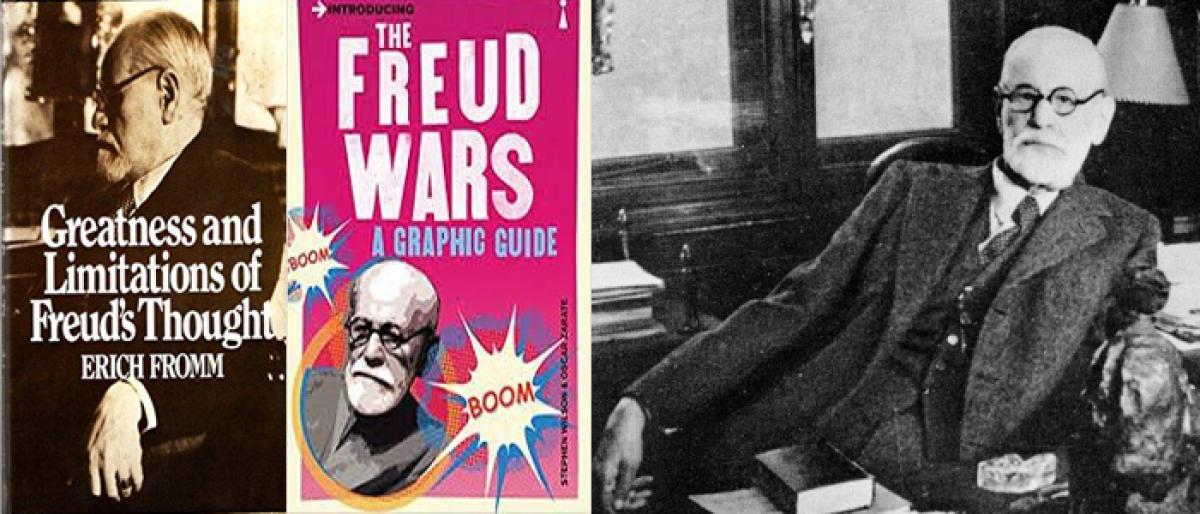

In ‘Introducing the Freud Wars’ (2002) by Stephen Wilson and Oscar Zarate (illustrator), psychiatrist Wilson, seeks an "uncompromising" investigation into the "chief accusations levelled against him (Freud) and the oppositions to his discoveries".

As Wilson tells us, Freud was charged with lying about his clinical practice, moral cowardice in his theorising, collusion in medical negligence, and overweening ambition, for drug addiction and "demonising children", and "responsible for delaying our recognition of infantile sexual abuse" as well as "the invention of false memories of infantile sexual abuse".

If this wasn't enough, he was "reproached for both unoriginality and myth-making, stating the obvious and mystifying us with the obscure" and was said to be guilty of encouraging both libertinism and puritanism, and misogyny and homophobia, and even planning to murder a close friend he later fell out with.

However, Wilson undertakes a balanced approach as he deals with these charges as well as others to show where Freud was on the right track, where he came to know he was wrong and admitted it, and where he was wrong, in light of further research.

One of the areas where Freud acknowledged he had been wrong was his seduction theory, attributing adult neurosis to childhood sexual abuse before later discerning they were "fantasies". However, Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson, Sanskrit scholar-turned-psychoanalyst and newly-appointed Secretary of the Freud Archives, alleged that Freud abandoned this for personal reasons, and "began a trend away from the real world", which accounted for "the present-day sterility of psychoanalysis throughout the world".

Masson was soon sacked by the trustees, but did his charge have any basis? Journalist Janet Malcolm tells us in ‘In the Freud Archives’ (1984), which also draws in Freud's daughter Anna, veteran psychoanalyst KR Eissler, and Peter Swales, a former assistant to the Rolling Stones. It also deals with legacies, posthumous reputations and the human tendency to believe only they can properly explain someone's thought.

And then, Freud figures widely in popular culture. While Breton lauded him for studying dreams, Auden's ‘In Memory of Sigmund Freud’ (1940), said: "He wasn't clever at all: he merely told/the unhappy Present to recite the Past..." and "if he succeeded, why, the Generalised Life/would become impossible, the monolith/of State be broken..." and that "If often he was wrong and at times absurd/To us he is no more a person/Now but a climate of opinion", and Madonna sang "Sigmund Freud. Analyse this! Analyse this! Analyse this-this-this!" in James Bond's ‘Die Another Day’.

A better estimation is made by psychiatrist/psychoanalyst Erich Fromm, who in ‘The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness’ (1977), holds him "one of the last representatives of Enlightenment philosophy", who genuine believed in reason as a human strength.

His ‘Sigmund Freud's Mission: An Analysis of His Personality and Influence’ (1959) and ‘Greatness and Limitation of Freud's Thought’ (1979) offer more light on the discrepancies between early and later theories.

Then Richard Panek's ‘The Invisible Century’ (2004) compares how Freud and Einstein rejected the 19th-century scientific paradigm that accurate measurements of physical aspects would yield the universe's secrets. There is more to Freud than preconceived notions – we just need to dig more and wide. He would have approved!