Live

- Pakistan Protests: PTI Supporters March Towards Islamabad, Demanding Imran Khan's Release

- Additional Collector Conducts Surprise Visit to Boys' Hostel in Wanaparthy

- Punjab hikes maximum state-agreed price for sugarcane, highest in country

- Centre okays PAN 2.0 project worth Rs 1,435 crore to transform taxpayer registration

- Punjab minister opens development projects of Rs 120 crore in Ludhiana

- Cabinet approves Atal Innovation Mission 2.0 with Rs 2,750 crore outlay

- Centre okays Rs 3,689cr investment for 2 hydro electric projects in Arunachal

- IPL 2025 Auction: 13-year-old Vaibhav Suryavanshi becomes youngest player to be signed in tournament's history

- About 62 lakh foreign tourists arrived in India in 8 months this year: Govt

- IPL 2025 Auction: Gujarat bag Sherfane Rutherford for Rs 2.60 cr; Kolkata grab Manish Pandey for Rs 75 lakh

Just In

\"It will be sad to see Cassini go on Friday, especially as the instrument we built is still working perfectly,\" said Stanley Cowley, professor of solar planetary physics at the University of Leicester.

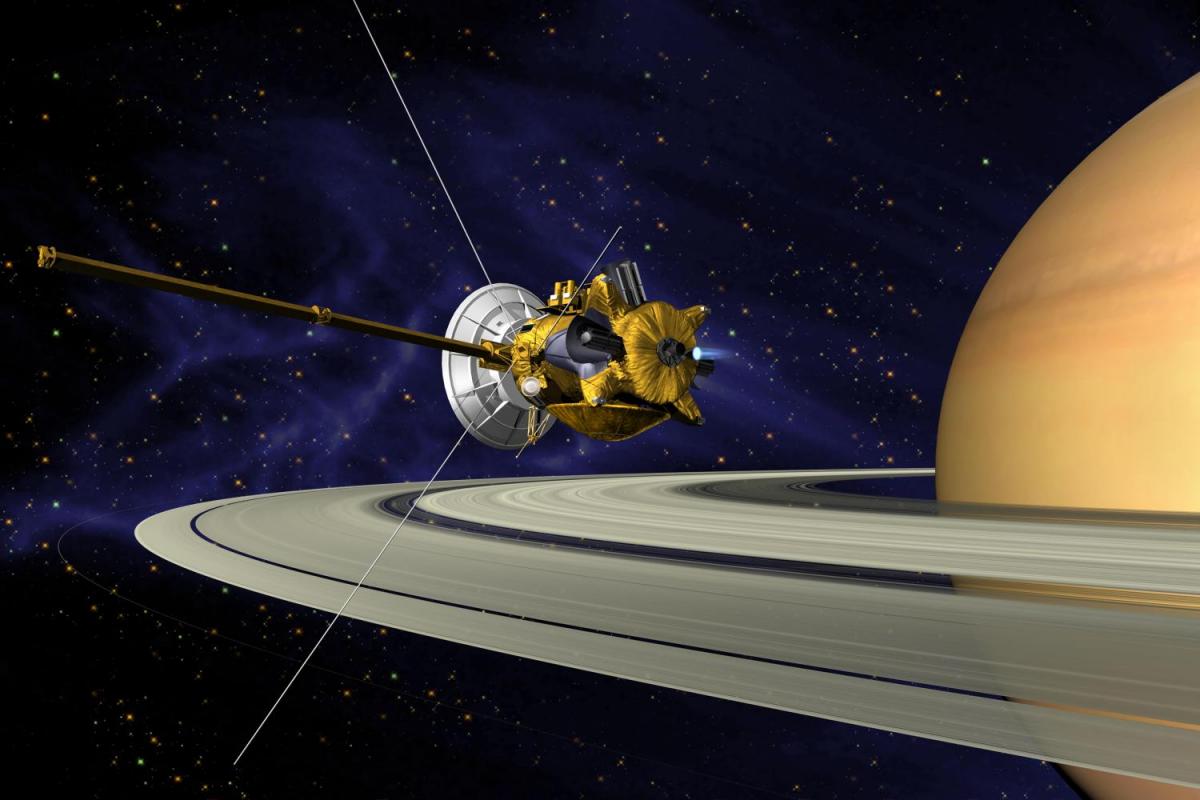

For more than a decade, NASA's Cassini spacecraft at Saturn took "a magnifying glass" to the enchanting planet, its moons and rings.Cassini revealed wet, exotic worlds that might harbor life: the moons Enceladus and Titan. It unveiled moonlets embedded in the rings. It also gave us front-row seats to Saturn's changing seasons and a storm so vast that it encircled the planet.

"We've had an incredible 13-year journey around Saturn, returning data like a giant firehose, just flooding us with data," project scientist Linda Spilker said this week from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. "Almost like we've taken a magnifying glass to the planet and the rings."

Cassini was expected to send back new details about Saturn's atmosphere right up until its blazing finale on Friday. Its delicate thrusters no match for the thickening atmosphere, the spacecraft was destined to tumble out of control during its rapid plunge and burn up like a meteor in Saturn's sky.

Here is a brief look back at Cassini and why this mission is coming to an end:

$3.9 billion Saturn spacecraft

Cassini, an international project that cost $3.9 billion and included scientists from 27 nations, rocketed from Cape Canaveral, Florida, on October 15, 1997, carrying with it the European Huygens lander. The spacecraft arrived at Saturn in 2004. Six months later, Huygens detached from Cassini and successfully parachuted onto the giant moon Titan. Cassini remained in orbit around Saturn, the only spacecraft to ever circle the planet. Last April, NASA put Cassini on an ever-descending series of final orbits, leading to Friday's swan dive. Better that, they figured, than Cassini accidentally colliding with a moon that might harbor life and contaminating it.

Death plunge

Cassini has run out of rocket fuel as expected after a journey of some 4.9 billion miles (7.9 billion kilometers).Its death plunge into the ringed gas giant -- the furthest planet visible from Earth with the naked eye -- is scheduled for shortly after the spacecraft's final contact with Earth at 7:55am (11:55 GMT).

Cassini's well-planned demise is a way of preventing any damage to Saturn's ocean-bearing moons Titan and Enceladus, which scientists want to keep pristine for future exploration because they may contain some form of life.

"It will be sad to see Cassini go on Friday, especially as the instrument we built is still working perfectly," said Stanley Cowley, professor of solar planetary physics at the University of Leicester.

Spacecraft

Traveling too far from the sun to reap its energy, Cassini used plutonium for electrical power to feed its science instruments. Its separate, main fuel tank, however, was getting low when NASA put the spacecraft on the no-turning-back Grand Finale. The mission already had achieved great success, and despite the chance of pounding Cassini with ring debris, flight controllers directed the spacecraft into the narrow gap between the rings and Saturn's cloud tops. Cassini successfully sailed through the gap 22 times, providing ever better close-ups of Saturn.

Rings

Cassini discovered swarms of moonlets in Saturn's rings, including one called Peggy that made the short list for final picture-taking. Scientists wanted one last look to see if Peggy had broken free of its ring. Data from the spacecraft indicate Saturn's rings — which consist of icy bits ranging in size from dust to mountains — may be on the less massive side. That would make them relatively young compared with Saturn; perhaps a moon or comet came too close to Saturn and broke apart, forming the rings 100 million years ago. Or perhaps multiple such collisions occurred. On the flip side, more massive rings would suggest they originated around the same time as Saturn, more than 4 billion years ago.

Moons

Saturn has 62 known moons, including six discovered by Cassini. The biggest, by far, is the first one discovered way back in the 1655: Titan, which slightly outdoes Mercury. Its lakes hold liquid methane, which could hold some new, exotic form of life. Little moon Enceladus is believed to have a global underground ocean that could be sloshing with life more as we know it. Incredibly, geysers of water vapor and ice shoot out of cracks in Enceladus' south pole. Project scientist Linda Spilker said if she could change one thing about Cassini, it would have been to add life-detecting sensors to sample these plumes. But no one knew about the geysers until Cassini arrived on the scene.

Next up

Scientists would love to return to Enceladus or Titan to search for any potential life. Nothing is firmly on the books right now. But there are proposals to go back, submitted under NASA's New Frontiers program. So stay tuned.

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com